A top international transportation organization is laying out exactly what makes a bus rapid transit system great in our rapidly-changing world — and why so many in the U.S. aren’t measuring up.

Late last month, the Institute for Transportation Development and Policy released the newest edition of the Bus Rapid Transit Standard, which since 2012 has set the bar for exactly how BRT should be designed and run to maximize its benefits for riders — and ranks which cities are clearing that bar in 2024.

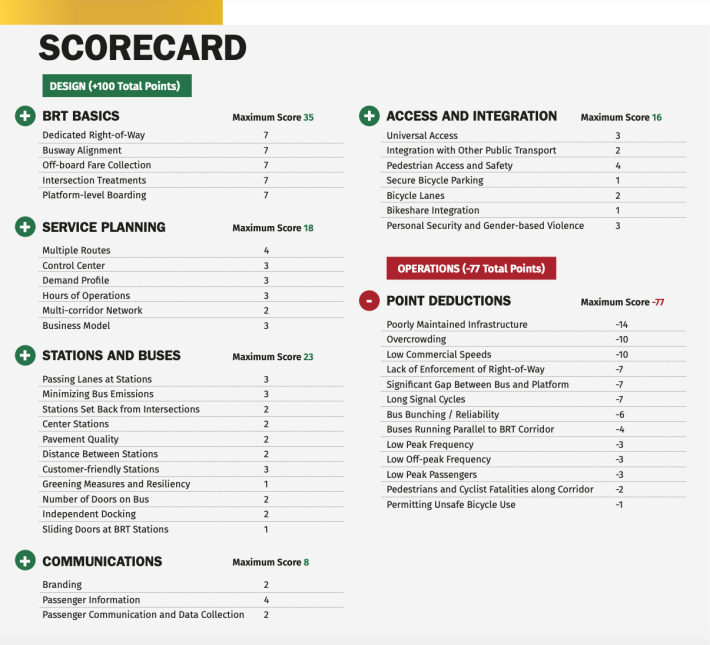

Though laymen might assume that “BRT” is synonymous with any old bus lane, the Institute says actual BRT must meet a few crucial requirements that guarantee lines will operate as quickly as possible — and many BRT-esque systems, like New York City’s Select Bus Service, don’t qualify. Specifically, true BRT has to give buses not just their own lane, but at least a couple miles of separated and protected lanes that drivers can’t easily enter; operators also have to align those lanes in such a way that drivers are only rarely allowed to cross them, like in the median of a road or on a dedicated two-way busway, guaranteeing that buses can run nearly as fast as light rail at a fraction of the cost.

Moreover, to even be eligible for ITDP’s best-BRT rankings, operators have to incorporate at least a few other basic design elements aimed at speeding vehicles, like off-board fare collection so passengers aren’t caught fumbling for change at the door, and boarding platforms raised to the level of bus doors, so passengers can walk or roll straight on with assistive devices or strollers.

And the best-of-the-best systems score highly on hundreds of sub-categories, which assess such things as the providers’ underlying business models, how well the lines integrate the local sidewalk network, or whether buses arrive on time.

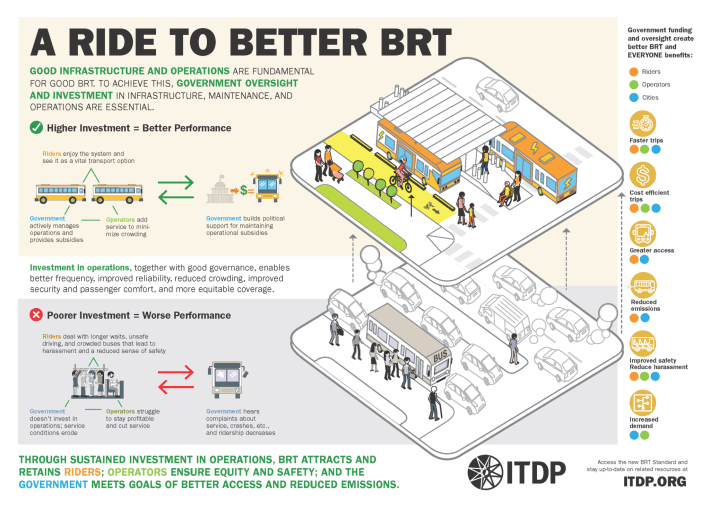

Defining great BRT at that granular level of detail, Institute officials explain, is becoming even more important as the model explodes in popularity — and as some communities dilute the game-changing concept in response to pushback from drivers.

“There's been a lot of slipping and sliding, especially as the political decisions became more difficult,” said Aimee Gauthier, chief knowledge officer for ITDP. “Suddenly BRT wasn’t always operating in dedicated lanes, because it was too hard, politically, to take that space from cars. And so that was part of the point [of the standard]: to make sure that when you when you're talking about bus rapid transit, you really get to the heart of what ‘rapid’ is, and really understand what things are going to make the bus system work better for people.”

