Over the past 50 years, L.A. has grown up. Between 1960 and 2014, the city added more than 900,000 residents on land that was already at least partially developed, outpacing every other city in the country. And that growth has been relatively continuous: Since 1990, those same neighborhoods added 250,000 people. Moreover, L.A. has centralized over that time, gaining more than 120,000 people within three miles of City Hall.

That’s a big deal because, as UCLA Professor Ethan Elkind noted to me, “transit is all about the land use around it.” For trains and buses to be the workhorse of a region's transportation system, transit stops have to be integrated within compact, walkable neighborhoods.

L.A. is becoming more compact, but its built environment is still more conducive to driving than to walking and transit. Even as the region's rail network grows, too many stations remain engulfed by single-family housing and park-and-ride lots, development patterns that make it harder to walk to transit. And the less people walk to transit, the less they ride. To make the most of its investments in trains and buses, the L.A. region has to do a better job aligning land use and transit.

A vast built-up region, without much of a center

The typical urban development pattern is known as the monocentric city. In the monocentric city, the tallest buildings, biggest clusters of jobs, and highest concentrations of residents are located downtown.

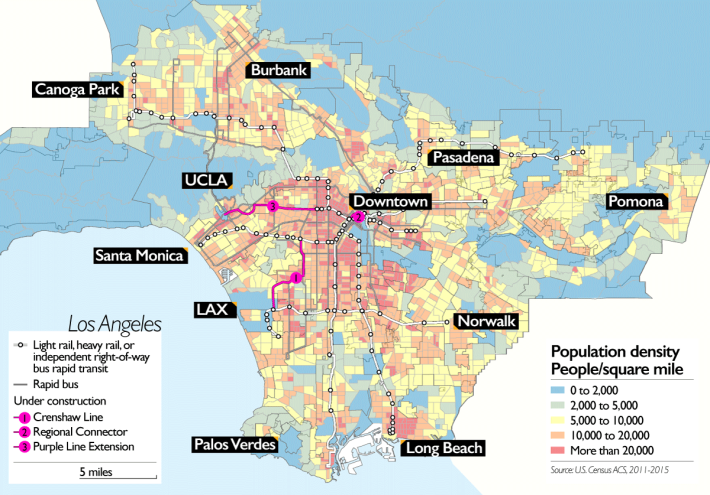

Los Angeles isn’t like that. It has a downtown, but L.A. County’s development is spread out almost evenly across a tapestry of neighborhoods -- and many of them are relatively dense.

Consider the following map of population densities. Neighborhoods of more than 10,000 people per square mile are arrayed from Long Beach to Burbank, from Santa Monica to Pomona.

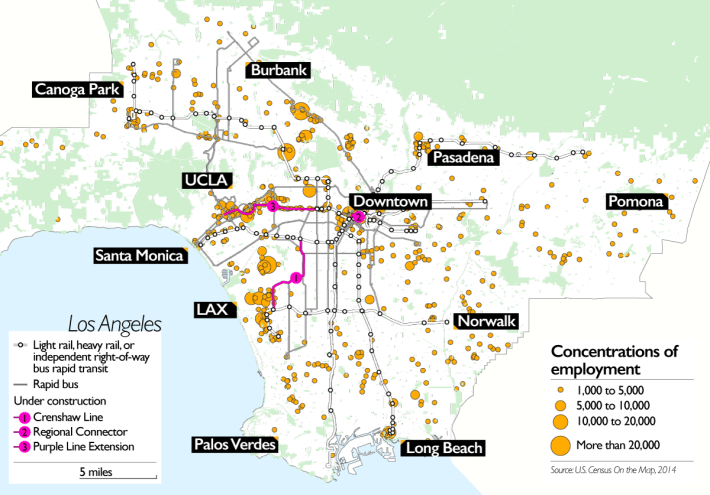

Similarly, jobs in L.A. County are clustered in many nodes, not just one. While employment tends to be concentrated in areas served by rail and BRT, such as downtown and Long Beach, other parts of the region are left out -- and will still be left out even after transit projects under construction wrap up.

This distribution of jobs and people distinguishes L.A. from other American cities. In some ways it works against transit, because ridership is usually strongest when people are all heading to jobs in the same location. But in other ways, the relatively high concentration of residents and jobs throughout the region opens up opportunities for transit -- the demand for service is there.

