Every year on Oct. 31, I post up on the front porch of my 19th-century duplex and hand out candy to hundreds of trick-or-treaters.

My neighborhood is a mixed-income former streetcar suburb a 15-minute bike ride from St. Louis's Gateway Arch, so it's a natural Halloween hotspot, blending dense blocks of multi-families (read: maximal candy volume) with stately Victorians on postage-stamp lots (read: full-size Snickers). For one magical day every year, I get to watch my street transform into the realm of tiny pedestrians, who come from all over town to show off their costumes and take part in the adorable Gateway City tradition of telling a spooky joke in exchange for a treat. (Yes, there are a lot of variations on "What does a witch eat at the beach?")

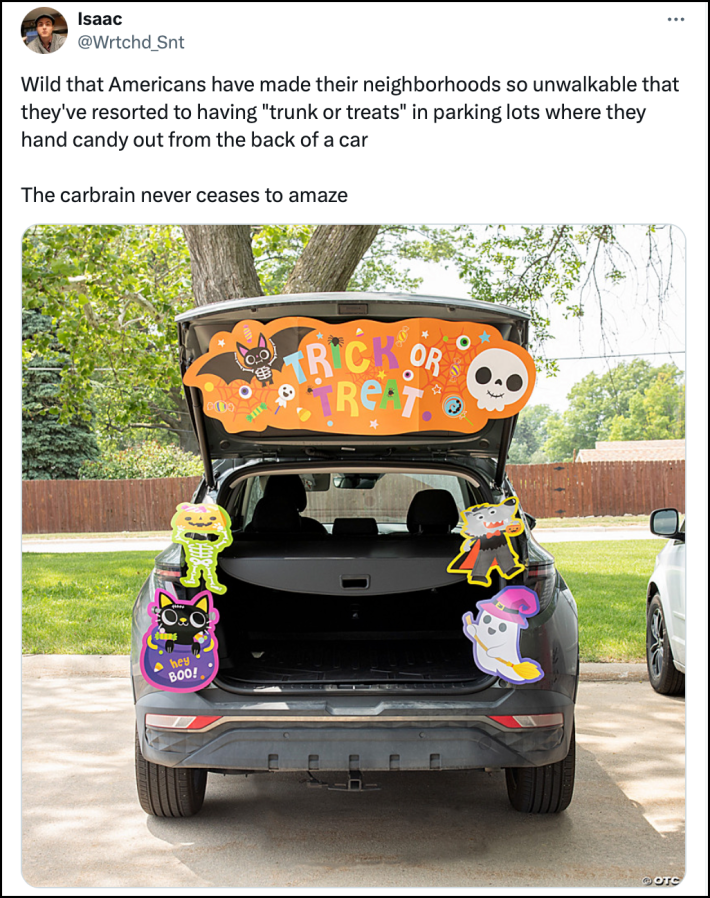

Of course, there's a reason why my walkable street is overrun by little ghouls and goblins from all over the city: because truly Trick-or-Treater-friendly neighborhoods like mine are, increasingly, a dying breed. And during the course of that die-off, we've introduced what many sustainable transportation advocates treat as a monstrosity, even if I don't quite agree with them: the Trunk-or-Treat event.

Dating back at least to the late 1980s, Trunk-or-Treat has become a mainstay of countless, American childhoods, as well as something of an extreme sport for competitive parents hellbent on having the most Halloween-tastic Hyundai around.

For many urbanists, though, the idea of celebrating a major holiday in a parking lot is a particularly painful symptom of the disease of mass automobility, which has demolished walkable neighborhoods like mine with the cruel efficiency of a villain in a slasher movie — only to replace them with sidewalk-free suburbs full of large-lot McMansions with abysmal candy-to-kid ratios.

To be sure, we should be terrified of the impacts of mass car dependence — and not just in sprawling exurbs during spooky season. Even the denizens of America's densest neighborhoods live in constant fear of traffic violence, which is the second-leading cause of death for kids under 19, behind only gun violence; for kids under 12, cars are still the leading killer.

