Editor's Note: A version of this article originally appeared on NEOTrans and is republished with permission. We thought it was a fascinating example of what may prove an emerging trend across the country: private rail operators competing with Amtrak for new routes.

Last week, two things happened in the rail world that are probably related. They have been brewing in the background for a while, but they finally appeared in public almost simultaneously. Federal corporation Amtrak and private-sector company Brightline showed their hands that they may compete for Ohio passenger rail expansions and real estate developments. And Cleveland may end up the winner.

First: Amtrak revealed in its fiscal year 2025 budget request to Congress that it wants a five-year, $300 million Great Lakes Station development program. Amtrak specified it wants to enhance stations between Cleveland and Chicago, starting with $25 million next year for environmental permitting and blueprints. In Cleveland, Amtrak is working with community officials to plan for a multimodal transportation hub on downtown’s lakefront.

The program will allow Amtrak to partner with communities to build infrastructure necessary so trains can board passengers from either side of Norfolk Southern’s (NS) two main tracks. Not only will that reduce delays to NS’s 70 daily freight trains from Amtrak no longer having to slalom between them to board passengers at single-platform stations, it will also speed up Amtrak’s four nightly passenger trains — and allow for daytime expansion.

Nearly 2,000 miles away in Las Vegas, NV, meanwhile, dignitaries pounded in yellow spikes into a section of track, commemorating the start of construction of Brightline’s $12 billion, 200-mph high-speed rail line linking Sin City to Greater Los Angeles, namely Rancho Cucamonga.

Immediately after the ceremony, Brightline Founder/CEO Wes Edens and U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg were asked by Forbes reporter Alan Ohnsman to discuss the economic benefits of adding high-speed rail to a 270-mile route that’s too long to comfortably drive and too short for airlines to economically serve. The resultant increased travel, consumer spending and the construction plus permanent jobs may be significant. But that’s not all.

“It’s going to open up the floodgates for American expectations around high speed rail,” Buttigieg said. “It won’t anymore be ‘I just got back from Japan — why can’t we have that?’ It’ll be ‘I just got back from Vegas — why can’t we have that in the Midwest or the Northwest or wherever I live as a domestic tourist in the United States?’ This is important because it establishes it can be done here. Which, by the way, of course it can done here. This is the United States of America. But in the past we haven’t invested enough to make this happen.”

But where in the USA could the next copycat emerge? Edens was asked by Ohnsman about that. He discussed several regions of the country he was considering. Edens mentioned the Texas Triangle — Dallas-Houston-San Antonio/Austin. In the Pacific Northwest, he pointed to Seattle-Portland. And in the Midwest, there was a route on the tip of Edens’ tongue.

“In the Midwest you have places like from Cleveland to Columbus and whatnot,” he said.

The “whatnot” hopefully refers to continuing the 3C&D route connecting Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus and Dayton to link four of Ohio’s largest metro areas in 255 miles, as has been considered for a long time. Several other routes have also been pursued before and are being considered again now.

But one of the hangups for Ohio’s elected leaders was the Amtrak approach, which under federal law requires a state government to take the initiative — make the capital improvements to tracks, stations and acquire railcars, then purchase passenger rail service from Amtrak to run the trains. Ohio has been unwilling, saying it doesn’t want to build and operate a passenger rail system.

Such was the case in Florida too. Which, like Ohio, the Sunshine State gave back federal money during the Obama Administration. In fact, it gave back more — $2.4 billion for high-speed rail between Orlando and Tampa. Ohio gave back $400 million for 79 mph Amtrak trains linking 3C&D, plus planning money to speed it up to 110 mph. Brightline offered a political solution palatable to Florida, one that might work in Ohio: “We’ll finance it, build it, and operate it. We just need some highway rights of way and station funding.”

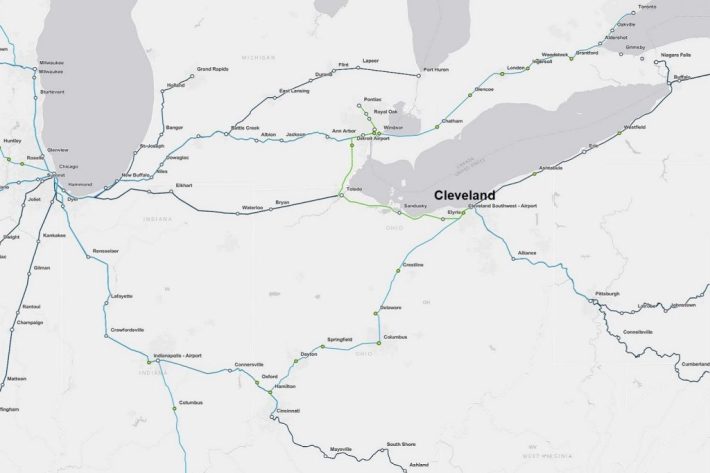

NEOtrans has learned from a source familiar with Brightline’s goals that company officials are interested in more than just 3C&D. They’re also very interested in Chicago-Fort Wayne-Columbus. And several years ago, the company issued a national map of potential routes of interest to Brightline. Among them was an upside-down T, three-routes-in-one matrix of Cleveland-Chicago, Cleveland-Detroit and Detroit-Chicago with Toledo as the hub.

