Nearly every time a new road is built, traffic volume increases beyond the predictions of the traffic studies. And nearly every time, transportation planners are surprised.

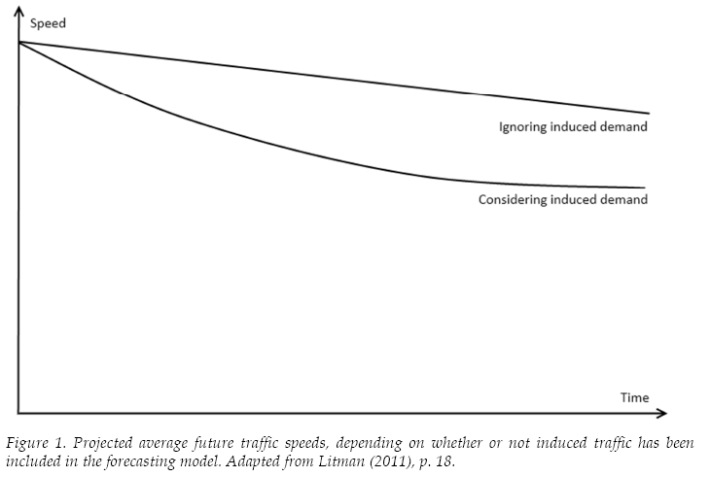

The explanation is a wonky little phenomenon called "induced demand." Essentially, if you widen roads to reduce congestion, people who were avoiding the road because of congestion will find it more convenient and take more trips, thus increasing traffic again.

So what do you have then? A big expensive project to eliminate traffic, and more traffic.

Induced demand has been widely studied; it was acknowledged by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials in 1957. Today it is widely accepted by transportation practitioners. The Clean Air Act even requires big cities to account for this effect in traffic modeling.

But many large metropolitan planning agencies refuse to comply, according to Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute [PDF], and smaller cities are under no obligation to do so. Futhermore, though they may account for certain types of induced demand -- extra trips -- they don't account for some of the long-term impacts of highway investments, namely sprawl.

That alone is enough to undercount the impact of induced demand. According to a 2005 study [PDF] set in California, "the net benefits of a suburban highway capacity expansion project declined by 50 percent if the project caused 60,000 residents (about 2 percent of the regional population) to move from urban to suburban locations, thereby increasing traffic congestion on that roadway link."

Failing to fully account for induced demand causes public entities to greatly overestimate the benefits of transportation projects and build more roads than is optimal from a financial and environmental perspective. And according to a new study out of Denmark, that's exactly what's happening.

According to the study, completed by researchers at the Institute of Transport Economics and a Danish university, this leads to skewed cost-benefit analyses that call for new highways and road widenings of dubious benefit to the public.

Researchers reported that perceived time savings make up the largest portion -- sometimes 85 percent -- of the economic benefits assigned to prospective highway projects. But an unanticipated boost in traffic volume can turn many projects that would theoretically pass analytical muster into economic losers. Unless transportation agencies are carefully accounting for these effects, however, many of these projects get built anyway.

The Danish study focused on Scandanavian countries, but its authors said the results should be applicable internationally, wherever transportation agencies are not fully accounting for induced demand.