On All Hallow's Eve, meanwhile, pedestrians under 18 have historically been three to ten times more likely to be killed by a driver than on any other day of the year. And that's not just because of the sheer ubiquity of little walkers on Oct. 31; impaired and distracted driving both spike on my favorite holiday, and many communities don't take steps to protect the children that flood their trick-or-treating routes after dark, like closing them to car traffic and giving lanes back to families on foot.

Building our places around cars — and driving more dangerously on the roads that run through them — has also created legions of neighbors who rarely see each other except from behind their respective windshields. That's helped shred the civic trust that makes caregivers comfortable accepting a homemade bat-shaped cookie from the family down the block, or makes homeowners comfortable answering the door to a teen in a party store Ghostface mask.

It's no wonder so many Americans cram their crossovers together in the parking lot behind the church every Halloween; the rest of the world is just too scary.

To say that the Trunk-or-Treat phenomenon is only an echo of those very real problems with our built environment, though, is missing a crucial nuance in the conversation about how to make America less car dependent — one that, in my opinion, poses a real risk the entire movement.

Let's just be real for a second: a lot of people love Trunk-or-Treat, and not just because car dependency has made the back-end of a Buick more inviting than the average American neighborhood. Walking a few blocks with a screaming toddler in a Bluey costume can be a nightmare, even in a New Urbanist paradise where houses are built close together.

That can be doubly true for kids or caregivers with certain mobility-limiting disabilities, or those who, because of food allergies or social anxiety, just feel safer getting their sweets from a few pre-vetted, familiar neighbors — even if those neighbors are operating out of the back of their SUVs.

The movement to end car dependency, ultimately, is not the movement to end cars, or any of the deeply ingrained car-centered community rituals that come with them. It's about giving people options about how they move through and relate to their cities — so everyone can choose to trick-or-treat in their neighborhood one night, and trunk-or-treat with their school community the next.

Done right, I'd even argue that Trunk-or-Treat can actually show what's possible for our cities when we don't build them around cars — by putting kids in a place where none of those cars are moving, and each vehicle is transformed into something infinitely more delightful.

Again, let's be real here: the "trunk" part of "Trunk-or-Treat" is kind of incidental. Spend two minutes on any Mommy- or Daddy-blog devoted to the holiday, and you'll find thousands of cars so thoroughly disguised as fortune teller booths and game show sets and elaborate homages to Jurassic Park that you might not even be able to spot a vehicle underneath.

For many families, the pick-up or SUV is little more than a convenient way to transport their community theater-style Titanic set from which they'll dole out candy — and when the kids arrive, they see a village of whimsical mini-wonderlands, and aisles full of wide-open asphalt where they can walk without fear.

Trunk-or-Treat isn't often talked about in the same breath as other creative placemaking endeavors like National Park(ing) Day, in which Americans repurpose a space traditionally reserved for private automobile storage and give back to people and highlight the potential of car-light spaces. But maybe it should be.

And maybe we could even talk about extending that ethos outside of the car and the parking lot, as advocates in San Francisco recently did when they set up a park-or-treating event along a road they're soon hoping to close to vehicle traffic.

At the end of the day, the movement to end car dependency won't be won by hectoring suburban and rural families for enjoying a Halloween event that happens to involve a bunch of cars in a parking lot. It will be won with smart policy that makes walking to a neighbor's door on October 31st a no-brainer for most of us, because the street is safe from violent drivers, the houses are built close by, and the neighbor is someone we regularly see and trust while we ride our bikes or wait for the local bus.

And I'd argue that we'd probably be more successful at winning those policy changes if we embraced the fact that Trunk-or-Treat will likely always be a part of American life — just like tail-gating at football games, and pick-up truck floats at the Labor Day parade, and all the other ways that automobiles have become deeply woven into our culture. Because at the end of the day, ending car dependency isn't about prying away anyone's long-held traditions, or even prying away anyone's individual car: it's about giving people more freedom to make a wider range of choices.

And if the throngs of kids that come to my neighborhood every Halloween are any indication, families will always choose trick-or-treating in safe, walkable neighborhoods. We just have to build more of them.