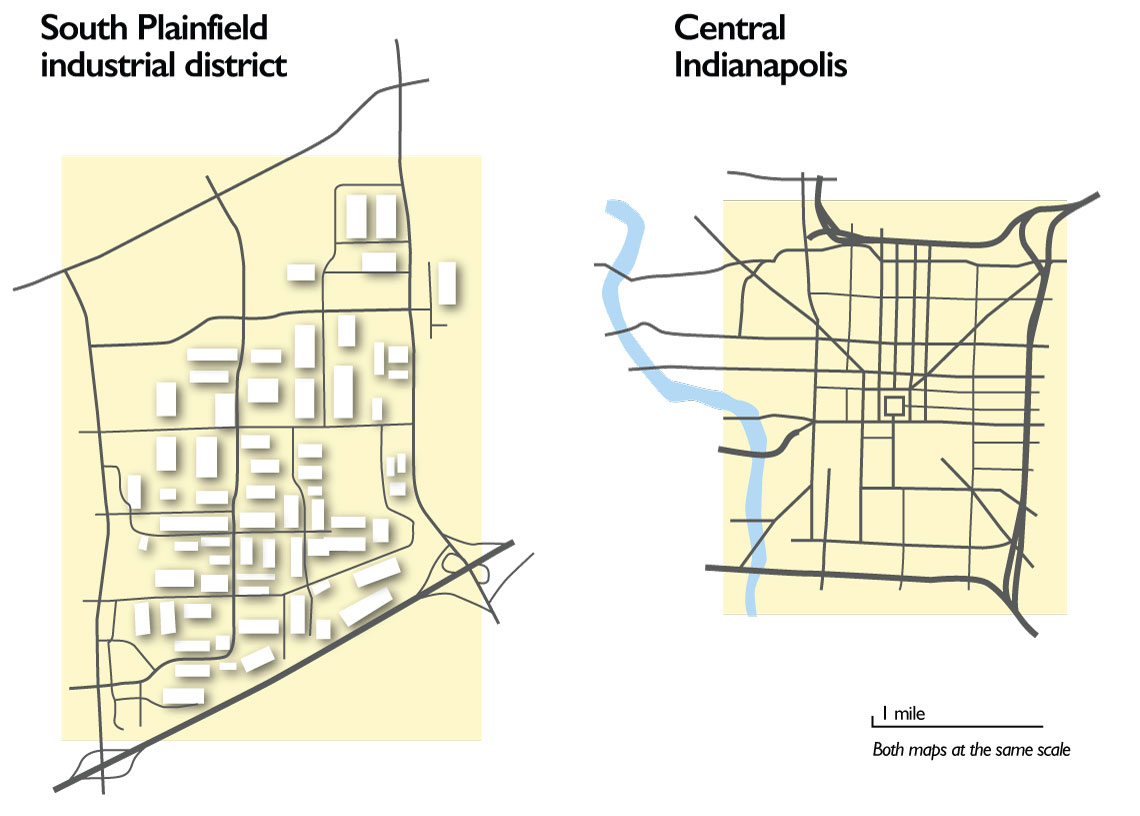

Like most places in America, the Indianapolis region is suburbanizing. That’s particularly true for jobs. Between 2002 and 2014, the number of jobs within the city's borders increased by 40,000 -- but that's far fewer than the 83,000 jobs added in the region's suburbs.

For industries like transportation and warehousing, in which employment increased by 30 percent, the trend meant more and more entry-level positions far from the urban transit network -- out of reach, in other words, for many people without advanced degrees who need those jobs.

It's hard for transit to serve job sprawl well, but to their credit, suburban employers and local governments have been working together to make the best of this situation. Other regions with big suburban job clusters can learn from what Indianapolis is doing to connect people to these hard-to-reach places via transit.

Connecting to suburban jobs

The suburban employment boom has been so inaccessible to Indianapolis residents -- especially people without ready access to a car -- that jobs have been going unfilled. “FedEx had 350 entry-level jobs, but they couldn’t get people to the job site,” said Mark Fisher, chief policy officer of the Indianapolis Chamber.

Transit in the suburbs is virtually nonexistent, so getting out of the central city by bus is a tricky proposition. CIRTA, the regional transit authority, has worked to fill this gap. It created a regional ride-sharing program and provided better information about how to connect between various services outside Indianapolis proper.

But those programs weren’t enough for many suburban areas. “We kept getting calls from people,” said CIRTA Executive Director Lori Kaplan. "They said, 'I have a job -- can you help me get there?'"

