The vote to approve a transit funding ballot measure last November was a watershed moment for Indianapolis. After nearly a decade of intense advocacy, voters were finally given the opportunity to decide whether to pay for a vastly improved transit system. They jumped at the chance -- 59 percent agreed to tax themselves to increase bus service and build bus rapid transit lines. The City Council approved the tax earlier this year.

The 0.25 percent income tax will bring in roughly $54 million annually beginning this year. For a city where transit is so scarce, that's enough to implement some transformative changes.

Transit expansion in Indianapolis doesn't look very much like transit expansion in denser cities, where new rail lines are the big-ticket items. Nevertheless, what Indianapolis is doing deserves attention, especially from other spread-out American cities looking to spend their transit dollars as efficiently as possible.

The big change in Indianapolis is a complete reshaping of its bus system. The result, as I’ll describe in this installment of Getting Transit Right, will be like setting up a brand new transit network.

A grid of bus routes to change how people get around the city

Over the past few years, IndyGo (the city’s transit agency), the Indianapolis Metropolitan Planning Organization, and consultant Jarrett Walker and Associates have developed a plan for the city's new transit funding. The guiding principle is to transform a transit system that aims to cover a broad geographic area into one that's useful for a large number of people and trips.

Instead of operating a bus network that's perceived "as just a social service,” said IndyGo’s Brian Luellen, the system redesign aimed to ensure more people had access to better bus service at more times.

The hoped-for result, said Mark Fisher of the Indy Chamber, is that “you no longer have to plan your day around transit.”

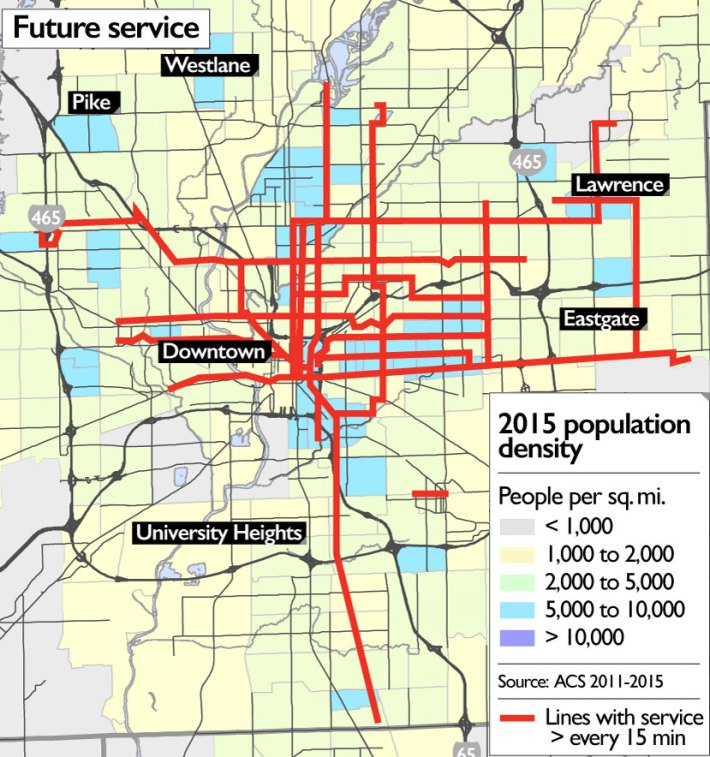

The new funding will pay to increase bus service by about 70 percent. The share of Indianapolis low-income households within a half-mile of a bus line that comes at least every 15 minutes will rise from 16 percent to 51 percent; the number of jobs near frequent transit routes will double; and all routes will operate seven days a week.

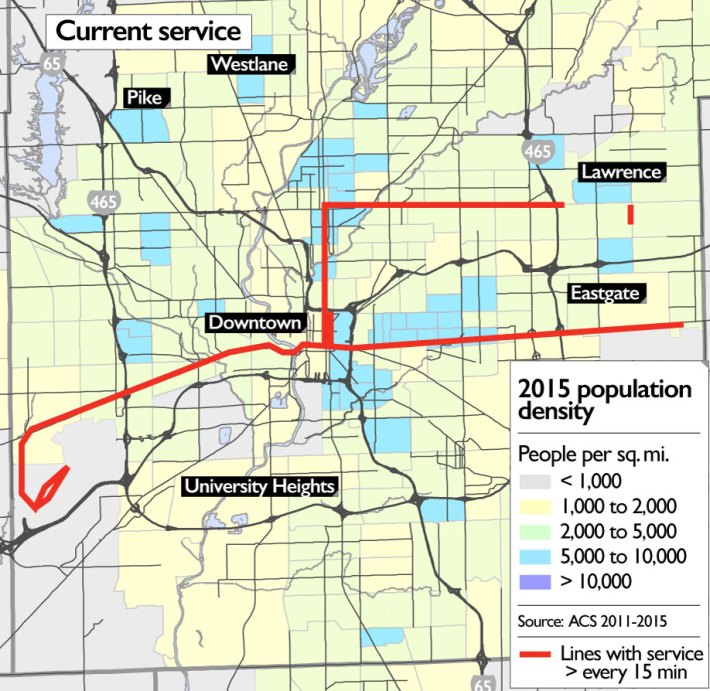

The most remarkable element of the plan, which is scheduled to be fully implemented by 2019, is the grid of frequent bus service in the city core. The current system relies on bus routes radiating from downtown that don't come very often, much like transit networks in many American cities that prioritize peak-hour service connecting outer neighborhoods to the jobs in a central business district.

