When he settled on Miami as his designated spot to escape Toronto winters, urbanist Richard Florida said he expected “all young people with a lot of gel in their hair.” What surprised him was finding a pocket of baby boomer urbanites from cities like Washington, DC, who came to Miami for its arts, diversity and walkability.

“Everyone said the same thing: We want a little bit of warmth, but we don’t want the warm, traditional Leisureville. We want an exciting community with arts and culture and mixing,” Florida said Thursday at the AARP-hosted “Conversation on Generations," with Atlantic editor Steve Clemons.

The wide-ranging chat between the Atlantic guys (Florida co-founded Atlantic Cities) explored the trends boomers could follow as they age -- and how governments should get ready.

Right now, “too many leaders are taking a ‘wait and see’ approach,” said AARP’s Nancy LeaMond, in her introduction. Half the country’s jurisdictions, she said, aren’t preparing for the so-called “silver tsunami” of aging boomers. And that can’t be very smart when over 10,000 Americans are turning 65 every day.

Florida’s take on his peers (born in 1957, he’s on the cusp of boomerhood) is that they don’t want to live in isolated homes or communities. On a fundamental level, that means seniors are choosing to live close to good airports, quality healthcare services, and, increasingly, the homes of their children and grandkids.

But there’s more to it than that. Florida and Clemons talked about an aspect of “cool" that hasn’t been traditionally associated with aging, with boomers in many ways replicating the trends of younger generations. Florida sees a craving “for a more experiential community … with coffee bars and restaurants and music clubs and street-level vibrancy,” and a diversity of ages. Losing steam is the notion that older adults only want to venture downtown for evenings at the opera.

Boomers also seem to get that walkability is key not only to creating this “interactive potential,” he said, but also to ensuring healthier lifestyles that promote longevity.

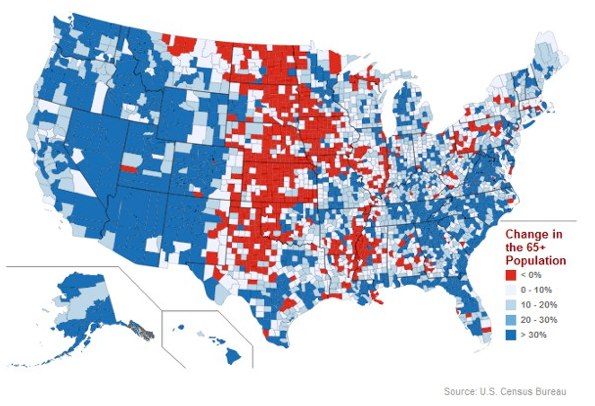

For these reasons and others, boomers are increasingly attracted to urban areas. A map in Florida’s article yesterday in Atlantic Cities charts evidence of this trend, with the center of the country (save for metro areas like Kansas City and Austin) losing the most seniors and the East and West coasts gaining.

Seniors are urbanizing for the same reason young people are, Florida writes: the “opportunity and the benefits that come along with density.”

In fact, boomers aren’t so distinct from the sector Florida defines as the “creative class” -- the knowledge workers, intellectuals and artists he believes are shaping the direction of cities and the economy at large. “The changes I associated with the creative class … I think they’re precipitated by the baby boom,” Florida said, crediting that generation with “lead[ing] the move back to cities.”

He recalled looking up to people a few years older than he who bucked “Leave it to Beaver” conventions and planted themselves in urban neighborhoods like the East Village or Dupont Circle -- at a time when, as Clemons put it, “cities [were] hellholes.”

Part of this movement, Florida said, might have come from boomers sensing in their own parents a lack of resonance with the suburban lifestyle. In his older relatives, Florida was struck by their sharp nostalgia for the pre-suburban lifestyles of 1940s and 50s Newark, New Jersey. “They pined for the sociability, the walkability … the Italian restaurants and pizzerias.”

Of course the “discomfort with suburbanization” Florida describes is not so across the board for boomers. He recounted a conversation with the influential urban theorist Jane Jacobs, who told him she admired the flower children for their anti-authoritarian “temper tantrums” of the 1960s -- but questioned why so many ended up going “right back to work the traditional way.”

It’s also notable that for a lot of boomers, the notion of “aging in place” is the ideal -- according to LeaMond, it’s what nine of 10 want to do. For many, that means sticking in their suburban homes. But even in denser urban environments, the concept poses challenges. “The key question,” she said, “is will their cities and their communities meet their needs as they age?”

Thursday’s conversation pointed to a number of focus areas for leaders and governments as they grapple to accommodate aging boomers. Among them:

City governments offer the most leverage for innovation. “If we’re going to put another three billion people in cities … and if we’re going to spend a couple trillion dollars in city building,” Florida said, the importance of local governments can’t be denied -- especially since, at the federal level, so many “are really clueless.”

City mayors, he said, “are the people who are closest to the ground, they’re the people who get it.” So what’s the answer? Elect good ones and encourage them to do more, he said.

Better training -- or really any training -- is needed. “For mayors and local development, there’s nothing,” Florida said. Clemons noted the upcoming CityLab conference, hosted by the Atlantic among others, as one attempt to address this deficiency. And Florida has called on Obama to create a "Department of Cities."

Many innovations can be achieved through dialing back the rigidity of antiquated zoning codes. There’s also a need for local leaders to shift focus from dramatic projects like convention centers and casinos toward elements “typically thought of as soft and frivolities” Florida said, like walkability, parks, and bike lanes.

Consider affordability. With many popular retirement cities becoming increasingly unaffordable, Florida and Clemons talked about the great potential of cheaper, smaller metro areas like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit. Such places already have the bones of great livable communities, Florida said, yet need a push to “make themselves more attractive and vibrant” for seniors.

In more established cities, Florida pointed to “the seeds of a generational conflict” in the wealth disparity between the older and younger residents moving in. As boomers bring their accumulated wealth to new environments, "we’re going to put a lot of pressure on urban housing markets," he said, making it "hard for 22- and 23-year-olds to compete."

Work on cross-generational solutions. “Mayors and economic leaders are obsessed with young people,” Florida said, while sheer numbers say "they should be obsessed with people my age."

But as LeaMond said, "this is not an old versus young issue." The services and amenities that benefit older residents -- like transportation, green spaces and healthcare -- also benefit the entire community. Said LeaMond: "A safe crosswalk for a senior is also a safe crosswalk for a mom and her kid."