Last week, we explored the emerging idea that the Vision Zero approach to ending roadway fatalities is missing a pillar: policies that directly reduce car travel on our roads — and not just by providing drivers optional transportation alternatives. Today, we're laying out the tools some cities are already using to subtract motor vehicles from their streets — and a few they might consider putting into practice in tandem with increases to sustainable transportation.

1. Toll roads

Let's start with the most prevalent car-reducing mechanism on American streets: the humble toll box. After all, who hasn’t paid a few bucks to drive on the turnpike now and then? Expanding toll roads into our cities is a simple and effective way to make drivers think twice about hopping behind the wheel when a greener transportation option is available — and help bring the real costs of our auto-centric road network into better alignment with what drivers pay to use it. (Reminder: they only pay about 51 percent of road spending now.)

Yes, putting tolls on roads disproportionately burdens poor drivers. But so does every other way we fund roads — and toll roads may be one of the only ways to collect the revenue we need to build lower-income residents a sustainable alternative to driving, which would save everyone money in the long run.

2. Congestion pricing

Tolling highly traveled roads is a great first step — but tolling roads more when there’s the high demand to drive on them is even better. Congestion pricing, otherwise known as “variable demand pricing,” is an innovative way to get drivers to pay the actual cost of the asphalt they use, and encourages them to skip a clogged commute in a single occupancy vehicle if they can.

New York City is poised to become the first in the U.S. to try congestion pricing (if the feds ever let Gotham out of environmental review purgatory). If you’re a resident of the Empire State, it might be a good moment to call U.S. DOT Secretary Elaine Chao and urge her to get this project off the ground — so the rest of the country can learn from NY's bold step.

3. Surge pricing for parking

Variable demand pricing isn't just for roadways. Jacking up the price of parking when there’s more demand for spaces can be a simple way to discourage unnecessary car trips — and if you’ve ever taken the bus to a major league baseball game so you don't have to pay extortionate lot fees to park near the stadium, you already know this works.

Why shouldn’t your city get a share of the profits when there's big demand for parking? It should — and we should invest every penny of that money into alternative transportation that doesn't require parking at all.

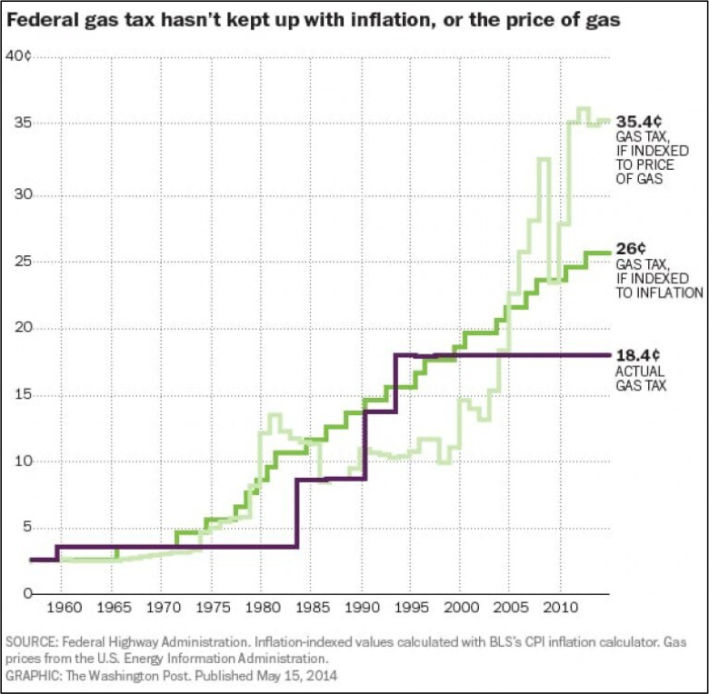

4. Increase gas prices

There’s a well-documented relationship between increases in gas prices and decreases in driving — and unfortunately, the opposite is true, too. And though it’s hard to influence oil prices directly, the U.S. is long overdue to increase its federal gas tax, which hasn’t been raised since 1993. Ending oil company subsidies probably couldn’t hurt, either.

No matter how you slice it, studies show that a 10-percent increase in gasoline prices results in between 2.2 and 6 percent decreases in pedestrian deaths. A few extra cents at the pump is a small price to pay to save lives.

