Federal regulators just finalized a hard-fought vehicle safety rule that will automatically prevent drivers from striking tens of thousands of other road users a year — but because of the limitations of the technology and the regulation itself, the agency estimates it will only save about 360 lives out of more than 40,000 people who die on U.S. road each year, while leaving some of the most vulnerable among us at risk.

Vision Zero leaders on Monday celebrated the finalization of the new Automatic Emergency Braking rule, which will require U.S. automakers to continue to install on-board systems that stop light-duty vehicles before they strike another driver or pedestrian, and meet new, stronger benchmarks to ensure they work in a wider range of roadway crashes by 2029.

"[This rule] assures AEB is no longer a luxury feature reserved only for those who can afford it as optional equipment," said Joan Claybrook, former administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in a release. "This safety system is a proven innovation that should be hailed, honored and heralded.”

"Proven" though, doesn't meant "perfect" — and advocates stressed that far more needs to be done to protect the 99.2 percent of lives that automatic emergency braking alone won't save. Here are four fast facts to know about the new rule.

1. They'll have five years to do it

When the National Highway Traffic Safety administration first proposed this rule back in June 2023, it initially gave automakers three years to comply — which seemed pretty reasonable, considering that virtually every automaker voluntarily agreed to install AEB on their cars back in 2016. The final rule, though, gave car manufacturers an extra two years to continue to develop the technology to meet the agency's requirements, which include being able to reliably brake for a pedestrian after dark, when three out of four walking deaths happen.

And it sounds like automakers will need the extension. According to an Insurance Institute of Highway Safety test of 2023 model year vehicles cited in the rulemaking, just 11 percent of pedestrian automatic emergency braking systems "fully avoided the pedestrian mannequin in every test condition" — and only 17 percent were even able to consistently do it even during the day.

And even if automakers improve those stats in time, it will still take decades for older cars with older (or no) AEB systems to phase out of the fleet, especially if new vehicle prices continue to rise.

2. It won't help pedestrians hit at high — or very low — speeds

Another important change to the rule had to do with the specific speeds at which PAEB systems need to kick in— and at what speeds it's okay for those systems to fail.

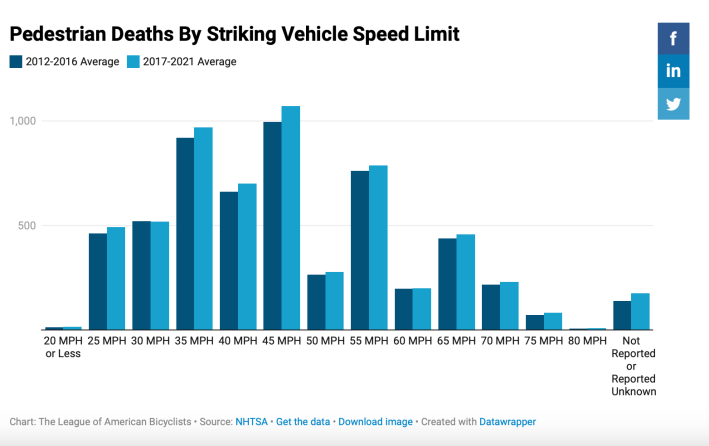

Unlike the initial proposal, which placed no upper limit on the velocities at which AEB needs to be effective, the final rule specifies that a system that can't prevent a vehicle-to-vehicle collision at 90.1 miles per hour or more could still be considered street-legal. And that upper bound drops to just 45.4 miles per hour for pedestrian crashes — which, disturbingly, is right around the single most common estimated impact speed in collisions where the pedestrian dies, and could be bad news for those hit by drivers traveling just a tiny bit faster.

The final rule also failed to drop the lower bound of AEB's speed requirements, too, specifying that the new systems only need to work at speeds over 6.2 miles per hour. That means that it won't prevent most of the slow-speed "frontover" crashes that are becoming tragically commonplace as the average American vehicle swells in size, making it particularly difficult for drivers to see small children who are sitting or standing directly in front of their wheels.

The advocacy group Kids and Cars has coined the term "bye bye syndrome" to refer the phenomenon of kids being crushed to death while wishing their caregivers goodbye in the family driveway.

3. Bicyclists, people who use assistive devices, and massive trucks still aren't included

Despite an outpouring of comments from advocates, the new AEB rule doesn't specifically include people who rely on equipment other than a car or truck to get around — including people on bikes, scooters, motorcycles, wheelchairs, and other assistive devices like walkers or canes.

To its credit, NHTSA specified that it wants to explore "additional pedestrian test devices outside of the child and adult pedestrian test mannequins, including those that reflect the broad diversity among the American public." But the agency says "the state of knowledge is not at the point where NHTSA can proceed with including" those groups, and it didn't want to hold off on initiating an initial pedestrian rulemaking "as a sound first step" while broader research is completed.

Also not included under the AEB rule are large trucks and heavy electric vehicles over 10,000 pounds ... but only because regulating them involves the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, with which NHTSA jointly proposed a separate rulemaking to cover those vehicles last year. News on that rule's progress is still forthcoming.

4. We can, and must, do more

As countless advocates pointed out when the rule was first proposed, automatic emergency braking isn't a silver bullet for our national roadway safety crisis, even if it's an essential tool to have in our belt. And as the fight for better vehicle safety tech marches on, they'll be pushing for things like automatic lane-keeping, driver monitoring systems, and Intelligent Speed Assist technology that countries in Europe require alongside AEB — but which weren't included in the current rule.

Perhaps more important, though, is that we continue to fight for better safety measures outside the vehicle, including those that get people out from behind the wheel completely by building communities where it is possible, safe, and even attractive not to drive.