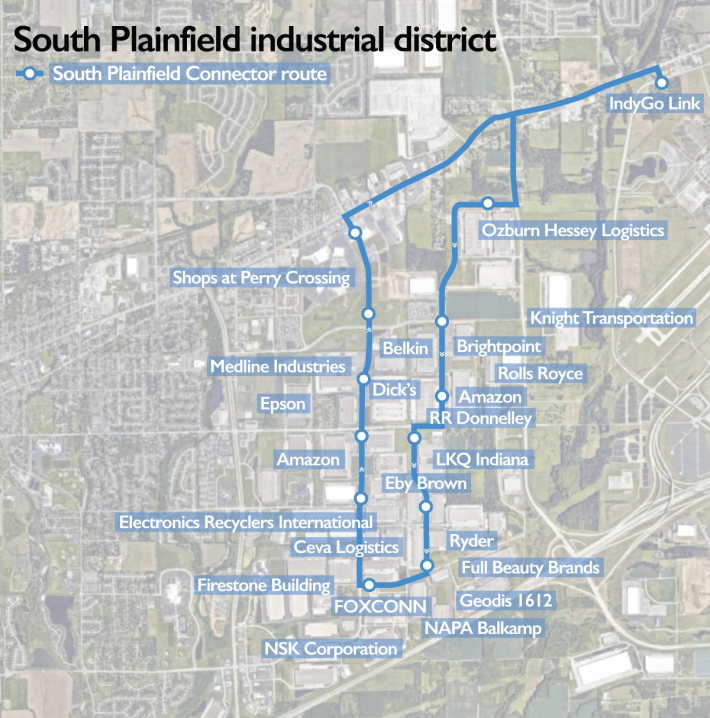

CIRTA applied for and received federal grants to fund new “workforce connector” shuttles designed specifically to link IndyGo’s bus network with large suburban employment campuses in Plainfield southwest of the city and Whitestown northwest of the city. In South Plainfield, the service connects to jobs at companies such as Amazon, Ryder, and Belkin, and runs every 20 to 30 minutes during rush hours. Those grants expire after three years, however, and CIRTA wanted a long-term solution.

The town of Plainfield agreed and supported CIRTA’s efforts to encourage businesses to pay for better suburban bus service. After receiving support from 70 percent of South Plainfield property owners, the town council enacted an Economic Improvement District that will charge property owners a small fee to support the connector service beginning this July. CIRTA is examining the possibility of extending this concept to other suburbs in the coming years.

Getting suburban employers to help pay for public transit is a laudable achievement, and it offers a clue about how other regions can provide bus service in otherwise transit-hostile areas. CIRTA’s service may be particularly relevant for the growing number of logistics parks, which have sprouted nationwide in areas isolated from residential neighborhoods, far from their potential workforce. It also suggests that companies even in heavily car-dependent places are aware of the need to improve transit for their employees and, in some cases, are willing to pay for it.

The creation of this revenue source required cooperation between CIRTA, businesses, and suburban governments -- . A special assessment district is only effective if it can take advantage of an economy of scale, charging a large number of property owners a relatively small amount for something they all share. As such, regions looking to emulate CIRTA’s successes may do best to identify districts with many employers, instead of trying to work with an individual company.

Investing in electrification

Indianapolis has also taken a major step forward from a technological perspective. Rather than continue to rely on diesel- or natural gas-powered buses, the city is pushing ahead on “converting our whole fleet to electric,” said IndyGo President and CEO Mike Terry.

IndyGo received a $10 million federal grant in 2013 for 21 electric buses to advance that ambition, and the city’s new Red Line bus rapid transit service -- which we'll cover in the next Getting Transit Right installment -- will be the nation’s first electric BRT line. The technological change aligns nicely with another local innovation, the BlueIndy electric car-share service, which has more than 100 stations throughout the city.

For Indianapolis residents, the move to electrification doesn't affect service, but it offers relief from pollution and street noise, making the city a better place to live.

Grading recent transit investments in Indianapolis

Despite very limited funding, the Indianapolis region has innovated by improving suburban bus access and putting electrified, zero-emissions vehicles into service. This suggests that transit officials are making a good effort to put their scarce funding to effective use, and it bodes well for the city’s future expansion plans.

What’s working

- Suburban municipalities, transit providers, and employers are teaming up on "workforce connectors" -- transit services linking more people to jobs.

- Electrification of transit vehicles is providing cleaner, quieter service.

What’s not working

- One suburban special assessment district does not equal a regional transit network. More transit integration across the region is needed.

Coming next

In the next post in the Getting Transit Right series, I’ll explore Indianapolis's plans for the future. It's an intriguing case study because Indianapolis is one of the few major American cities investing in better public transit without planning any rail lines.