Editor's note: this article originally appeared on IIHS insight and is republished with permission.

What do you consider the right speed for traffic on a neighborhood street? Your answer may depend on whether it’s in your neighborhood or someone else’s. Is this just one of many roads you take on your drive to work? Or is this where your kids play and your neighbors walk their dogs?

The question of the right speed is one of perspective. For decades, lawmakers and traffic engineers primarily saw things from the point of view of drivers. But that is changing. Increasingly, states and communities are considering the needs of nonmotorists — and are slowing vehicles down.

When I first started out in transportation engineering, the field was centered around vehicles; the goal was to make traffic move smoothly and minimize delays. The safety and comfort of pedestrians, bicyclists and other nonmotorists wasn’t a priority.

This lack of attention to pedestrian safety over the years has likely contributed to the high rate of pedestrian deaths in the U.S. today. Pedestrian fatalities make up nearly a fifth of all road deaths and have increased 78 percent since reaching their low point in 2009.

Fortunately, our field has begun to wake up to the need to protect pedestrians and other vulnerable road users. Transportation agencies are turning to new strategies — including lowering speed limits.

Changing the default

On most residential streets in the U.S., the default speed limit — the one established by state law that applies when no speed limit signs are posted — is 25 or 30 mph. Similar default speed limits apply to roads in urban or densely populated areas. These speed limits influence travel speeds, but they don’t necessarily bring them down to levels that low; many people routinely drive 5 to 10 mph above the posted limit.

Small changes in vehicle speeds lead to dramatic changes in the chance that a pedestrian can survive a crash, my IIHS colleagues recently found. At an impact speed of 20 mph, there’s an 18 percent risk that a struck pedestrian will be severely injured. At 30 mph, that risk increases to 50 percent. At 40 mph, it rises to 81 percent. Clearly, lower speeds are essential if we want to make our neighborhoods and cities safer.

A growing number of cities are reaching that conclusion and lowering their default limits or assigning lower limits to more streets. In 2016, the default speed limit in Seattle was changed from 25 to 20 mph on nonarterial streets (typically residential streets) and from 30 to 25 mph on arterial streets. In 2017, the speed limit on Boston streets was reduced from 30 to 25 mph in places without a posted speed limit sign. Portland, Oregon, lowered the speed limit on most residential streets to 20 mph in 2018 and has continued to reduce speed limits on higher-speed roads. This year, Albany, New York, reduced the speed limit to 25 mph on city streets.

My colleagues and I have studied the effects of lowering speed limits in urban areas: After the changes, the percentage of drivers traveling at dangerous speeds declined in Boston, and crashes on arterial streets were less likely to cause severe injuries in Seattle. So why aren’t more communities doing it?

For one thing, local governments don’t always have the authority to make these changes — at least not without jumping through some hoops. State laws often require local communities to perform engineering studies to justify a lower speed limit. These studies typically examine traffic volumes, crash history, road design and current travel speeds. They’re expensive, and they can take a long time.

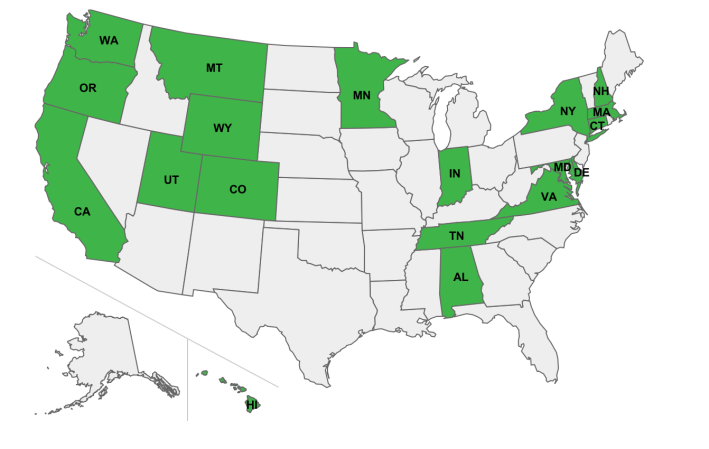

Since 2013, 19 states have changed their laws to give local governments more flexibility and authority to lower speed limits within their jurisdictions. In some cases, this means waiving the requirement for an engineering study or for state approval of specific changes.

One such measure is Sammy’s Law, a 2024 New York law named after Sammy Cohen Eckstein, a 12-year-old killed by a speeding driver in Brooklyn. It grants New York City the authority to set speed limits as low as 10 mph on some streets, even though the state-mandated default for the city is 25 mph.

If laws in more states were amended to make it easier for jurisdictions to change local speed limits, we could see lower speed limits in more communities. But that’s not the only obstacle.

86ing the 85th

The practice of setting speed limits around the 85th percentile speed — the speed that 85 percent of drivers are traveling at or below in free-flowing conditions — can be another hurdle for local communities seeking to lower speed limits.

This method, which in effect lets drivers make the rules, does not account for the vulnerability of road users outside of vehicles. In addition, a speed limit set this way is a moving target: After a speed limit is raised to meet the current 85th percentile speed, a new, higher 85th percentile speed usually emerges.

State and local agencies have started to establish alternative speed-limit-setting methods in residential and densely populated areas that allow engineers and planners to prioritize the safety of all road users.

The most recent edition of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which governs all road markings, speed limits, stop signs and traffic signals across the U.S., places less emphasis on the 85th percentile speed in setting speed limits and requires consideration of road contexts such as land use, nonvehicle road users, and crash history. It explicitly discourages using the 85th percentile speed method to set speed limits in urban and suburban contexts.

Guidance from the National Association of City Transportation Officials calls for setting safer speed limits in cities by focusing on context-appropriate speeds. For example, it recommends a 25 mph speed limit on major roads and 20 mph on minor roads within city limits.

In states where localities don’t have explicit authority to lower speed limits, there are usually still some options. If the process for conducting engineering studies is not formally established in state law or standard practice, local jurisdictions can request permission to use a locally defined process that is different from the 85th percentile speed method. If states require setting speed limits based on the 85th percentile speed, local jurisdictions can sometimes request an exemption by citing robust crash and injury data. In almost all states, local jurisdictions have the authority to create slower zones around schools.

Our 30x30 vision

Recently, IIHS-HLDI launched a new vision called 30x30, which targets a 30 percent reduction in fatalities by 2030. Achieving this goal will require actions that can take effect immediately. Lowering speed limit is one of them. Once approved, it is quick: all that needs to be done is to change the signs.

That said, reducing speed limits is just one of the tools in the speed management toolbox, and it’s not always the right one for a given situation. Other ways to effectively reduce speeds include engineering changes such as speed bumps and lane narrowing, speed feedback signs, and better enforcement through speed safety cameras — though the latter often faces the same hurdle of state authorization before localities can act. Even when speed limits are lowered, jurisdictions should consider adding some of these other measures to enhance the speed reduction effects and achieve long-term, sustainable results.

In city halls, state legislatures and transportation departments around the country, a shift away from a vehicle-centric mindset has begun. The sooner we can get decision makers everywhere to adopt this new perspective, the safer all of us will be.