Considering that it's America's 14th-largest city, Indianapolis has some surprises.

"We have horse farms in Marion County,” which shares the city's boundaries, noted Kim Irwin of the Indiana Citizens’ Alliance for Transit. A far higher share of households live in single-family homes -- 67 percent -- than in Midwest cities like Columbus (56 percent) or Milwaukee (46 percent). At the same time, Indianapolis has a dense downtown, featuring the Indiana statehouse and several major employers, where bus service could be much more useful if it were structured better.

As I noted in the previous Getting Transit Right post on Indianapolis, the city has a lot of catching up to do. Transit service is scarce and very few people use the existing system. A key reason for these lackluster outcomes is the city's sprawling pattern of development.

In this post, I’ll explore how the city’s built environment has shaped its ability to make transit work effectively. I’ll also investigate how the city plans to orchestrate new development around its planned transit investments.

One of America’s most sprawling regions

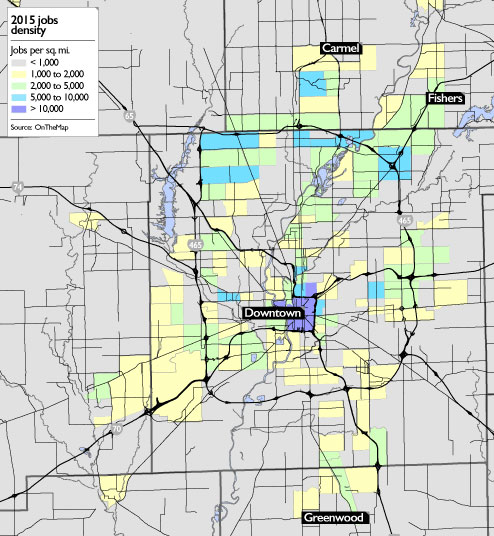

Indianapolis features a heavy concentration of jobs downtown largely within the backwards-C-shaped loop around the central area. The density of jobs works to Indianapolis's advantage, since small transit networks thrive most when service is concentrated on a central area. That’s particularly true because downtown is the place where the greatest number of residents can get to most easily, because of its geographic centrality.

Nevertheless, as the following map shows, the city also features significant job clusters far from downtown along the northern portion of the 465 loop highway. These jobs are harder to provide transit service to, since they’re in a car-dominated environment and far from downtown.

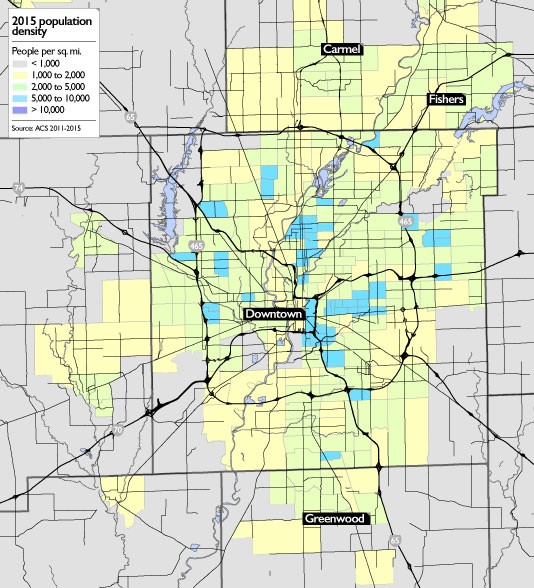

Meanwhile, the population of Indianapolis is very spread out, as the following map shows. Though there are pockets of moderately-dense neighborhoods, there are no neighborhoods with more than 10,000 people per square mile, which is the typical benchmark to support rail transit.

The population of Indianapolis’s built-up areas has actually steadily declined over time. Most neighborhoods near the center lost residents between 2000 and 2010. In the neighborhoods that were already built up in 1960, Indianapolis lost more than 200,000 people by 2014, according to my calculations. This was the second-largest percentage drop among the nation’s 20 largest cities.

At the far southwest and southeast edges of Indianapolis, some areas are literally rural. That makes extending service everywhere within the bounds of the city problematic.

A mismatch between the bus network and the shape of downtown

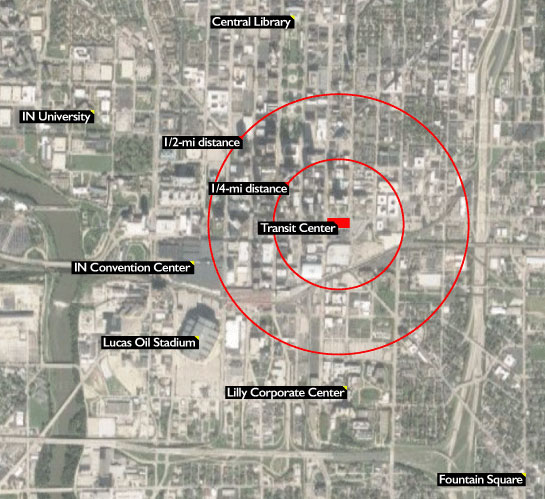

Indianapolis’s downtown extends out in a walkable grid from Monument Circle, around which stand the city’s tallest buildings and the Indiana State House. The city’s transit center, completed last year, is two blocks away.