In summary, Edens says he is looking for routes with population centers at both ends connected by an underutilized but well-engineered railroad right of way that can accommodate train speeds of up to 110 mph. Or, if demand warrants, they’ll pursue a relatively flat highway with gentle curves and a median or an undeveloped flank where a high-speed railroad can be built to offer speeds anywhere from 125 to 200 mph.

These assets came into play for Brightline’s first route linking downtowns in Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach with Orlando International Airport. In a few years, construction could start on an extension to Tampa using the median of Interstate 4. Brightline wouldn’t have to grade a right of way or construct roadway overpasses and it could get a good property deal from the Florida Department of Transportation like it did alongside Highway 528 from Cocoa to Orlando.

Edens was inspired by reading about Henry Flagler who joined John D. Rockefeller and Samuel Andrews in Cleveland in 1867 to form Standard Oil. But Flagler is perhaps best known as the founder of the Florida East Coast Railroad which also developed resorts, hotels and other real estate along its tracks. That offered a politically palatable solution for Florida to support it today.

Edens is applying modern railroad-real estate synergies with Brightline, owned by Florida East Coast Industries which also develops and owns real estate. That includes 2 million square feet of residential and commercial high-rises at Brightline stations with more planned. All are owned by Fortress Investment Group of which Edens is co-CEO with Peter Briger. Historically, real estate and transportation have had a strong, synergistic relationship.

In Downtown Miami, Brightline built a new Central Station topped by three high-rises and served by the MetroRail rapid transit along with the free-to-ride MetroMover downtown automated people mover. At the other end, the state of Florida funded a new terminal at Orlando International Airport for Brightline trains, an extension of the airport people mover and 19 airplane gates. Miami-Orlando trains carry 8,000 riders per day and growing.

In Las Vegas, Brightline acquired 110 acres of land near Harry Reid International Airport for a train station/real estate development. Near Victorville, CA, it acquired 300 acres for a station and development that could accommodate a link to the California High Speed Rail that’s under construction to the Bay Area. Stations will also be located at Hesperia and Rancho Cucamonga. Brightline’s high-speed tracks will be built in the median of Interstate 15.

“We’ve been contacted by a lot of different governors and whatnot that are curious about this,” Edens said. “I think today (LA-Las Vegas groundbreaking) is a real milestone to see that this is a reality that is now happening. I think there could easily be a handful of these that could turn into real projects from our standpoint in the next 12 to 24 months. It’s an exciting time for us.”

The 12-24 months comment likely refers to the time necessary to conduct Service Development Plans for more than two dozen routes to which the U.S. Department of Transportation awarded funds in December 2023. Four Ohio travel corridors were among them — Cleveland-Columbus-Dayton-Cincinnati, Cleveland-Toledo-Detroit, Pittsburgh-Columbus-Fort Wayne-Chicago, and New York-Washington-Cincinnati-Chicago.

“For those who say this isn’t Europe, that’s true — it isn’t Europe,” Buttigieg said. “We’re doing this on American terms. What we definitely have in America are these kinds of geographic layouts where you’ve got lots of city pairs that are an uncomfortably long drive or an inefficiently short flight apart from each other. Those are excellent candidates for high-speed rail.”

Service Development Plans are the first in a series of increasingly detailed planning steps to identify the best paths for linking city pairs and later, to conduct detailed design and environmental permitting for those paths. Ohio has a mix of underutilized railroad rights of way and highway medians Brightline could affordably lease or acquire to gain hundreds of miles of routes with the stroke of a pen.

Without spending big to get to Downtown Cleveland, Chicago and 3C&D trains could terminate at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, as Brightline does at Orlando’s airport and will do near Las Vegas’ airport. Cleveland’s airport has something they don’t — a rapid transit rail link to the region’s two largest employment centers, Downtown Cleveland and University Circle.

At Brightline’s Florida speeds, Clevelanders could travel to Columbus in 100 minutes, to Detroit in 2 hours and 15 minutes, Cincinnati in three and a half hours and downtown Chicago in four and a half hours. Travelers will enjoy stations and trains that are modern, clean and bright with creature comforts, has at-seat charging ports, tasty food and beverages, strong/free Wi-Fi and first-class accommodations. And the employees are customer-focused.

Boarding at a site on the east side of Cleveland’s airport could soon be accompanied by a major mixed-use residential and entertainment district. That’s where Cleveland Browns owner, the Haslam Sports Group, is considering building a domed stadium and hundreds of thousands of square feet of high-rise residential, hotels, retail and restaurants.

Brightline CEO Edens also is the majority owner of the Milwaukee Bucks. The basketball team’s minority owner is the Haslam Sports Group. Perhaps Edens is already chatting up the Haslams about his ideas?

Those billionaires can do what Amtrak legally cannot — lobby elected officials. Much of public policy is driven by campaign contributions. So while Amtrak is promoting a worthy cause of improving train stations along its Northern Ohio route, possibly to get ahead of Brightline, Brightline may roll out the gravy train in Columbus to pass Amtrak on the fast track to Ohio.

It should be noted that both companies’ efforts aren’t mutually exclusive and can simultaneously serve some different communities and travel markets. And if both vie for the chance to invest along their routes, in this competition, Cleveland could well end up the winner.