Imagine a world where your local planning department leaders know exactly how many people are driving, walking, biking and taking transit on every single street in your city, at all times.

They know the moment when a car crash happens. They know how many seats are occupied on every train or bus — and know the moment when those modes are so full that riders get turned away. They know how many people are walking down a busy street without a sidewalk. They know the routes of every commute — whether to the downtown core or to some new job center that just sprang up, and, from that information, could follow up and determine how many of those drivers would be perfectly happy to take a bus if they just had a convenient stop.

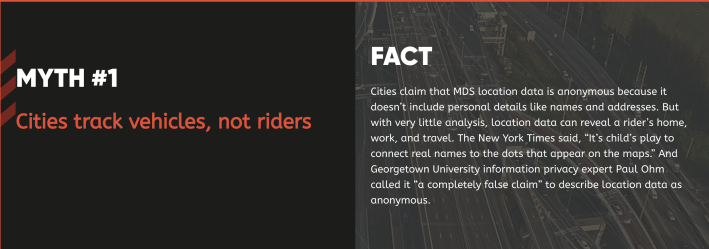

Sounds great, right? But there's more: The data is anonymous, of course, but a supercomputer and a census map overlay would make it pretty easy to put a name to nearly every faceless data point on the map.

So is all this data a nightmare? Or an incredible opportunity to start using all that data to build a transportation system that really works?

Is Big Brother watching?

It's a question that's at the heart of a new debate about the role of big data in transportation — and if two opposing groups succeed, it will soon be on the lips of everyone who cares about the future of our streets.

The first is Citizens Against Rider Surveillance, a diverse coalition which was borne out of an ongoing dispute between Uber and the Los Angeles Department of Transportation. The app-based taxi giant and the city agency are currently embroiled in a lawsuit, with Uber alleging that the DOT overstepped its bounds when it began requiring micromobility companies, like Uber's own Jump, to supply real-time trip data directly to the city in 2018.

The city argues that it needs to know where and when citizens are using new modes so it can better build infrastructure to keep riders safe and effectively regulate the growing industry. Officials also point out that by not demanding location data from Uber's car drivers from the start, they lost out on a huge opportunity to understand and regulate the impact of ride-hailing apps on their community — and their streets have been clogged with dangerous car traffic ever since.

While the lawyers fight it out in the courts, the Citizens Against Rider Surveillance are fighting in the court of public opinion. With the support of Uber and a raft of privacy rights activism groups, the coalition has been churning out op-eds urging citizens to imagine the nightmare scenarios that could come true if the government gets more data about citizens' movements. Ransomware attacks on city databases by dangerous hackers is a common theme; so are images of a future where Immigration Customs and Enforcement officers can easily burst through an undocumented person's door and drag her to a detention center, simply because they tracked her Jump scooter ride home.

"Location information can be deeply revealing and provide a window into a person's private life," said Keeley Christensen, a spokesperson for the coalition. "Yet city governments want to have access to this data with little to no transparency or accountability."

But the Citizens' Against Rider Surveillance's unfortunate acronym — CARS — might be a telling one.

Skeptics argue that the reason Uber doesn't want to turn over data to cities is that the company's ultimate goal is to monopolize the way Americans get around — and if the company handed over valuable info on where people are going, cities could build convenient transit lines that would steal the passengers out of its cars instead. They also point out that government officials including ICE officers can already subpoena location services data from from cell phones, and that Uber itself has been the target of hackers just like government servers.

And more to the point, cities already have a way to access to rider data — whether they're in the back of an Uber or the seat of a bike. It's just that, right now, they have to pay for it, rather than getting it from mobility companies for free.

A better birds-eye view of how people get around

Streetlight Data is the other group making big waves in the conversation about using big data for mobility. But it's not an advocacy group: it's a private company that provides cities, companies and organizations with software licenses that let them see how, when and where their citizens and customers are traveling — at least within the bounds of an anonymized GIS map.

Sourced largely from location services data that citizens voluntarily provide to private companies from their smart phones and GPS devices — if you think you didn't say yes to that, sorry, but you probably did — Streetlight already has customers in the lower 48 states, and it advises almost 3,000 projects every month. And those projects include helping the a locality in California figure out the best place to put electric vehicle charging stations and helping the Pro Football Hall of Fame craft a parking plan for visitors to the pigskin-shaped shrine in Canton, Ohio.

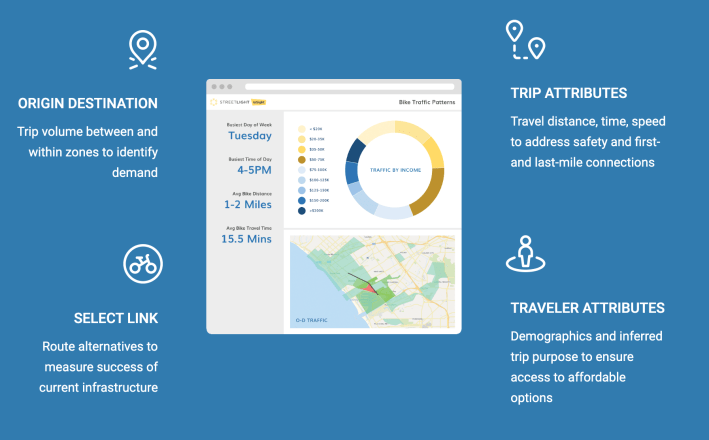

If those all sound like the same kind of tired old transportation projects that have reinforced car supremacy for generations, they are. But Streetlight argues that its tech has applications in the sustainable transportation world, too — and it can give cities access to a much wider set of data about walking, biking and transit at a cheaper price point than ever before.

