We see it over and over again in our cities. Migration out of central cities hollows out neighborhoods and leaves the people who remain struggling with the consequences of disinvestment. But when development returns to urban areas, the arrival of new residents can impose burdens on people who never left. Often, as amenities come into an area and crime goes down, property values rise and poorer residents can no longer afford to live there.

Even when the new development is built around transit, which can lower transportation costs for low-income residents, unintended consequences can ensue.

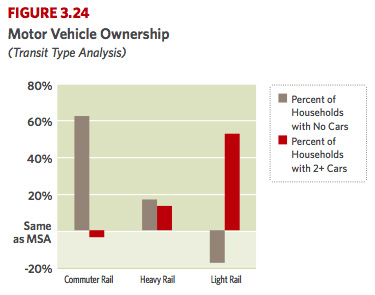

Researchers with the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy have recently reached some provocative conclusions from their study of gentrification and transit-oriented development. Without proper planning, they found, new development near transit can lead to stratified neighborhoods and higher rates of car ownership.

They also offered some solutions to ensure that transit-oriented development achieves its intended goals. The solutions include preserving affordable housing and restricting parking in new developments.

Historically, the authors note, transit-rich neighborhoods tend to be diverse. The low-income people and people of color who live there often don’t have cars and they depend on public transportation. They also usually rent their homes -- and since rental housing turns over faster than owner-occupied homes, this speeds along the process of gentrification when new transit options come to a neighborhood.

Rents go up as transit arrives (often along with new shops and restaurants) and more affluent people move in. And guess what? Those wealthier people tend to have more cars. That’s the fundamental paradox: the people who are attracted to transit-rich neighborhoods – and have the money to pay more to live there – don’t use transit as much as less affluent people who can get priced out.

The authors stop short of calling this pattern “displacement” – they point to “normal processes of housing turnover and succession.” But what’s clear is that the people moving in are from a different income demographic than those moving out (though the researchers say the racial makeup tends to stay the same).

Income-based housing stratification and more cars are not the outcomes planners want from transit or transit-oriented development. The challenge is to keep development around transit from becoming too exclusive and too car-oriented. How can communities do this?

The report comes with an entire policy toolkit for communities planning new transit (especially light rail, which, according to the research, brings about even more profound change than other forms of transportation.)

In San Leandro, California, they’ve implemented a comprehensive strategy to preserve existing affordable housing and add more. In Minneapolis, the Longfellow neighborhood negotiated benefits that the city then incorporated into the development approvals -- making the deal binding. In all cases, ensuring broad public participation in the process was essential.

But having your say is one thing. Actually being able to afford your own home next year and the year after -- that’s what counts. In Denver, Charlotte, and the Bay Area, communities used transit-oriented development acquisition funds to buy or preserve affordable housing before transit projects came in and drove up land prices and property values.

Some other tools in the equitable TOD toolbox:

- Housing trust funds, which are dedicated sources of public funding for affordable housing

- Low-income tax credits, allocated by state housing agencies to developers to provide money for affordable housing

- Tax increment financing districts, which use the revenue from the higher property taxes in the surrounding area to help finance the building and preservation of affordable housing

- Inclusionary zoning ordinances requiring some proportion of new units to be affordable (usually 10-25 percent, but sometimes more)

- Housing incentive programs that fund transportation-related livability infrastructure in affordable housing projects, which reward local communities for the creation of affordable housing near transit

These are ways to maintain affordability and to keep the existing residents from having to leave. But you also have to incentivize transit use among the new residents, who have the means to drive a lot if they choose. Stephanie Pollack, the lead study author, says it’s just as important to have “transit-oriented neighbors” as to have “transit-oriented development.” One of the most important levers, it turns out, is parking policy.

Here's what she told an audience at Rail~volution about one transportation package she negotiated in Boston.

This is what the package looked like: it was designed to get at the issue of creating transit-oriented neighbors who would use the transit. One parking space per unit, priced separately from the condo… shared parking spaces in the same garage so people would make their second car a shared car; and a free annual transit pass for your first year after purchase, provided by the developer, who by the way will spend way more on a second sub-surface parking spot for each unit than that annual transit pass will cost them.

You have to think about the market housing in transit-oriented neighborhoods. We’re so focused on ‘we need affordable housing’ – because we do – but we still want the people living in the non-affordable housing to be good transit neighbors.

“Unbundling” parking from the price of the unit is key. People don’t notice the cost of car ownership when it’s folded into the cost of their housing, and car-free residents effectively end up sharing the cost of providing parking for car owners -- they don't get the full financial pay-off of eschewing a car. But when faced with the prospect of paying $100 a month for parking in your own building, the benefits of going car-free – especially in a neighborhood newly equipped with good public transportation – suddenly sound like a good deal compared to the costs of owning a car.