America’s rapidly accelerating pedestrian death crisis is only part of a vast tapestry of suffering caused by traffic violence, a new report argues — and as the death toll climbs, so does the unseen anguish of victims, families, and communities.

In this year’s edition of its signature semi-annual Dangerous by Design report, advocates at Smart Growth America once again ranked the 101 largest U.S. metro areas by how dangerous they are for U.S. walkers, 7,522 of whom were killed by drivers across the country in 2022 alone.

That number, the report authors note, is at a 40-year high, and it's “roughly equivalent to the population of a small town like Buena Vista, Colorado, the student population of Gonzaga University, or more than three Boeing 737s full of people falling from the sky every month for a year."

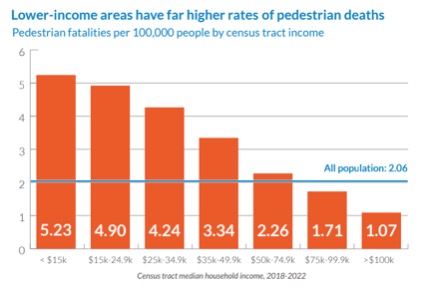

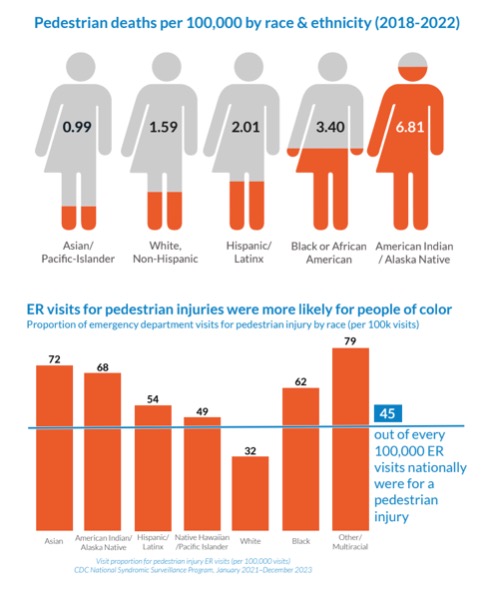

Those horrifying numbers won't come as a surprise to anyone who's been paying attention. Nationwide, pedestrian deaths have climbed or remained essentially flat every year for the last 15 years, skyrocketing 75 percent between 2010 and 2022. And year after year, low-income people, people of color, and elders have remained disproportionately likely to lose their lives.

Where these deaths occur isn't changing significantly either. Just like in previous editions of "Dangerous by Design," the majority (66 percent) of all fatal crashes documented in this year's report happened on state-owned roads like arterials, which combine deadly road design features like multiple fast, wide lanes with businesses and services that encourage people to walk.

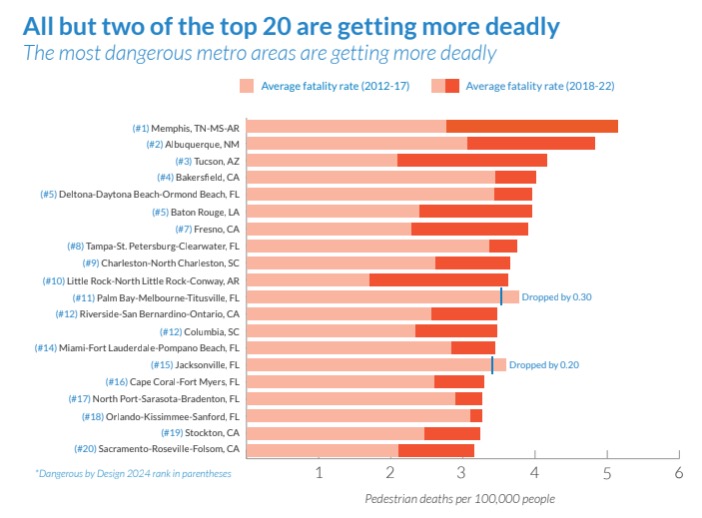

And because those dangerous roads aren't being re-designed to put people first, virtually all of the shifts in Smart Growth America's rankings have resulted from some U.S. communities simply getting deadlier faster than their peers, while few get safer at all. This year's most-dangerous metro — the region surrounding Memphis — unseated previous "champion" Daytona Beach, which fell to fifth place. But the already sky-high per capita pedestrian death rate still increased in both communities — it just increased more drastically in the Home of the Blues.

Meanwhile, even the "safest" metros on the list still aren't all that safe. The lowest-ranked region in America — the area around Provo and Orem, Utah — still had a higher average annual per capita pedestrian death rate between 2018 and 2022 than the United Kingdom had over the same period.

