E-bike safety advocates like myself have long warned about “bikelash”: the predictable backlash that occurs when policymakers misdiagnose the e-moto problem as an e-bike problem. The recently enacted — and extraordinarily restrictive — New Jersey law is a textbook example of bikelash unleashed. It is also a case study in legislative malpractice.

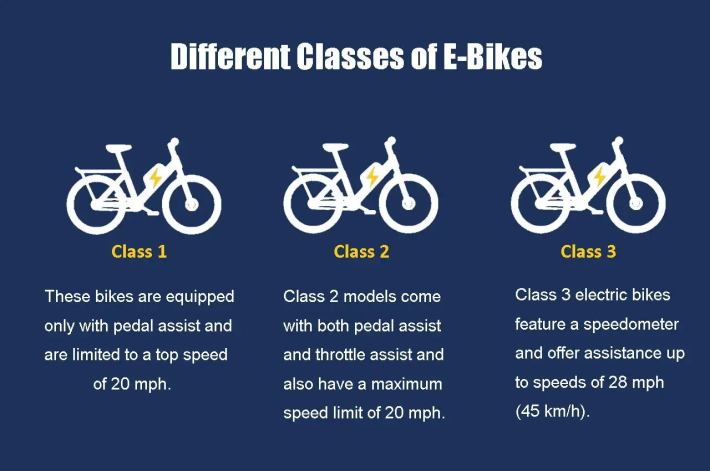

The law was reportedly triggered by the tragic death of a 13-year-old riding what was described as an “e-bike” in a collision with a truck in Scotch Plains, New Jersey. In response, the New Jersey Legislature sprang into action — discarding the widely adopted three-class e-bike framework used by most states and replacing it with one of the most restrictive regimes in the country.

Under the hastily enacted law, New Jersey now effectively treats all e-bikes as motorcycles. It imposes a minimum riding age of 15 and requires licensing and registration. If actually enforced, the law will inevitably discourage lawful e-bike use, push riders back into cars, and increase congestion, pollution, and — perversely — traffic fatalities.

Before other states rush to follow New Jersey down this path, it is worth recalling a basic principle from medicine: "diagnose before prescribing." Shouldn’t legislators first determine what vehicles are actually involved in serious crashes before wielding a legislative sledgehammer?

Here is what the New Jersey Legislature would have discovered had it done even minimal investigative work.

The crash that started this mess

Through a public-records request to the Scotch Plains Police Department, I obtained a photograph of the vehicle involved in the fatal crash.

It was not an e-bike.

Multiple AI tools narrowed the vehicle to a small set of possibilities, with the Ebox V2 emerging as the leading candidate. I contacted the manufacturer directly, and the company confirmed in writing that the vehicle was indeed an Ebox V2.

According to the manufacturer’s own specifications, the Ebox V2 is a 2-kilowatt electric motocross bike capable of speeds of at least 32 mph — before any unlocking or modification. That is more than twice the motor power allowed for throttle e-bikes and far above legal e-bike speed limits.

In short, it is not an e-bike. It is what we — and bike industry group PeopleForBikes, which has spearheaded the adoption of the three-class system — call an e-moto. It is not street-legal in New Jersey or in most states.

This distinction matters.

Most states already have ample laws on the books that, if enforced, would remove illegal e-motos from public streets and school campuses. Enforcing those existing laws should be the first priority. Doing so would be the most meaningful tribute to the 13-year-old who lost his life riding an illegal e-moto — not mislabeling the problem and punishing lawful e-bike users instead.

Legal malpractice

Of course, e-bike laws should not be immune from scrutiny.

As the New Jersey episode illustrates, manufacturers and retailers who market electric motorcycles as “e-bikes” are killing the golden goose. In counts I have conducted at more than two dozen schools in the San Francisco Bay Area, the vast majority of throttle-equipped devices cross the legal line from e-bike to e-moto — findings echoed in a recent Mineta Transportation Institute study commissioned by the California Legislature and reported in the New York Times Magazine.

Law enforcement officers across the country report difficulty distinguishing lawful e-bikes from illegal e-motos. (No, simply bolting pedals onto an electric motorcycle does not magically convert it into an e-bike.) To facilitate enforcement, a serious, fact-based discussion about treating throttle-only devices as motorcycles may well be warranted. That is a conversation worth having.

What New Jersey has done, however, goes far beyond that. Its law sweeps in pedal-assist e-bikes, eliminates the three-class framework altogether, and imposes motorcycle-style restrictions across the board — all based on a fundamentally flawed diagnosis.

If a doctor treated every patient with chest pain by amputating a limb, we would call it medical malpractice. When legislators do the policy equivalent, it deserves the same label.

Let’s hope New Jersey reconsiders its approach — and that other states resist the temptation to commit the same kind of legislative malpractice.