In a major win for advocates for unhoused people and pedestrians alike, the Supreme Court has declined to hear a case that some feared would enable cities to ban residents from lingering in medians on dangerous roadways, rather than redesigning those roads to better protect walkers.

Local officials in Oklahoma City have officially exhausted the appeals process after the High Court denied their petition to review a lower court's decision that declared the community's controversial median safety law unconstitutional under the First Amendment. The Supreme Court gave no explanation for the denial.

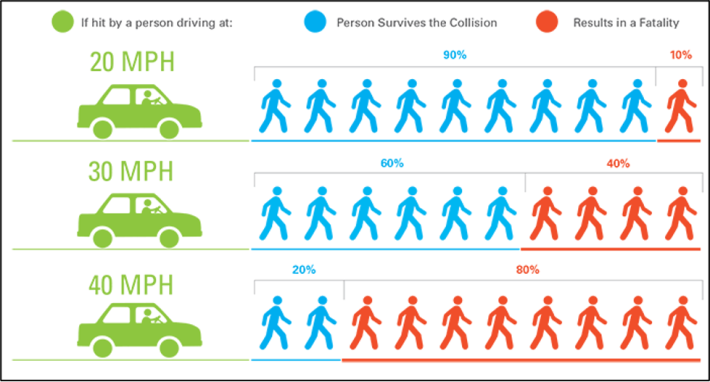

That law prohibited anyone from standing, sitting, or loitering on pedestrian medians located in roads with speed limits of more than 40 miles per hour — a category which includes roughly 400 of the city's estimated 500 medians in all. The city claimed was the only way to protect its pedestrians on region's high-speed roads, citing the fact that walkers struck at 40 miles per hour die roughly 80 percent of the time. They also pointed to the 39,833 car crashes that occurred on OKC roads between 2012 and 2017, though notably, the city couldn't produce evidence that any walkers had actually been injured while standing on a median prior to the law.

But the American Civil Liberties Union, which filed the original lawsuit, said the ordinance had "nothing to do with traffic safety," and was clearly intended to curb panhandling and further criminalize unhoused people in the public realm.

The Sooner State capital had successfully defended the law in an Oklahoma City court before the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously struck it down. If SCOTUS had taken up the case, it may have been the only time pedestrian safety has ever been discussed at the highest level of the judiciary, at least in in recent memory.

Perhaps most damning to the city's safety claims were the insidious origins of the ordinance itself. When it was first introduced, city councilwoman Meg Sayler, who helped introduce the reform, publicly called it an anti-panhandling measure and stated that it was written in response to constituents' "complaints," before listing several organizations that connect unhoused Oklahomans with the resources they need, without the need to solicit drivers in the middle of dangerous, high-speed roads.

But many street safety advocates argue that anti-panhandling laws themselves endanger unhoused people on our roadways, in part because they invite interactions with law enforcement that can easily turn violent — while doing nothing whatsoever to address the root causes of homelessness. Unhoused people in America are disproportionately Black, and almost uniformly rank among the poorest and most medically vulnerable residents of our cities.

Oklahoma City officials quickly recognized that the law wouldn't stand a chance if the word "panhandling" got anywhere near it – especially after the higher courts got involved. Just six months before the ordinance made it onto the local books, another Supreme Court decision about a city's right to restrict the content of church signage unleashed a surprising wave of cases across the country aimed at striking down anti-panhandling ordinances that curbed the rights of unhoused people to hold signs asking for money or food.

But by the time the OKC law was official, it had been given a dubious makeover as a pedestrian safety measure — which ironically meant even more city residents' rights would be swept up by the ban. The plaintiffs that challenged it included a broad swath of Oklahomans, including not just individual unhoused people who solicit cash donations on medians, but also vendors of the Curbside Chronicle, a local street newspaper, as well as the local firefighters union, who regularly hold drive-up fundraisers for the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Private citizens pointed out that simply standing in a median with a protest sign would be a violation of the rule, too — which they argued was a clear infringement on political speech, the most protected type under the First Amendment, albeit not in all contexts.

"We don’t have an absolute right to free speech in America, because there's balance between the government's interest and the public's rights," said Sheila Foster, a professor of urban law and policy at Georgetown. "The city is saying, 'Well, the ordinance isn't really banning free speech; it's placing what we call a "permissible time, place and manner" restriction on free speech, in this case speech occurring in the unsafe environment [of the roadway].' The issue here is not whether someone has an absolute right to be on the street, but what is the government’s burden when it tries to select who gets to be there, and for how long."

But some questioned whether that limiting free speech of Oklahomans was even a necessity in this case, given the other option available to the city: simply limiting drivers' speeds.

"Clearly, keeping pedestrians safe should be a significant government interest," said Ken Stahl, a law professor at Chapman University. "That's not in question. What is in question is: are there less restrictive means of accomplishing that goal than banning pedestrians from medians? Had the city tried those other, less-restrictive means first? This is just me spitballing here, but could you have put plastic bollards along the median? Could you have changed the signal timing? Could you have calmed traffic along the road?"

After an initial defeat at the district level, a higher court ultimately agreed. Last August, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals found the OKC law violated the First Amendment — and also noted that the safety studies the city cited in defense of the law did "not propose limiting or banning pedestrian presence in any manner," recommending increased pedestrian infrastructure and education campaigns for drivers instead.

But while Oklahoma City's defeat may be final, some think it's high time we take our deadly roadway safety norms to court – or even enshrine the right to safe mobility into federal law, just as other countries have already done.

Last year, Mexico amended its constitution to enshrine its citizens's "right to mobility under conditions of safety, accessibility, efficiency, sustainability, quality, inclusion and equality"; the elements of the U.S. constitution that deal with freedom of movement, by contrast, are far less specific, which makes it hard to argue in a court of law that pedestrians' rights to safe mobility is infringed by drivers' rights to drive dangerously fast nearly everywhere.

"The very nature of American streets is very conflicted in American law," added Stahl. "On the one hand, the courts have been very clear that the streets are a public forum for speech and expression. On the other hand, we have a status quo that tends to think of city streets as being primarily about moving cars as quickly as possible. You could view that as a part of the larger move towards privatizing public spaces; the streets are technically public, but we’ve basically given them over to private automobiles. So when people try to exercise the right to free speech in the street realm, you hear people say, 'Let’s run them down.'"