Not so fast.

An emerging technology that would enable vehicles to communicate wirelessly with each other to prevent deadly crashes is one step closer to moving ahead — but advocates are sounding the alarm that tech is no substitute for simply redesigning roads for safety.

Last week, U.S. Department of Transportation officials, safety activists, and private sector auto technology representatives unveiled a plan to speed up the installation of "vehicle-to-everything" technology in cars and highway infrastructure across the country. The Biden administration has high hopes for the so-called V2X to reduce fatalities, which have been on the rise over the past decade.

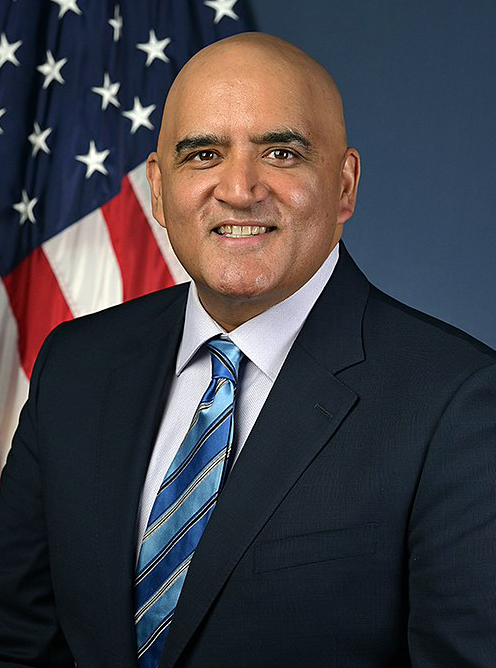

“The DOT exists for two reasons: to save lives and make people’s lives better,” Federal Highway Administrator Shailen Bhatt said at a press conference in Washington. “I am unaware of a more significant technology we can use other than V2X to save lives and make people’s lives better.”

But some transportation advocates warned that governments should simply focus their efforts on old-fashioned, low-tech solutions like redesigning roads, boosting transit, encouraging active transportation and reducing America’s dependence on cars to prevent the 42,000 traffic deaths that occur each year.

“While any technology improvement designed to help keep pedestrians safe can be a good thing, it ignores the primary culprit of the problem: the design of our streets leads to deadly interactions between cars and pedestrians,” said Eric Cova of Transportation for America. “Just as much energy, if not more, needs to be put toward design changes that make streets safer for folks outside of cars.”

The technology isn’t exactly new. A V2X-enabled vehicle sends out a burst of radio signals with information about the car’s size, speed, and direction to other vehicles in a roadway and issues their driver a warning if they are at risk of getting into a collision. The signals can also be sent without a direct line of sight at a better range than sensors that currently exist in vehicles.

But the sensors can have difficulties identifying people in poor weather conditions, and some tech leaders are concerned about data sharing and tracking, and the obvious vulnerabilities to hacking by nefarious actors.

How did we get here?

V2X has been discussed since the Obama administration proposed requiring it in all new cars and light trucks, but the Trump administration nixed the plan in 2017. President Biden revived it in a national roadway safety strategy and a draft of a V2X deployment plan in October 2023. And the bipartisan infrastructure plan also included $60 million in grants for using V2X in a handful of states including Texas, Arizona, and Utah.

V2X is currently operating in a handful of states. Denver uses V2X to help its buses and snow plows have signal priority, and one historic building in the city’s downtown added V2X software to an electric vehicle charging station. Utah is adding sensors to all of its highways.

Government officials and tech leaders don’t just want to put V2X in cars and charging stations. They envision wireless sensors on bicycles and buses, swaths of interstate highways, intersections in urban areas, and even on pedestrians' smartphones. Someday, V2X systems may even be able to seize control of an autonomous vehicle and prevent it from veering off the road, although that aspect is still being developed.

“That’s the future we’re looking toward where all the users of the system could broadcast it,” Bhatt said. “Rather than relying on drivers, who have shown themselves to be distracted or drugged, we're going to rely on the technology to broadcast the presence of the vulnerable users. It’s not just on drivers who are being distracted in the environment.”

But not everyone will have V2X — or want to have it — on them every time they go outside. And some advocates argue that the development of a new technology does not absolve transportation leaders from ensuring that public roads are safe for all users in the first place.

“This sounds like another American way to avoid the basics like reducing car access to urban centers, traffic calming and building more transit,” said Jon Orcutt, the director of advocacy at Bike New York, and a former city transportation official. (A U.S. DOT official said the agency continues to call for roadways designed to encourage safe travel behavior.)

The next step will be getting the Federal Communications Commission to approve the final technical rules on V2X. Department of Transportation officials expect the FCC to release them in the coming weeks.

Bhatt said the delays are ultimately worth waiting for as long as the technology saves lives in the field.

“Nothing in this world worth doing is easy. We come to do hard things and these are things we should fight for,” he said. “It is hard to push for things that are going to save lives because people don’t know that you're going to save their lives.”