This is the second installment in our three-part "Revolving Door" series about how cronyism in state DOTs leads to wasteful highway building. The first part profiled Ohio DOT chief Jerry Wray, who has switched back and forth between working directly for the asphalt industry and shoveling money to the asphalt industry as a public official.

Like Jerry Wray, Oklahoma DOT Director Gary Ridley has split his career between public office and lobbying on behalf of the asphalt industry. He started out in the mid-1960s, working as an equipment officer for the DOT. He climbed several rungs on the ladder and then left in 1997 to lead the Oklahoma Asphalt Paving Association, before returning to the department in 2001 as director of operations. In 2009, he was appointed to the top position in the agency.

The Oklahoma Asphalt Pavement Association made $3,000 in contributions to Governor Brad Henry's reelection campaign in 2006, three years before Ridley's appointment, and then donated $1,000 to the campaign of current Governor Mary Fallin in 2010. She had reappointed Ridley shortly after her confirmation.

Those are pretty small amounts in the world of political campaign money. But there are a lot of cozy ties between the road lobby and top politicians in Oklahoma, and Ridley is deeply embedded in the state's industry-friendly culture. One of Ridley's predecessors as ODOT director, Neal McCaleb, also worked as a lobbyist for the road industry, sandwiched between two terms as transportation secretary. McCaleb, reportedly a close political ally of Ridley, is now president of a road lobbying group called Transportation Revenues Used Strictly for Transportation. (TRUST -- get it?)

Upon Ridley's reappointment, McCaleb, acting as a representative of TRUST, called him the "best transportation director in the state's history." Republican Senator Jim Inhofe, one of the chief architects of the new transportation bill, MAP-21, went further, calling Ridley "the best secretary of transportation in the country." Inhofe, a well-known climate change denier, is a political darling of the oil and gas industry and fervent opponent of federal programs that support biking and walking.

Sure enough, Inhofe trotted Ridley out to testify before Congress on behalf of the more backwards proposals for the transportation bill last July. His testimony was a direct appeal to exempt states from requirements to invest in biking and walking:

This country’s CORE infrastructure is in a deplorable condition. Therefore, we support the ability for States to carefully scrutinize, prioritize and direct transportation funding that may be available for peripheral projects and programs.

Programs that mandate the commitment of dedicated transportation funding to recreational and fringe activities such as bicycle and pedestrian trails, complete streets, landscaping and historic preservation should be vigorously reviewed. If community livability projects and other similar programs are determined to be critically important to the viability and prosperity of the Nation, other funding mechanisms should be identified and the programs should be funded separately from core transportation infrastructure.

Tom Elmore, executive director of the Oklahoma City-based North American Transportation Institute, said it is an open secret that ODOT is focused as much, if not more, on serving the highway lobby as the people of the Sooner State. He calls Ridley "the P.E. with no degree," since Ridley does not have a college degree, but was awarded a certificate as a Professional Engineer because he passed a test. (The same test is no longer sufficient for the credential.)

"ODOT and the highway lobby are one and the same," Elmore said. "It’s very difficult to tell these days who is working for ODOT and who is working for the contractors because there is a such a revolving door."

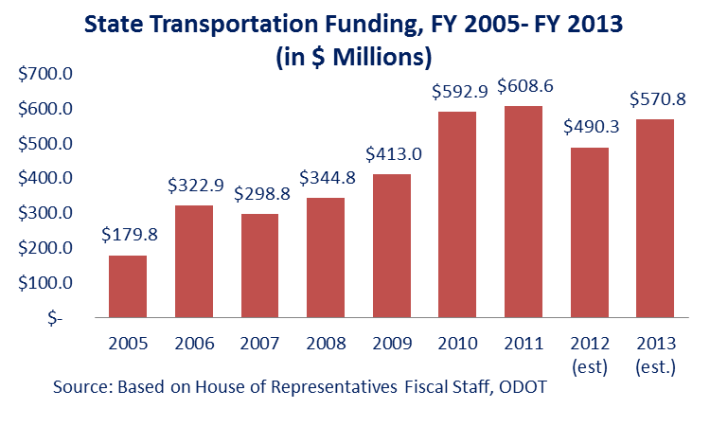

Recently, Oklahoma has opened up the spigot for road spending. In 2006, lobbying groups combined with friendly legislators to more than double the state's total spending on transportation, from $200 million to $470 million annually, which they proudly announced was achieved "without raising taxes." In other words, Oklahoma started dipping into its general fund. The Oklahoma Policy Institute noted that the state's transportation program was one of only two statewide agencies that hadn't seen cuts on the order of 20 percent following the recession.

OKPolicy said ODOT had made some laudable progress toward repairing road surfaces and deficient bridges, but that it was coming at the expense of other statewide priorities. The group implored state leaders to start thinking about an upper limit on spending, or having drivers directly cover more of the costs of the road system. Because while transportation spending has been skyrocketing, the percentage of that money that comes from drivers has been declining, since the state gas tax was never raised or indexed for inflation.