Baby steps toward transit-oriented growth

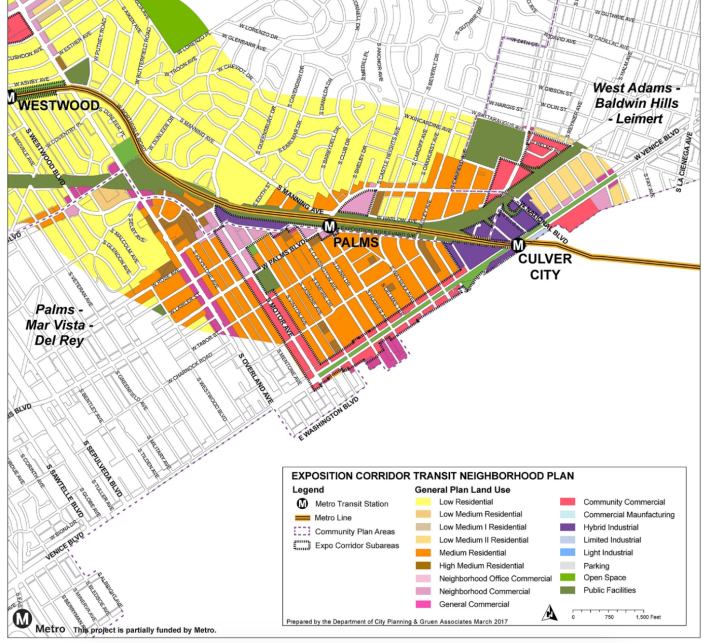

L.A. Metro and the Los Angeles city government are working to incentivize construction near transit stations. In 2012, with funding from Metro, the city launched its Transit Neighborhood Plans (TNPs), which aim to refine current zoning and street design around transit stops.

The city is concentrating on neighborhoods that will be served by transit lines currently under construction. "The ultimate goal is to foster transit ridership and to reduce greenhouse gases and improve air quality," said Patricia Diefenderfer, a city planner working on the TNPs. “We’re looking at how to create more capacity for housing and jobs. We’re trying to create environments that are more friendly for walking."

For the Expo Line, for instance, the draft plan calls for growth to be concentrated around transit stations, with a mix of uses and no minimum lot size requirement for housing. The plan also envisions making neighborhood streets safer and more comfortable to walk to transit.

Unfortunately, the TNPs generally don't touch areas zoned for single-family homes. That's a lot of land that won't be getting compact and walkable. In fact, along the Expo Line most of the areas close to most transit stations are zoned for single-family homes, shown in yellow below:

For Elkind, the TNPs are "real baby steps. They leave a lot of land open from rezoning, and that’s a real missed opportunity."

The broader obstacle to aligning land use with transit investments, beyond the hesitance of city agencies, is plain old local politics. "City Council members have a huge amount of control over their neighborhoods,” said Elkind. Some of those elected officials, he suggested, “may not care much about what’s happening in the denser parts of L.A.” and are happy to keep their districts car dependent.

These problems aren't limited to the city of L.A., which accounts for less than half the region's population. Reorienting land use and zoning around transit remains a challenge for each municipality in the region.

Kicking the parking habit

L.A. doesn't deserve its reputation as America’s most car-oriented city, but it sure commits a lot of land to moving and storing automobiles. The city alone has 18.6 million parking spaces. In the county, 140 square miles are used for roads and highways, and 200 square miles are devoted to parking -- put it all together and that’s significantly larger than all of New York City.

Current policies don't help matters much. Parking minimums compel new developments to include parking spaces, increasing costs for residents and creating inducements to drive.

To the city's credit, the Transit Neighborhood Plans have reduced parking requirements around the Regional Connector project downtown. Mixed-use buildings are allowed to "share" parking between their residential and commercial components, and developers of major projects have to "unbundle" parking from the price of rents, meaning people don't have to pay for parking spaces they don't use.

Overall, however, the TNPs don’t do enough to alter parking requirements.

Diefenderfer said that “reductions in parking can be very controversial,” especially on the west side of the city, like along the Expo Line. “We’re not being as aggressive as we might be” downtown, she suggested, because "in L.A., there’s a concern about increased density and impacts on traffic or neighborhood character.”

For its part, Metro has made an effort to cluster construction around its major stations through a joint development program that targets agency-owned property. So far, more than 2,000 units of housing -- a large share of which is subsidized -- and more than 1.5 million square feet of commercial space have been completed. Some of these projects, such as the Hollywood & Vine complex on top of a Red Line station, have added significant development within walking distance of stations.

Yet the agency's progress on this front has been slow compared to its construction of new transit lines. Despite opening more than 27 years ago, for instance, much of the Blue Line running south from downtown remains surrounded by parking lots -- some owned by the transit agency, like at Artesia.

Park-and-ride facilities still predominate around many stops, creating pedestrian-hostile environments. At North Hollywood (shown at the top of the post), where commuter parking was recently added, nothing besides a surface lot has been built in the 17 years since the subway stop on the Red Line opened. A major project is on the way, but the process shouldn't take decades. With L.A. Metro planning to open dozens of new stations soon, coordinating development with transit expansion should be a more urgent priority.

Grading land use in Los Angeles

L.A.'s development patterns have the makings of a transit-oriented region, with relatively high population densities. But city governments and Metro are not doing enough to prioritize the walking environment and shrink the footprint of cars and parking.

Strengths

- The neighborhoods around many L.A. transit stations already have relatively high population and employment densities, and the city is planning ways to increase growth in these areas.

- The city is working to change its zoning code to encourage walkable, mixed-use development around stations.

Weaknesses

- The zoning changes don't go far enough to reduce parking requirements and loosen single-family zoning restrictions.

- Plans for walkable development around transit stations take years to be implemented and don't address most of the city.

- Metro lets parking consume too much space around its stations.

Coming next

In the next Getting Transit Right post, I’ll delve into L.A.’s recent transit investments, including the Expo Line extension to Santa Monica and bus lanes on Wilshire Boulevard.