This radial structure limits the kind of trips people can make using transit. If you want to get from one neighborhood to another, for instance, you have to wait for a bus that comes infrequently, go downtown, then wait to transfer to another infrequent bus.

In Indianapolis, this is a problem even within downtown, where destinations are far enough away from one another that people can't get where they're going without transferring. The new frequent bus grid will solve these problems in a few ways.

For one, buses will come much more often on several routes, so when people do have to make a connection, they won't have to wait long to catch the next bus. Currently, there are only three corridors where buses come at least every 15 minutes all day. The new bus grid will establish routes with at least 15-minute frequencies on a dozen corridors across the city, improving service to neighborhoods with higher population densities, particularly near downtown.

These network changes will also allow people to travel crosstown along several frequent east-west and north-south corridors. As such, riders will be able to get between neighborhoods much more easily -- they won't have to go out of their way and transfer downtown for those trips.

BRT as the spine of the system

Unlike most of the other cities investing in transit, Indianapolis is not proposing any new rail lines. While earlier plans had promoted rail lines crisscrossing downtown, the state legislature voted to prohibit anything other than bus service.

As a result, the transit plan focuses on high-quality, electric bus rapid transit. While the legislative restriction on rail is excessive, it's not harmful -- at least not yet -- because the city’s population and employment densities are too low to support rail. Spending on rail now would mean less money available for bus service that is well-suited for the city's current needs.

The proposed BRT network focuses first on the Red Line. The $98 million first phase of this route would run 13.5 miles north-south, connecting downtown with the Fountain Square and Broad Ripple commercial districts, a major medical center, the University of Indianapolis, and the state fairgrounds. The project is expected to begin construction this year and wrap up in 2019. It's projected to carry 11,000 daily passengers -- not bad for a city where total transit ridership currently numbers about 33,000 trips a day. It will be funded mostly by a federal Small Starts grant.

On the Red Line, passengers will pay fares before getting on the bus, speeding up boarding. Special vehicles with doors on both sides will enable stops at the curb or, on sections where buses run in center-aligned transit lanes, stations in the street. Service will be especially frequent.

About 60 percent of the corridor will be getting dedicated bus lanes, an essential element to bypass traffic congestion and ensure reliability. The bus lane design isn't ideal, however.

In some sections along College Avenue north of downtown, the project calls for one-lane, reversible busways. This is a risky compromise, intended to avoid alterations to street parking. It will require buses to wait at stations until the vehicles moving in the opposite direction have passed, which could detract from reliability. On other parts of the line, the bus lane will be shared with turning vehicles, a feature that may also reduce bus speeds.

On the south side of the Red Line, there won't be any dedicated lanes at all. IndyGo suggests that that’s because congestion isn’t a problem in those areas, but if that’s true, what harm is there in dedicating right of way to transit, particularly on the four-lane streets where the buses will run?

The second BRT corridor is the Purple Line, which will share some segments with the Red Line and serve the northeastern part of the city. It could be completed by 2020 if funding aligns as expected. Together, the two lines would be within reach of 90,000 residents and 150,000 jobs, a big portion of the region’s population.

Future efforts

Indianapolis has several other plans that are a bit further from realization. The Blue Line along Washington Street would serve one of the region’s most transit-dependent populations. Though the line would run on streets with five or more lanes in most places, it would have no dedicated bus lanes. That suggests the Blue Line won’t provide service up to the standards of the city's other proposed BRT routes.

Other projects will require support from suburban counties to move forward. IndyGo hopes to extend the Red Line north to Carmel and south to Greenwood, providing access to key suburban destinations. And it plans to invest in a Green Line BRT north from downtown to Fishers and Noblesville, home to significant job concentrations. But those services remain to be funded.

Grading transit expansion in Indianapolis

Indianapolis's transit plans offer big benefits at a low cost. With more bus service and a thoughtful redesign of the network, city residents will be able to take advantage of a much more reliable, frequent transit system. Ridership is certain to increase. While there are weaknesses in the design of new bus lanes, the city is setting a good precedent by dedicated street space to transit on the busiest routes, helping riders bypass car traffic and improving speed and reliability.

Strengths

- With relatively little additional money, Indianapolis will dramatically improve the frequency and reliability of its bus network.

- The city’s new bus network concentrates service in its most densely-populated neighborhoods, greatly increasing the number of people and jobs within reach of good transit service.

- The proliferation of frequent bus lines in a grid pattern will enable people to make trips by transit that were inconceivable with the old, infrequent hub-and-spoke system.

- A focus on BRT will provide appropriate service for a low-density city at a reasonable cost.

Weaknesses

- While the new BRT lines are a big improvement over existing service, dedicated bus lanes should be beefed up in many locations to ensure fast, reliable service.

- Because the counties outside Indianapolis have yet to raise new revenue, transit improvements that would reach major suburban job clusters are not yet funded.