More than one-third of Americans can't legally or physically drive, belong to households that can't afford a car, or otherwise can't rely on a personal vehicle to meet their daily travel needs, a new report finds — and that means millions of people are being left behind due to car-centric policies.

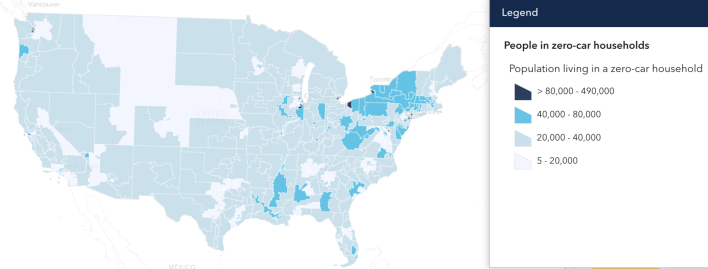

In what may be the first detailed analysis to systematically count the number of people who aren't served by autocentric development in the United States, analysts at the Natural Resources Defense Council found that roughly 16 million U.S. residents belong to households that have no access to personal vehicles at all — a number that represents one in twenty people.

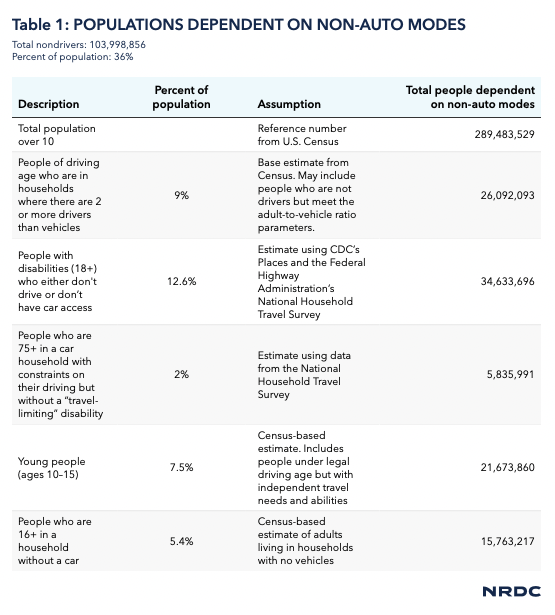

That astonishing number, though, is just the tip of the iceberg. The researchers estimate that nearly 104 million U.S. residents can't reliably use a personal automobile to get around, including many people with disabilities and people living in poverty — as well as tweens, younger teens, and many elders who should be capable of navigating their cities independently, but can't always safely or legally get behind the wheel.

Altogether, that represents a staggering 36 percent of the U.S. population; only 25 percent of total transportation infrastructure spending, meanwhile, flows towards transit, biking, and walking.

Worse, because the federal government doesn't bother to count non-drivers — and state and local governments generally don't either — multimodal advocates are often told that everyone drives in their community, so there's little point in supporting those that don't.

"We often hear advocates asking how many people don't drive in their jurisdictions when trying to engage with their policymakers," said Ali Lehman, the NRDC's mobility choices research associate and the co-author of the study. "Personally, I think this is a big opportunity to correct [the myth] that people who don't drive are [living] some sort of fringe lifestyle — that not having access to a car is something that only hippies do, or people who are obsessed with biking. Because as the report details, there's a lot of nuance [here.]"

For Lehman, those nuances paint a sobering portrait of just how misaligned America's transportation policies are with the realities of how people actually move through their communities.

During her analysis, Lehman found that a shocking 34.6 million U.S. adults — or about 12.6 percent of the entire U.S. population — either have disabilities that physically prevent them from driving, like vision impairments or neurological disorders like dementia, or belong to a household that doesn't have a car for some other reason, like not being able to afford one.

Of the one in four Americans who self-identify as having a disability, 24.9 percent of adults under 65 live in poverty; retrofitting a van to be wheelchair accessible and operable with hand controls, meanwhile, can cost more than $30,000, while other types of vehicle modifications may cost even more.

"[A lot of times], people will push for car infrastructure [by saying] that cars are necessary for people with disabilities," Lehman adds. "And that is probably true for a lot of people — but there are also a lot of people who can't drive because of their disabilities."

Another 5.8 million Americans — or fully 2 percent of the population — identified as seniors over 75 without disabilities, who say they can still drive sometimes, but might, for instance, struggle to see after dark. That leaves countless seniors essentially housebound at night unless they can catch a ride with someone else, or have the good fortune to live in a neighborhood that makes other modes convenient.

And then there are the kids, whose mobility needs are rarely discussed by transportation officials who assume that all caregivers can double as private chauffeurs. The researchers found that 21.6 million U.S. residents, or 7.5 percent of the population, fall into the age range of 10 to 15, when they're too young to legally drive in most states but theoretically old enough to walk or bike to school and other destinations alone — or they would be, if their communities were safer.

Even adding up all those people, though, is still likely an undercount of the "non-driver movement", to quote a term coined by disability activist and Week Without Driving co-founder Anna Zivarts. (In her own back-of-the-envelope calculation, Zivarts estimated that 30 percent of Americans couldn't drive, but acknowledged that this number probably didn't paint a full picture.)