Because of the city’s rather limited bus network, all IndyGo routes radiate from the transit center, meaning that people who want to get from the south side of the city to the north have to transfer. With service so limited, the wait to transfer between buses can be very long -- yet another disincentive to use the system.

But most transit trips are headed downtown, so theoretically people don’t have to transfer to get to their jobs, right?

It turns out that's not the case, because Indianapolis's downtown is too big for a service pattern where routes all terminate at the same point. Walking from the transit center to many major destinations is quite difficult. As shown on the following map, several major destinations, such as the central library, football stadium, and the headquarters of Eli Lilly, one of the city’s largest corporations, are more than half a mile from the transit center, essentially putting them outside of walking distance.

Someone taking a bus from the north side of town and attempting to get to the Lilly headquarters must either wait to transfer to another bus or go for hike. The same goes for trips in the opposite direction, like someone riding from the south to get to the central library.

No wonder, then, that downtown Indianapolis is so rife with parking. The Lilly headquarters and Lucas Oil Stadium, for example, are surrounded by vast acres of asphalt. The parking itself generates car trips, but the transit network also needs to be restructured to provide frequent, direct crosstown service. Better transit service patterns can support more walkable development, and vice versa.

Preparing for transit-oriented development

The city of Indianapolis has worked closely with the region’s metropolitan planning organization (MPO) on a strategic plan to encourage transit-oriented development. The document, released in 2015, forecasts 35,000 new units of housing in mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods in the region over the next few decades. If one person from each of those households commuted by transit each day, ridership would double.

A separate long-term plan from the city calls for more mixed-use development along frequent transit routes. According to Sean Northup, assistant director of the MPO, “the zoning downtown is all ready to go -- no parking requirements, no height limits.” In other words, the city is adjusting its regulations to support transit.

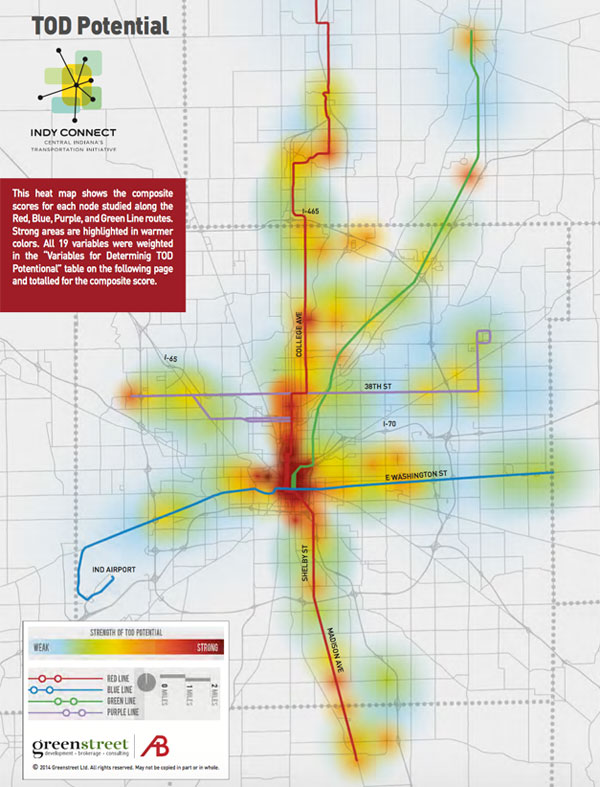

Both plans identify key areas along future rapid transit routes (which we’ll get to in a future post) where walkable, mixed-use development would be encouraged, mostly concentrated around downtown, as illustrated below:

Developers are buying into the idea that they should invest in housing that complements transit. Matt Impink of the Indy Chamber noted that “many partners are seeing where key opportunities are available to promote denser development along the line.” Milhaus Development, for one, has compact housing under construction along the north side of the city. And along East Washington Street, in a historically underinvested neighborhood, the community has laid the groundwork for future walkable development along a rapid bus route.

Grading Indianapolis land use

Indianapolis is one of the most sprawling regions in the country, and its low densities make effective transit difficult to provide. Looking ahead, there's cause for optimism, with the city and regional agencies developing plans to encourage transit-oriented development.

Threats

- Low residential and employment densities make providing effective transit service difficult.

- Many suburban job centers are auto-oriented and far from transit.

- Center-city destinations are not well-served by transit service radiating from a single hub.

- High levels of cheap or free parking downtown encourage car commuting.

Opportunities

- Indianapolis has been busy adapting its zoning code to encourage more mixed-use, low-parking development.

- Developers are responding with projects to meet a growing demand to live in walkable neighborhoods.

Coming next

In the next post in the Getting Transit Right series, we’ll explore recent changes in the Indianapolis transit system, with a specific focus on how the region has worked to connect suburban job centers to the bus network.