"It’s a very bad scene here," said Dr. Edwin Kessler, the vice chair of ethics group Common Cause Oklahoma and a board member at NATI. "The roads lobby is very powerful." And it doesn't want to see a transit or passenger rail revival, Kessler says.

"All one has to do is compare Oklahoma’s public transportation with some of the nearby cities such as Dallas, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Atlanta," he said. "All of these cities have good train service that helps the local economy."

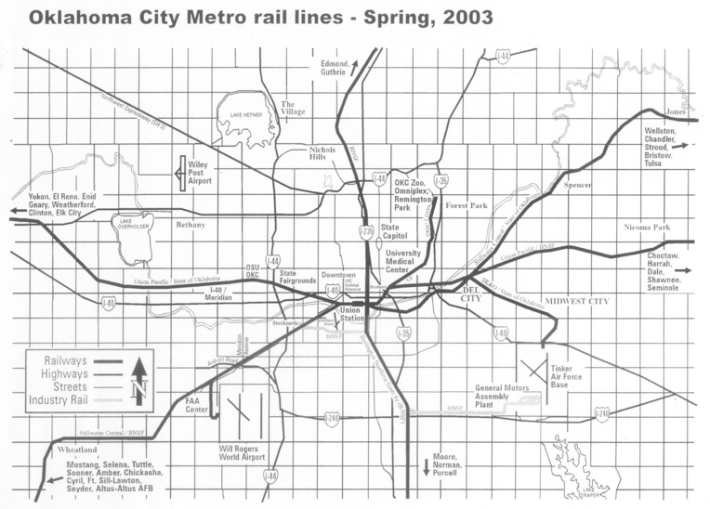

For years, NATI and Common Cause Oklahoma battled ODOT to preserve Oklahoma City's Union Station, a historic train station and rail yard. The 12-track rail station, near the heart of Oklahoma City, is grade-separated, with a beautiful, Mission-style building -- a "ready-made, urban passenger rail center," according to Elmore. The story of the station encapsulates how Oklahoma roadbuilders work the levers at their disposal at every level of government.

Union Station was abandoned in 1967, when passenger trains stopped serving Oklahoma City. But in the late 1980s, it looked like Oklahoma City was about to experience a rail renaissance. The city received $1.2 million from the Federal Transit Administration to restore the station as a multi-modal hub. Local governments contributed another half million dollars.

In 1996, shortly after McCaleb's second term as DOT director began, the state was researching new sites for Interstate 40, an elevated highway near downtown Oklahoma City. While the city had good reason to move the highway (Mayor Mick Cornett said getting the highway away from the riverfront helped "redefine downtown" in an interview with Streetsblog last week), the idea of relocating the highway to the abandoned rail center was seized upon by major contractors, engineering firms, and the state department of transportation, according to Elmore.

Seeking to preserve the site for passenger rail, NATI and Common Cause Oklahoma publicly opposed the proposal. But ODOT, they say, has been unwilling to engage with them, even to answer basic questions about revenue sources.

According to Elmore, Ridley is especially dismissive of these citizens' groups. "He said to me, 'Well, Tom, there was a time when we didn't even have to ask you what you thought,'" Elmore recalled. "Who's 'we'? He's talking about the highway lobby, the big bosses, the guys that really matter."

In 2007, the groups' challenge made it all the way to the federal Surface Transportation Board, which ruled that the railroad company BNSF made false or misleading statements in its application to abandon one of the rail lines needed for the I-40 plan. Without federal permissions to abandon the rail line, the project could not have moved forward. It was then that lobbyists began calling in favors from elected officials, Elmore said, prevailing on Jim Inhofe to pressure the STB into reversing their position and granting the state permission to abandon an important rail line.

Since his appointment in 2009, Ridley has been a major proponent of siting I-40 on the rail lines. While rail supporters were organizing to preserve the station, Ridley was threatening to cut highway funding to communities that went against the DOT on the issue, according to Elmore.

"He was the hand that carried it out," Elmore said.

Now, Oklahoma City's fate as a nearly passenger-rail-free city (it is still served by Amtrak) is pretty much sealed, Elmore says. The I-40 project is well underway, and over budget. Local critics joke that the project will give them "one highway for the price of three." Making matters worse is the fact that the state DOT has insisted on replacing the old highway segment near the riverfront with another grade-separated road, not an urban boulevard.

Short of spending hundreds of millions of dollars, Oklahoma residents no longer have a clear path to passenger rail, Elmore says, and the state's taxpayers have two asphalt industry representatives to thank.

"You just knocked out the state center for prospective rail passenger transportation, you wiped if off the map," he said."You could never replace the rail yard."