A new bill could restore a key legal principle that gives regulators more power to protect the public — including protecting pedestrians and cyclists from automakers that would put cars on the road that are more likely to kill people outside them.

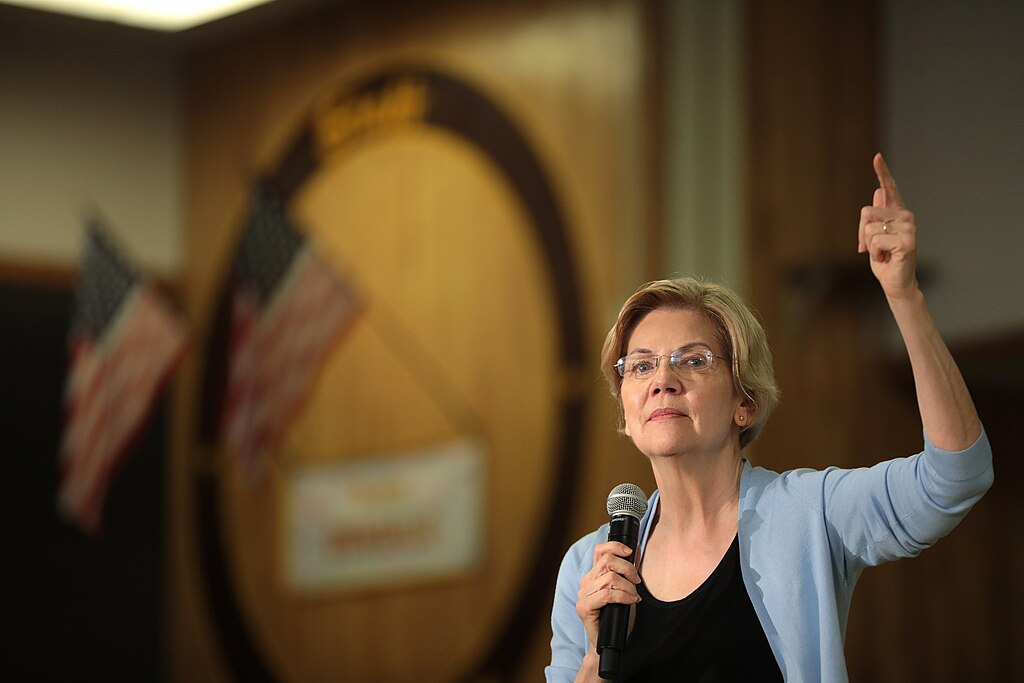

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) recently introduced the Stop Corporate Capture Act, which would both codify the famous “Chevron Deference” — which gives regulators, rather than the courts, the final say when a regulation is unclear — and erect new regulatory bulwarks against influence from lobbyists.

That includes not just creating a 120-day time limit for the White House to review new regulations, but authorizing federal agencies to reinstate rules that Congress rescinded, as well as reforming the cost-benefit analysis process that precedes new rules, so things like child safety and preventing discrimination are valued more highly.

“The Stop Corporate Capture Act is a comprehensive blueprint for modernizing, improving, and strengthening the regulatory system to better protect the public,” Rachel Weintraub, executive director of the Coalition for Sensible Safeguards, said in a release. “The bill would enhance our government’s ability to deliver results for workers, consumers, public health, and our environment. And it would level the playing field so that ordinary people – not just big corporations – can weigh in on potential rules that affect them.”

So what is Chevron, and what does it have to do with curbing traffic violence?

Before the Supreme Court ruled against the Chevron doctrine, whenever a regulatory statute was deemed ambiguous in court, the federal agency responsible for that statute could count on its interpretation trumping that of the court, as long as it was reasonable and in the public interest.

The court’s 6-3 decision to strike Chevron down, though, defaults all manner of regulations to judicial review going forward — rather than to agency experts.

Because Chevron has been the law of the land for so long, though, the legal code is chock full of intentionally vague statutes, which lawmakers wrote under the assumption that regulators would eventually fill in the gaps in their legislation — especially when it comes to laws about vehicle regulations, at topic about which few Congresspeople are experts. That intentional ambiguity often gets compounded even more by the inherent bipartisan give-and-take needed to get legislation across the finish line in a deeply-divided political climate.

"Our concern, of course, is that if there is ambiguous language in any congressional directives, agencies will be reticent to meet or exceed [those directives]," explained Cathy Chase, president of the nonprofit Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, in recent interview with Streetsblog.

"For example, the automatic emergency breaking rule that was just issued exceeded the congressional directive by including pedestrian detection. So will there be a chilling effect moving forward on the agency taking action such as that? [Will] the agency always ... go to the least common denominator?"

Without Chevron, Chase fears that most of the auto safety and emissions regulations delivered by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law are now up for challenges in court. This includes the automatic emergency braking rule, a potential requirement for impaired driving prevention technology on new cars, and updated federal auto consumer safety ratings that would consider a car’s capacity to avoid pedestrian collisions and mitigate injury in the event of a crash.

Warren’s bill, though, stands to nip those rollbacks in the bud — at least if it can make it out of committee. The Stop Corporate Capture Act would also build on Chevron’s past successes in several ways, including establishing an Office of the Public Advocate charged with facilitating public participation in regulatory proceedings and requiring rulemaking participants to “disclose industry-funded research or other related conflicts of interest.”

Perhaps most democratizing of all, the legislation would require an agency to respond to citizen petitions bearing 100,000 or more signatures.

“To tackle today’s most pressing challenges – including the climate crisis, growing economic inequality, and racial injustice – we need a robust, responsive, and inclusive federal regulatory system that works for the public interest,” said Rachel Weintraub.