For instance, the NRDC researchers weren't able to include people who have lost their licenses due to criminal convictions, or who couldn't get one in the first place because of their immigration status. People who are temporarily disabled because of things like injury, illness, or medical treatments that make driving unsafe also aren't included, even if those temporary disabilities last for years.

None of that, by the way, counts the people who don't drive by choice, even if they technically have a car in the garage that they reported to the National Household Travel Survey, from which the researchers pulled much of their data. And if all those non-drivers are invisible to researchers on the hunt for non-drivers, that means they're even more invisible to policymakers and transportation officials, who are shaping our transportation decisions around the belief that virtually all of their constituents have easy access to a car.

"The assumption that everyone drives [underlies] how our system has been built out," said Samantha Henningson, NRDC's senior transportation advocate at the co-author of the report. "I think that's just a cultural norm — and also, a norm of how our transportation dollars get spent."

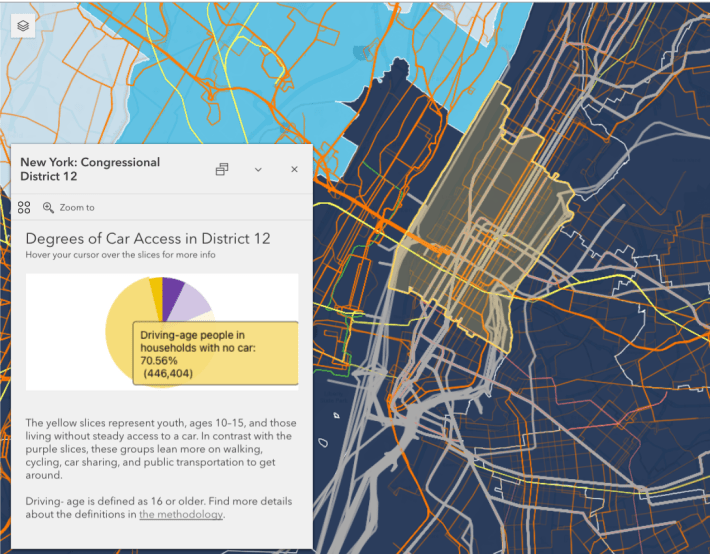

Of course, both Henningson and Lehman stress that being car-free isn't always a burden. In their dashboard, overlaid transit maps reveal that many non-driving hotspots like Manhattan (above) are rich in other mobility options that can make life without a car safer, healthier, more affordable and more connected than life with one.

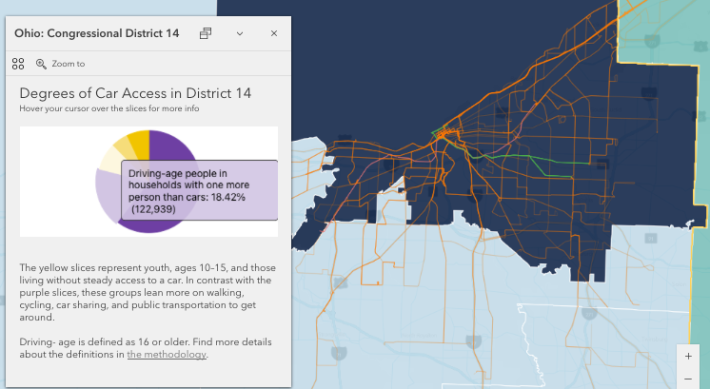

But both researchers caution against assuming that all communities with high concentrations of non-drivers are rich in transit options.

For instance, roughly 40 percent of residents of Ohio's 14th district — which contains the city of Cleveland — live in a household with fewer cars than people, ranking them among the districts where residents are least likely to have personal vehicles in the U.S. Only 10.5 percent of residents of Cleveland proper ride the city's transit network, which runs infrequently relative to many larger cities, and whose routes thin out significantly outside of the downtown core.

Of course, the researchers weren't able to determine why, exactly, cities like Cleveland have so many non-drivers — and they acknowledge that sometimes the answer isn't simple. One person who forgoes car ownership might have a disability and ethical objections to contributing to climate change every time they fill up a gas tank; another might want to buy a convertible the minute they can afford one because they're a car enthusiast, even if there's a great bus line running right outside their door.

Regardless of why Americans are non-drivers, though, Henningson says policymakers need to acknowledge that non-drivers still exist in massive numbers, despite a century of building a transportation system that pushes hundreds of millions of people towards car ownership — and they always will, if for no other reason than because cities cannot geometrically accommodate every single adult and child driving (or being driven in) a personal automobile.

And as Congress gears up to pass the next federal transportation package in 2026, they must take action to give non-drivers more and better mobility options — and not to be surprised how quickly their ranks grow when they do.

"Transportation has been politicized in a way now that it hasn't been previously," she adds. "With the surface transportation reauthorization upcoming, we need to give policymakers tools look at these groups who are overlooked in planning decisions."