We're finally getting hard data on exactly how many cars have vanished off the roads in the wake of COVID-19 — and what we're learning suggests that we need even more drastic action to stop the spread of the virus and keep vulnerable road users safe.

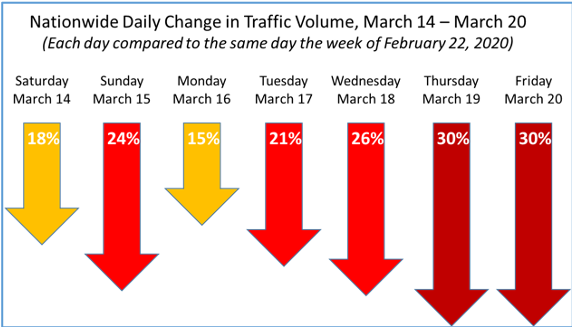

New data reveals that nationwide car traffic dropped a shocking 30 percent at the end of last week compared to the same day of the week as the month prior, according to traffic data firm INRIX.

But what might be even more shocking is that traffic didn't crater even further. By Friday, March 20, major cities across America were under strict lockdown orders — but many other towns, especially in smaller communities, were not. Even Seattle, which was an early epicenter of the virus, only fell under a mandatory state-wide stay at home order on the evening of Monday, March 23.

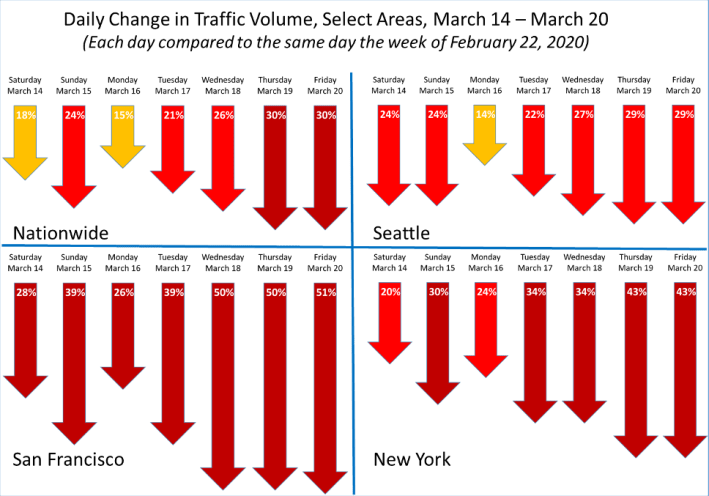

The reluctance to take urgent action shows in Seattle's traffic numbers. The Emerald City's drop in traffic volume was actually lower than the national average through much of last week — and by the end of the week it was way lower than San Francisco and New York, which were also hit hard by the virus.

Advocates believe that when a city shows a less-aggressive drop in vehicle miles traveled, that's a clear sign that the local government needs to take more aggressive steps to keep non-essential travel to a minimum.

And before anyone argues that maybe all those folks out driving are members of essential services professions: nope, they're probably not. Roughly 1.8 percent of Americans work in hospitals, 0.7 percent work in grocery stores, and possibly even fewer work in food production, fire and police response, and other essential services — and of course, not all of these people drive cars. But no city in the US has demonstrated a greater than 51 percent drop in VMT — which suggests a lot of people are still going out and potentially spreading the virus who don't strictly have to leave their homes to keep society functioning in this unprecedented time.

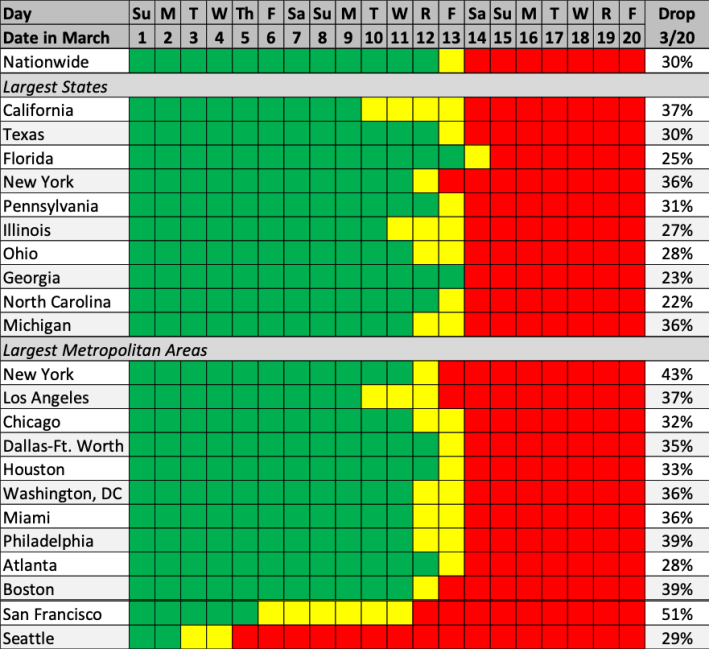

But at least things are trending in the right direction. Here's a broader look at how the largest states and cities traffic patterns have looked since March 1, both before and after their respective state and local governments began to respond to the outbreak. Seattle looks a little better off here; they didn't cut traffic by quite as much as other major metros, but at least they started early:

Of course, to some degree, these charts only quantify something we already know: that car travel is in free fall almost everywhere. And they don't tell us much about the consequences of this sudden VMT drop — especially for vulnerable road users.

All around the world, walkers are observing that the drivers who are still out there on our newly uncongested roads are moving much faster — and posing a more deadly danger to road users, since driver speed is among the most reliable predictors of pedestrian mortality in a collision. In New York City, speed cameras are still spitting out roughly the same number of tickets, despite the falloff in driving; ditto England, which is also seeing an uptick in distracted and drunk driving; same deal in Los Angeles.

And the reason why is simple: more car traffic itself is traffic-calming, even if it's the most destructive form of traffic-calming available to us. Now that reports are confirming that car-congestion has dropped precipitously, it's time our leaders recognize two things: 1) that drop in vehicle traffic is a good thing, and we need much more of it both to stop the spread of COVID-19 and keep pedestrians safe, and 2) that we need to take aggressive steps to slow the cars that are still on the road, so we can protect the skyrocketing number of people who are out walking and biking.

We'll have more on how, exactly, cities can do that shortly. But for now, let's take a moment to marvel at just how much of an impact our inadvertent national experiment in VMT reduction is truly having.