Every year the federal government disperses a sliver of its transportation funds -- about $800 million, or less than 2 percent of the total -- to states expressly to support walking and biking. The states then distribute the funding to cities and towns to spend on specific projects and programs.

But there's a loophole, created at the insistence of congressional Republicans, that allows states to divert up to half the funding from this program, known as Transportation Alternatives, to car infrastructure. And a growing number of states are opting to take Transportation Alternatives money and spend it on roads, says Margo Pedroso of the Safe Routes to School National Partnership.

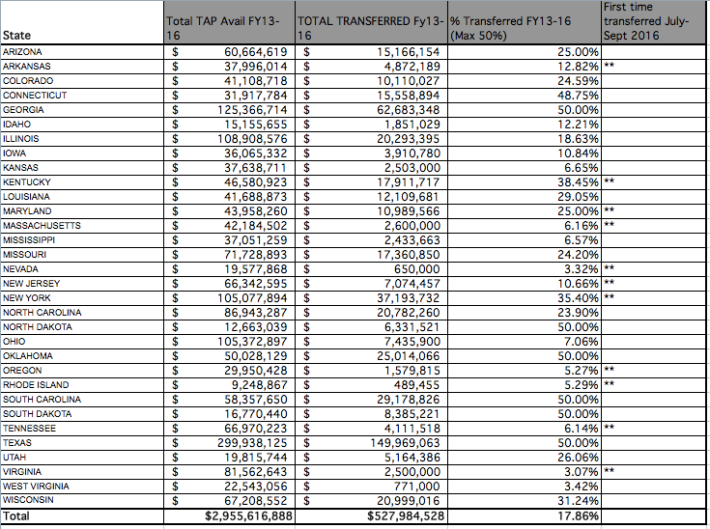

Some states -- including Texas, Oklahoma, and Georgia -- have always diverted the maximum. But the majority have recognized the value of walking and biking and used most or all of their Transportation Alternatives money for its intended purpose. Now that shows signs of changing.

In the third quarter of 2016, ten states diverted TA funds for the first time: New York, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee. New York has transferred $37 million out of the program; Maryland, $11 million; New Jersey, $7 million.

Even though Transportation Alternatives funding is small compared to the tens of billions of dollars in annual federal road funding, it can go a long way for cost-effective bike and pedestrian projects. In the last four years, Alabama has received $61 million for biking and walking projects thanks to the Transportation Alternatives program. "That’s a lot of money for Alabama for walking and biking," said Pedroso.

TA funding allowed the town of Prattville, Alabama, to build sidewalks around Prattville Elementary, a school in a low-income area, so children could safely walk to school. It also provided a grant to complete the Eastern Shore Trail in Baldwin County. Shifting this money around can doom or delay walking or biking infrastructure.

In some cases, there may be a reasonable explanation. Ohio, for example, transfers 10 percent of its funds every year to a separate program thats allow smaller metro regions to compete for the funding. Nevertheless, says Pedroso, the recent shift is alarming.

"I think it’s important for the people in the states being affected to contact the DOT and find out what’s going on," she said.

Advocates in some states have successfully fought attempts to loot TA funds. Pedroso says motivated New Jersey advocates were able to convince the state DOT to reverse its decision to divert money.

Below is a chart of all the states that have diverted TA money since the loophole took effect in 2013. If you want to get a clear picture of what your state is doing with these funds, you can email Pedroso at margo [at] saferoutespartnership [dot] org.