"Being the safest city in the most-dangerous nation does not give you bragging rights," said Beth Osborne, executive director of Transportation for America and the lead author of the report.

Osborne and her colleagues emphasize, though, that all this death is just the tip of the iceberg — and until policymakers take responsibility for all the harms that America's violent transportation system causes, they won't stop.

"The part of the culture that we should talk more about is the culture of elected officials and decision-makers who aren’t disgusted by the sheer number of people who are injured or killed as pedestrians," added Calvin Gladney, Smart Growth America's president and CEO. "At some point, these are decisions about where to allocate budgets, where to make investments, and when to say, ‘Enough is enough.’ We’re tired of teddy bears tied to poles; we’re tired of candles on sidewalks; it is just not acceptable for this many people die and to be injured."

Here are three less-discussed harms of America's roadway safety crisis that deserve more attention.

1. Grieving survivors

The 61,458 pedestrians who have died in car crashes in the last 10 years are staggering enough. If you multiply that number by all the friends and loved ones who are still missing them, though, it's almost unthinkable — unless you've experienced it first-hand.

One of those mourners is Beatriz Montano, whose 19-year-old sister, Corina Samuels, was killed in Fresno eight months ago. Because Corina was killed while crossing a street mid-block — the closest crosswalk, Beatriz says, was more than half a mile away — her family was denied assistance from the state's crime victim's compensation fund. Beatriz, meanwhile, has become newly aware of just how dangerous her community's roads are, and how easily her sister's life could have been saved if they were fixed.

"She was just walking to the store and crossing the street like we all do," Montano said during a recent press conference. "If there were crosswalks for her to cross the road safely … my sister would still be here with us."

As agonizing Montano's story is, it's only one of thousands upon thousands. The advocacy group Families for Safe Streets has mapped many of them — and vowed to continue to do so until their stories move policymakers to finally take action to bring deaths down to zero where they belong.

2. Serious injuries

For every pedestrian who loses their life in a car crash, many more sustain traumatic, often life-altering injuries. Exactly how many, though, is still an open question, since police departments don't always bother to document the non-fatal harm pedestrians' bodies sustain, nevermind track their severity.

One study cited by the "Dangerous by Design" authors found that between 2021 and 2023, pedestrian injuries resulted in a staggering 137,325 ER visits nationwide — but that data was reported by only about 80 percent of the nation’s emergency departments, so the numbers are even higher. Pedestrians who seek medical treatment after the crash, meanwhile, might not have their injuries counted as a "pedestrian" injuries at all — and if those injuries ultimately lead to death, they aren't always counted towards official roadway death tallies.

And just like they're more likely to die in a crash, pedestrians of color are also more likely to get hurt, with Black, Asian and Native American walkers all roughly twice as likely to be admitted to the ER following a collision than their white counterparts. And sometimes, those injuries lead to a lifetime of caretaking for their loved ones.

"We often don’t think about the fact that there are survivors, there are people who live on after someone is killed and after someone is injured," added Gladney. "It’s not just the sheer calamity of the number of people who are killed and people who are injured; it’s all the stories, and the real people behind those stories."

3. Trips not taken

Of all the things U.S. walkers collectively lose as our road network gets more violent, perhaps the hardest to measure are the trips we don't take — and the opportunities they miss out on because of it.

"Millions of potential walking trips don’t happen because of the very real dangers and inconveniences presented by the safety and quality of nearby streets," according to "Dangerous by Design."

And while some of those trips might be replaced by journeys on other modes, they're often forgone completely, especially among those for whom driving is not an option because of a disability, age, immigration status, criminal record, or because they simply can't afford to maintain an automobile in a car-dependent community with poor transit and bike infrastructure.

And as more people are functionally forced to give up walking in their neighborhoods out of fear of violent death or serious injury, the pedestrians who remain lose the safety in numbers they might have enjoyed with more people around — as well as the opportunities, experiences, and physical, mental and social health benefits that come from interacting with their communities with no windshield in the way.

The good news? With well-known road design and policy changes to keep people safe, communities can recover the pedestrians they've lost. First, though, policymakers have to take a stand for what's right — and advocates have to hold them to a higher standard.

"As a culture right now, [we’re saying], ‘There’s some acceptable number of people being hurt while pedestrians, and we’re just not going to do anything about it,’" added Gladney. "We really need to figure out how to raise the ire and say, ‘Enough is enough’ — and as an elected official, [no one should] just be allowed to say, ‘Well, this isn't something that I can deal with.’ [We need to be] part of a movement that pushes decision makers to do things differently."