This week on the Talking Headways podcast, Chris and Melissa Bruntlett discuss their newest book Women Changing Cities: Global Stories of Urban Transformation.

We discuss the mobility of care work and the unpaid labor that undergirds the economy and the women getting elected to get things done.

Scroll past the audio player below for a partial edited transcript of the episode — or click here for a full, AI-generated (and typo-ridden) readout.

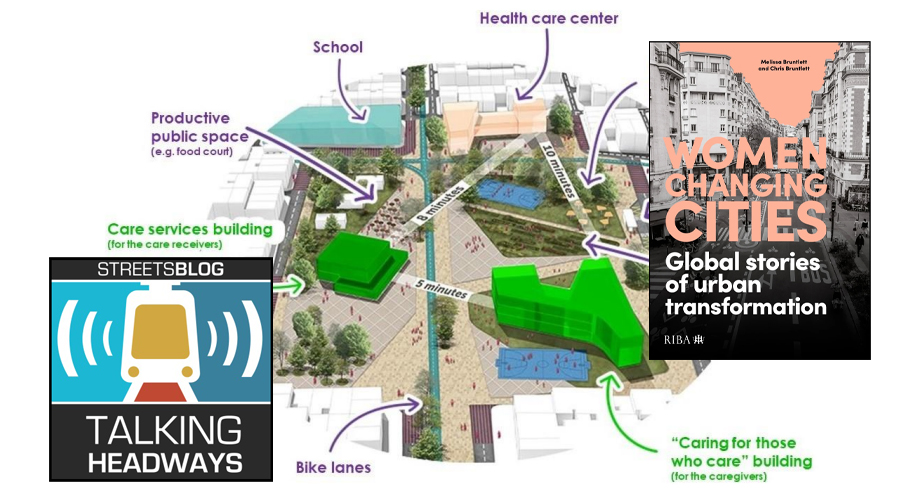

Jeff Wood: There’s a number of themes in this book. The first one that stuck out to me is the idea of the infrastructural care. "Care blocks" in Bogota, the idea of time poverty, life stage benefits of the superblocks in Barcelona, getting more women on bikes in different cities around the world.

We started, at least in the U.S. during the last administration, we started having more discussions about getting this idea of care infrastructure into legislation and things like that, but it seemed to fizzle out a bit, even though the problems still linger. I'm wondering why this specific topic is so important to you all and why it showed up so much in the book.

Melissa Bruntlett: Yeah, I mean I think it's put quite eloquently by Kalpana Viswanath in the chapter about Safety Pin from Delhi, that, you know, care work, which is all of the things that somebody does in our lives that is unpaid, but is, like, the function of daily life — is the foundation of everything. Like we, we do not leave the house, we don't get up in the morning and have breakfast and, you know, have a shower and leave for work without somebody performing some active care for us.

And the same goes in terms of how people move through our cities. And I think that the reason that it's coming out more is, you know, as we slowly shift towards this idea that not all transport is about economic gain, it's not about going to work and coming home again, we start to understand that those trips are not the same. It's about going and dropping kids off at school or doing groceries or, you know, running errands for your household or even for yourself, and they're shorter. They're usually, you know, under, well one-to-five kilometers or whatever that is in miles.

Jeff Wood: It's about three miles.

Melissa Bruntlett: Three miles, thank you. But, yeah, these trips are so better facilitated by walking and cycling or good public transportation networks.

That's why we started to see that shift. And maybe we didn't understand that it was related to care work at the beginning, but you know, as that starts to become more of the conversation, you're realizing, oh, these are the trips that have to happen, and how are we already not making that easier? Not just for women, but for everybody. And I think that's why we saw it. We're seeing it increase. And I'm hoping even though, you know, in the US, you're experiencing a bit of a pause, let's say, it'll come back,

Chris Bruntlett: We dipped our toe into this topic with the "feminist city" chapter of our last book Curbing Traffic, and tried to put our finger on what we had been writing about for many years, and by delving into this topic, the mobility of care.

I think we had this a-ha moment as advocates that departments of transport and cities are so hyper-focused on the single purpose of the long-distance commute from the house to the office — it's at the expense of all of those other myriad journeys that we take in a day that are maybe non-economic and that are related to care. Only something like 16 percent of trips are work-related trips. So we ignore that at our peril, really. And they are, as Melissa said, often made by some combination of walking, cycling and public transport. We don't measure them, we don't design for them. And it's often those people, those trips, are made silently suffering while we’re widening motorways and throwing infinite resources at making traffic jams a little bit more efficient.

That's only gonna get you so far. We're gonna eventually run out of money and space, and at some point we have to pivot and say, "Okay, what are the other journeys that are happening in our city and how can we support them? And what are the lived experiences outside of our own?"

And that was the common thread, as you say, in a lot of the cities that we spoke to and the perspectives that the women leaders brought — was they had a very personal experience with being responsible for the care in their household. And so they brought that perspective and they prioritized that in their decision making. And that's how you get things like school streets and superblocks and good cycling infrastructure that connects to your public transport system. That only happens when you prioritize care in your neighborhood and in your community. So we're hoping to shine a light on that particular topic and give other people a similar a-ha moment.

Jeff Wood: I mean, the totals and the idea that there's, like, and I know that there's a lot of folks who wanna put a monetary value on it, but the amount of unpaid labor that is happening at all times is astonishing. You know, it undergirds the whole economy, even though people don't wanna acknowledge it.

And so those numbers are so huge. It's very, uh, amazing that we haven't actually pulled that to the surface.

Chris Bruntlett: Yeah, in the Bogota chapter, you know, they try to put numbers on it and, I don't remember them off the top of my head, but as you say — it's a huge number.

Jeff Wood: I remember a trillion or something in there. It was a huge number.

Chris Bruntlett: That's why they're creating infrastructure like the care blocks to try to support that, knowing that women are still disproportionately burdened by this unpaid care work by on average by two to three hours a day.

And if we can reduce that deficit and give them support through childcare, through laundry services, through myriad other support systems, then we can level the playing field, figuratively speaking, and give them more opportunities because this is part of the structural and cultural reason why women aren't succeeding and being lifted up to levels of decision making and leadership and why we have that gender gap that's so prominent in our structures of government and other means of employment.