5. Vehicle-miles-traveled taxes

What might be even better than increasing gas taxes is to get rid of them altogether and replace them with something better. After all, when your road network gets more funding from a fuel inefficient vehicle than a hybrid or an electric car, you give lawmakers a perverse incentive not to clean up the vehicle fleet. Wouldn’t it be better if our transportation system rewarded people who drove less — and simply scaled down our road spending as car-focused roads empty out and revenue drops?

It’s called a “vehicle miles traveled” tax, or a "pay-by-mile" tax, and it gets assessed at the end of the year based on a mileage reader on your car. Oregon is already piloting it. Maybe your state should be next.

6. Distance-based vehicle insurance

Another simple way to reward drivers for skipping the occasional ride is to cut their insurance rates every time they leave the whip in the garage. It makes a ton of sense for insurance companies, too: a car you leave at home, after all, is literally never going to be found at fault in a crash that triggers an expensive pay-out.

There are already pay-per-mile insurers out there — this isn’t #SponCon, but we’ve heard pretty good things about Metromile. Every major insurance company should add the option for customers to save by engaging in the safest driving behavior of all: leaving their car at home.

7. Car-free streets

Before anyone starts clutching his or her pearls: #BanCars doesn’t have to mean #BanCarsEverywhereForeverRightNow. And recent experiments in closing sections of the city to private vehicles have already saved lives in New York and San Francisco.

The thing about car bans is that American cities have a ton of them already — even if they don’t think of them that way. The Seattle neighborhood group Queen Anne Greenways had a great Twitter thread the other day about the many car-free spaces Americans already embrace, from indoor shopping malls to school campuses to Disney World. Banning cars on strategic stretches can be a surprisingly pain-free way to show skeptical drivers how much easier it is to get around when you don’t prioritize auto travel over everything else — even if that seems like a paradox to them today.

8. License plate lotteries

This is more extreme but it isn’t science fiction. In Beijing, private vehicle ownership is actually capped by a vehicle permit lottery, which limits how many new cars can legally be sold and put on the road. Residents have just a one-in-2,000 chance of winning the lottery, which happens bimonthly; if you don’t win, your transportation needs will still be covered, thanks to the city’s excellent public transit network.

The Chinese government is not exactly forthcoming with their roadway stats, but one report indicates that Beijing's roadway mortality rates decreased 34 percent between 2014 and 2016. The license lottery has been in effect since 2011, so it’s a pretty good guess that reducing cars on the road had something to do with that astonishing dip.

9. Road space rationing

Again: not sci-fi. In dozens of major global metros, the solution to keeping cars off the road is elegant: they only allow drivers to take their vehicles out on specified times or days.

Here’s how it typically works: every day, drivers whose license plates end with certain numbers are banned from using the roadways outright, or they're limited to driving during non-peak hours, or only outside of highly congested downtowns. Drivers who violate the ban get ticketed; drivers who don’t get to enjoy less congested streets on their designated driving days; sustainable transportation users, meanwhile, get to move freely along streets with fewer dangerous vehicles threatening their lives.

It’s a complicated system that requires a lot of communication, especially when cities adjust their rations dynamically, as some do. But still: isn’t all that bureaucracy worth it if we can save even a single life?

10. Cold, hard cash

Hey, we collectively subsidize driving in all kinds of ways, from free parking to debt-fueled car infrastructure to government grants to oil companies and auto manufacturers. Is it really so outrageous to give a cyclist or a bus passenger a few bucks a month, simply for choosing a mode that doesn’t cost carry outrageous costs to society?

Individual companies already pay employees for not taking advantage of their at-work parking benefit; Todd Litman has some compelling research that suggests these programs saved CEOs money in the long run, compared to what those organizations previously spent on real estate and asphalt maintenance to store their employees’ cars all day. Why shouldn’t members of the public see a benefit for saving departments of transportation dollars when we pick cleaner ways to get around? And more importantly, why should we be so shy about putting a little financial hurt on people who insist on driving, even if we provide them a financial incentive not to?

[Editor's note: This isn’t an exhaustive list of VMT-reducing strategies — and we need even more of them if we want to get dangerous cars off our roads as we build better ways to get around. Add yours to the comments section, or @ us on Twitter.]