The 2024 edition of the standard also seeks to get to the heart of what BRT should be besides just "rapid": namely, green, equitable, healthy, and accessible to people of all demographics. The new edition has been updated to factor in things like whether staff is trained to address violence and sexual harassment on board, and whether stations are designed to mitigate flooding and urban heat island effects, rather than adding ever-more asphalt to ever-warming cities.

Systems can also lose points for things like overcrowding, which has become a particularly big deterrent to ridership since the dawn of the pandemic.

“You can't solve every cultural problem with a transit system,” adds Gauthier. “But there are ways that you can build in safety into your design and use public transport as a platform for where you want to go as a culture, and as a society.”

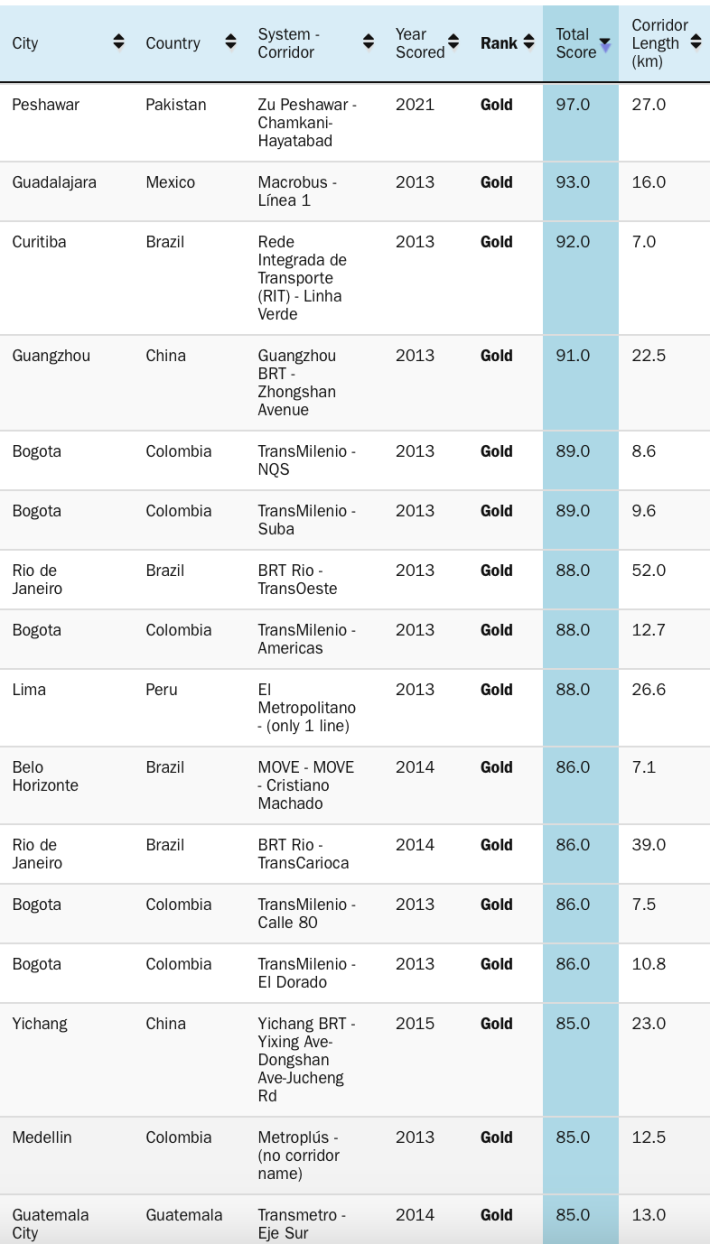

Some of the communities that ranked highest might come as a surprise. The single best BRT line in the world is in Peshawar, Pakistan, which claimed the title thanks in large part to a “gender audit” that prompted the agency to radically transform its corridor explicitly around the needs of women. A line in Guadalajara, Mexico came in second, thanks in part to its excellent connectivity with the local active transportation networks — something Gauthier says nearly every American system on the list struggled to accomplish.

A line in Curitiba, Brazil, which is widely credited with launching the world's first BRT system way back in 1974, came in third, and nearly 40 percent of “gold”-ranked routes belonged to Bogotá’s famous Transmilenio system, which popularized BRT in the early 2000s.

Meanwhile, only two U.S. lines — one in Hartford and another in Cleveland — earned “silver” status, while six others earned “bronze” or “basic.”

None earned gold.

Gauthier emphasized, though, that simply making the rankings at all is an "amazing" achievement, and that she’s thinks the U.S. is on track to become a global BRT leader — if it invests the money and energy it needs to do better. And she also adds that many of the metrics the Institute outlines can serve as a blueprint to make other kinds of transit great, too.

“The level of dignity that people have when using bus systems is pretty low right now,” she added. “You have to wait for a long time, often in an unattractive, terrible places. And if they were able to dignify that experience just a little bit more, that would be great. … Transit is the cornerstone of the solutions we need for our changing world. The BRT standard elucidates that.”