"Whatever mode we're talking about, the transportation sector is spending trillions of dollars to get not a whole lot of information," said Martin Morzynski, a Streetlight vice president. "And most of those dollars are being spent on sensors that are scattered across our roads, and surveys being sent to peoples' homes. It doesn't provide anything near a complete picture of how people actually get around."

When it comes to measuring sustainable transportation patterns, the return on public investment is often even lower — if the public bothers to invest at all. In an era of virtually non-existent funding for bike/walk infrastructure, automatic pedestrian-counting cameras like the ones that dot Times Square are out of reach for most communities; instead, the most common technologies used in pedestrian counts are thumb counters, paper, and pens, often wielded by volunteers for an under-resourced local bike/ped nonprofit.

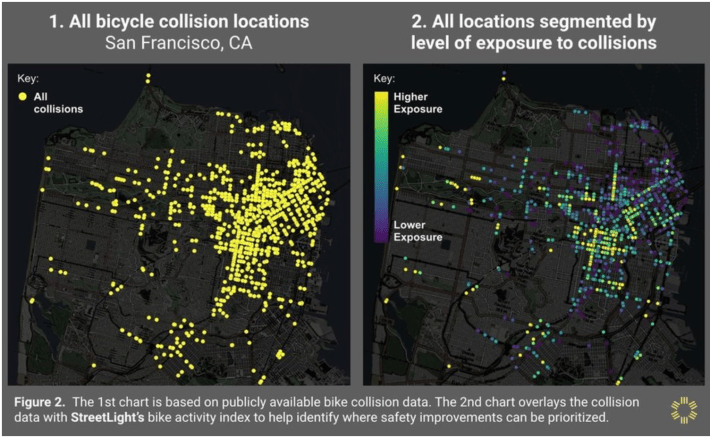

But when we start looking at the Strava and Google Maps location data that citizens are already beeping from their pockets without even realizing it, some fascinating patterns emerge. Last October, Streetlight released a map of the most-biked streets in San Francisco according to its tech, then overlaid that map with the city's bike collision data to identify the first places SF should build bike lanes and traffic-calming interventions.

When asked about whether people who own smartphones are really a representative cross-section of San Francisco, Morzynski emphasizes that 81 percent of Americans have a tiny computer in his or her pocket right now — and in the moneyed Bay area in particular, "even unhoused people often have iPhones." And when Streetlight data on Average Annual Daily Traffic is validated against sensors, surveys, license plates and more, its tech turns out to be more accurate than traffic studies cities are paying out the nose for every year.

As for privacy concerns, the company's customers can use StreetLight's InSight feature to determine broad demographic trends related to travel patterns while keeping individual road users identities' anonymous.. And in many ways, that may be a good thing: few transit agencies are able to demographically segment their traffic counts, so there's scant information around how the transportation network is serving road users of different races, income groups and education levels. By overlaying census data onto its maps, Streetlight might be able to help cities figure out where they're failing their most vulnerable users so they can do better. And there are built-in safeguards against clients using Streetlight metrics to identify individuals beyond these broad categories.

The question, skeptics say, is whether those safeguards will be enough.

Unanswered questions

Whether it lands in the hands of a government, a VC-funded tech taxi company, or a private analytics firm, Big Data is poised to arrive in our transportation planning process in a big way. The question is: where will it take us?

After all, a traffic study is only as good as the person who analyzes it — and even a perfect, real-time picture of our mobility landscape can be misused by someone with a pro-car bias. As Strong Towns' Daniel Herriges pointed out recently, a traffic study that notes a rising number of cars on a given road can easily become a traffic projection that car travel will increase. And that can all too easily turn into a recommendation to widen the road, even if that will only cultivate more induced demand, starting the vicious cycle all over again. Or as Herriges puts it:

By extrapolating mileage trends into the future, we are extrapolating the policies that caused those trends—like massive highway building—into the future as well, and we’re subtly ruling out the option of changing those policies. We’re saying, "New freeways will be necessary to accommodate all the traffic generated by our new freeways." Chicken, meet egg.

It's not a foregone conclusion that thoughtful transportations leader could look at a Big Data-generated map that shows no one's cycling in their city and decide that's a great reason to invest in protected bike lanes. But it's also not a foregone conclusion that someday, this data could be used for purposes that won't make our streets safer — like sending a cyclist a ticket in the mail for failing to use that bike lane, even if it sucks.

Perhaps the real question we should be asking is this: will our transportation culture evolve as quickly as our data capacity, so that we can make good use of all this new tech? The answer, of course, is up to all of us.