It's presidential election time in Ohio, and boy does Stanley Kurtz at the National Review have a scoop for the good, unsuspecting citizens of the Buckeye State. Northeast Ohio political leaders and President Obama are working on a sinister plot to redistribute wealth from suburbs and give it to cities!! (Socialism!)

Kurtz has found a bogeyman in the concept of "regionalism," which has for decades been promoted (and by that I mean talked about more than acted upon) by suburban and urban leaders alike in Northeast Ohio -- the most populous region in the state -- as a way to improve the region's economy by reducing government waste. Sounds pretty sinister, right? Well, Kurtz is sounding the alarm for Ohio suburbanites (coincidentally, the mightiest base of political power in the all-important swing state).

"The president and his fellow Democrats are coming for your tax money," writes Kurtz, a "fellow" with the Koch brothers-backed "think tank" the Ethics and Public Policy Center. "Redistribution is the goal, and suburban Ohio is target No. 1."

Before I explain how wrong and crazy that is, let's back up for a second. What is regionalism? Is regionalism socialism? Here is how the concept is generally understood in Northeast Ohio...

The problem, for Cleveland and its suburbs, is that there are 59 distinct municipal governments in Cuyahoga County alone. Each of these government entities manages a police department and a streets program, employs a council clerk, and so forth. That makes government service provision in Northeast Ohio relatively costly and duplicative. In other words, it makes taxes high. That is generally considered to be bad -- an obstacle to revitalizing the economy. And fixing the economy is priority number one in Northeast Ohio -- home to Cleveland, Youngstown, and other cities likely to appear on Forbes' annual Most Miserable Cities list.

"It's just laced with failed ideologies. It's fear mongering." -- William Currin, mayor of Hudson, Ohio

Okay, stay with me here. This fragmentation in government also encourages intercity competition for employers. This means that a lot of local governments spend substantial public resources luring businesses to hopscotch from city to city around the region, collecting tax breaks, without adding any jobs or true economic gain. Again, in Northeast Ohio, this is almost universally understood to be a bad thing. Out of 59 government entities, 49 have signed a voluntary "anti-poaching" agreement.

But to Kurtz, this kind of cooperation between suburbs and the central city is not common sense or good government -- it is self-evidently a diabolical plot.

Kurtz has a high-pitched, tone-deaf warning for Cleveland: Watch out, Obama is trying to make you like Portland, or -- gasp -- Minnesota. In Kurtz's writing, "Portland" and "Minnesota" are cautionary tales.

Kurtz uses Portland and Minneapolis as bogeymen not just because he holds their values in disdain. He is warning that policies they've adopted -- urban growth boundaries and tax-sharing agreements -- could follow from a few of Cleveland's rather toothless regional planning efforts.

But Kurtz isn't interested in discussing whether those tools might actually be beneficial to Ohio residents, whether they live in cities or suburbs. Nope. I mean, if you follow that line of inquiry you would have to arrive at the indisputable fact that both Minneapolis and Portland are far healthier places, economically, than Cleveland, whose absence of land use planning has helped make it an internationally renowned poster child for urban vacancy.

Kurtz doesn't go there. Just the suggestion that urban growth boundaries or tax-sharing could happen -- that is reason enough for suburbanites to hightail it from camp Obama, like, well, suburbanites from Cleveland. At least, that seems to be his suggestion.

It's true that voluntary tax-sharing agreements have been promoted by regional leaders in Northeast Ohio, most notably the Regional Prosperity Initiative, which -- radical left-wing organization that it is -- receives financial support from the regional chamber of commerce.

William Currin, the mayor of Cleveland exurb Hudson, is a leader of the Regional Prosperity Initiative steering committee, which helps promote tax-sharing agreements. He pointed out that these agreements are only undertaken voluntarily, and "everything they propose is of mutual benefit to the communities involved." Currin, who is a political independent, said he was disgusted by Kurtz's article.

"[Kurtz is] trying to politicize a nonpartisan issue: reducing the cost of government and protecting the sanctity of local government by collaborating with each other where we should collaborate," Currin said. "It's just laced with failed ideologies. It's fear mongering. They're trying to connect it to Obama. There is absolutely no connection at all. There is no grand conspiracy here under any circumstances."

Currin said his organization looks at examples like Louisville -- with its merged city-county government -- as a model as much as Minneapolis. He added that, as tax-sharing agreements have evolved in the Twin Cities, Minneapolis has become the biggest contributor.

If you actually examine the way money flows in Ohio, you might notice that suburbs and rural areas are often beneficiaries of "redistribution." Over the past few decades, for example, the state of Ohio and local governments have provided tax incentives for 14,500 jobs to move farther from the city of Cleveland.

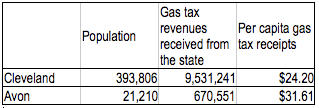

Ironically, Kurtz holds up poor victimized Avon, Ohio -- an affluent Cleveland exurb -- as an example. Leaders of Northeast Ohio's metropolitan planning agency, NOACA, forced Avon to agree to tax-sharing in exchange for a brand new interchange that was designed to spur private development, not solve any pressing transportation need. Numbers from the Ohio Department of Transportation, however, reveal Avon to be more a beneficiary of redistribution than a victim.

This chart shows shows per capita transportation spending in Avon (median household income $81,000) versus Cleveland (median household income $27,000) in 2009. It shows the direction that redistribution has long flowed in Northeast Ohio: out, out, out -- away from the central city.

According to a 2003 study by Brookings: "In Ohio, however, urban counties consistently took home a smaller share of state highway funds than suburban and rural counties relative to their amount of vehicle traffic (vehicle miles traveled), car ownership (vehicle registrations), and demand for driving (gasoline sales). On the flipside, rural counties received more dollars for each indicator of need than did urban or suburban counties."

What I want to know is, where were Kurtz and his friends at the National Review when that report was released? Did they decry "redistribution" from cities to rural areas? Of course not. The truth is, writers like Kurtz don't really have a problem with "redistribution" when it benefits their constituencies.

At its core, Kurtz's article isn't about policy. What he's is setting up is a discussion about identity -- suburban versus urban. And in many regions, including Cleveland, where the central city is 53 percent African American, Kurtz's ideas amount to a thinly veiled appeal to racial identity. You don't have to strain your ears too much to hear the sound he's making... it's a high-pitched whistle.