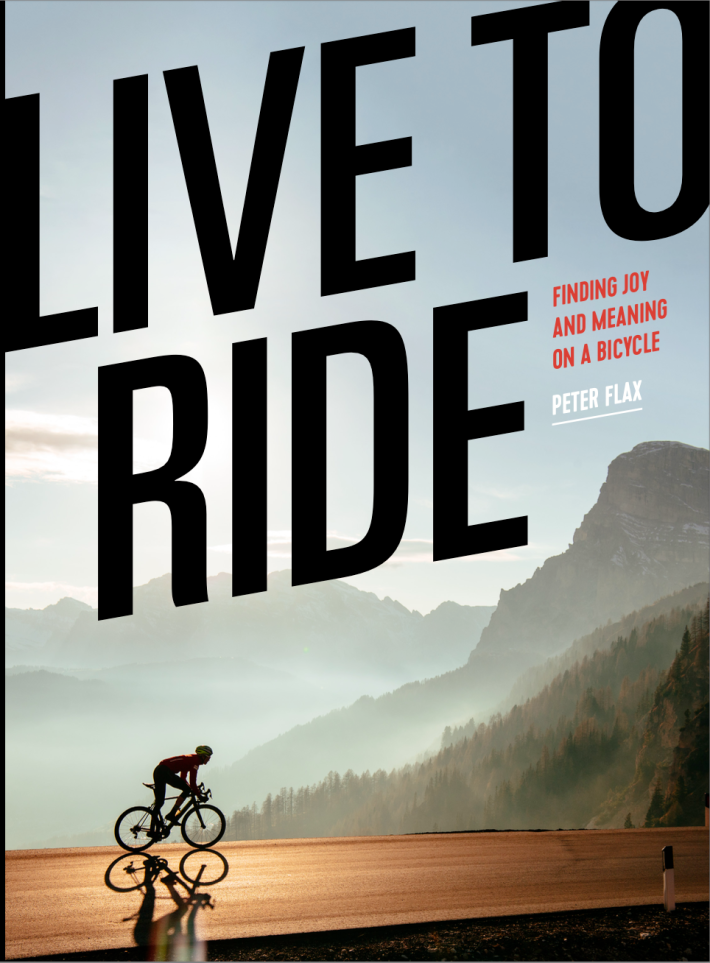

If there is one person who embodies the sport, passion, utility and exhilaration of cycling, it is Peter Flax. He's not only been pedaling around since growing up in the New York suburbs, but as a longtime bike writer and the former editor of Bicycling, he's occupied a lofty perch from which to give a "State of the Cycling World" address, which he's more or less done in his new book, "Live to Ride: Finding Joy and Meaning on a Bicycle" (Artisan, March 19, 2024). It's a visually arresting overview of all the different tribes that make up the cycling family — and how there is strength in our diversity ... if we use it. Flax chatted with Streetsblog's Gersh Kuntzman from a hotel room in Philadelphia.

An audio version of this conversation will be posted soon wherever you get your podcasts. This version has been edited for clarity.

Peter Flax: I'm excited to be here because I have been a longtime fan of Streetsblog. I just feel like your outlet is a really important voice in bike culture.

Gersh Kuntzman: Let the record show that I did not tell him to say and that he's not compelled to say that, but I appreciate it. So let's just start with the big thesis of the book, which is basically that all of us riders have more in common than we might realize when it comes to addressing bicycling's place in society. It's hard for me to get my head around that because I don't even really think about other cyclists when I'm on the road; I'm thinking about car drivers, and they're the worst. So explain to me what your what you mean.

Peter Flax: This is an idea that came to me slowly over the last decade. And I think that historically, riders have looked at themselves as part of some kind of bike subculture — that they're an urban rider or a mountain biker or a fitness enthusiast and didn't see everybody else who rode bikes as having a lot in common. The experience for me of moving to Los Angeles and transitioning from someone who was a racer and recreational rider to someone who was kind of a full-time utility rider, made me realize that we all do have way more in common than we might might realize. And then also just the importance and value that if everyone who rides, fees that interconnectivity, how much we can all gain gain from that.

Gersh Kuntzman: OK, but what are we going to gain? So what are we going to do with that knowledge that we have a lot in common?

Peter Flax: I've seen that bike racers, even pro racers and fitness enthusiasts, get involved in advocacy because, like all of us, their rides start from their front door. And one thing that everyone who rides shares is this feeling of, "Jeez, I'd really like to get home from this ride alive and not get terrorized."

And so, almost everybody in one way or another is getting on the road, and there's a certain kind of utility riding now that almost everybody does. In the past, a lot of the enthusiast community didn't give a crap about the issues that a rider like you cares about that. [Now,] everyone's more tuned into it. The more people that ride on city or suburban streets, the more people that become attuned to how bad infrastructure and the laws and police enforcement and driver education are — those that are all going to be positives for utility riders. I do think that having utility riders feel that other kinds of riders are our brethren and vice versa is just going to make the whole experience more positive.

I definitely see a lot more interconnectivity happening. And now, I'm hoping this book is something that people in all those communities read and, in some small way, shift the needle towards greater collaboration.

Gersh Kuntzman: I agree with that. But even when we speak with one voice, even in New York City, where half of the households don't even have access to a car, we are still seen as some sort of weird, freakish alternative transportation. Look at Los Angeles, where cyclists came out in favor of a bunch of legislation that went through, despite objection from firefighters. It all combines into the image of cyclists as the bug at the picnic that everybody wants to swat away, even when we speak in that common voice. So can we get past how car culture dominates our life these days?

Peter Flax: That weighs on me heavily. The first answer I'd have is that while we still collectively remain a minority that a lot of people don't understand or relate to, our voice is stronger when we're all together than if we're all in little subcultures. And in this book, my tack was to be relentlessly positive with the idea that there's this potential that maybe you and I can't see until everyone comes together. That legislation you mentioned in LA is a really great example — to see that two-thirds of Angelenos, including tens of thousands of people who don't rely on a bike for daily transportation, allied with riders and pedestrian advocates to make our city safer. And so it's like all sorts of positive things are possible, right?

Like, you can go on vacation to Paris now and see how that city is reshaped. Even if you're not a rider, you can go like, "Oh, this is how it would be if the streets are given back to people getting around." Other modes could make my city better in ways that I didn't even think about. And so I'm hopeful for this sort of unseen positive stuff that can happen down the road as a benefit of everyone getting together.

Gersh Kuntzman: The funny thing is, for vacation, a lot of Americans go to Europe, where whole sections of the urban core are pedestrianized. Or they go to Disneyland, which is the flipside of that, but still no cars and you walk around everywhere. And when people think about the greatest days of their lives, it's when they were back at the old college, where, you know, the campus is built on a very livable scale with no cars in the core. And it's always so funny to me that all our lives, we try to connect to those car-free spaces, and yet when we actually develop our cities or organize our lives, that's the one thing we neglect.

Peter Flax: As someone [who gets] to travel a lot for work, every time I visit big American cities, I just think about how it's incrementally better for riding and walking than it was the last time I was there. Things are moving in the right direction, almost everywhere. And it's really frustrating that it's not happening faster. This will actually be a place where everyone will jump on bike share, to go to a lunch a mile from where they are and they won't have to worry at all of getting hit. It's just not happening as quickly as it should, given the importance.

It always just strikes me as being similar to America's gun problem where the solution is just so obvious. And just to get everyone aligned, to take the steps that [are] going to reduce the carnage ... it's going to require decades to accomplish. If you do get around on foot or on a bike for the majority of the time, it's really frustrating.

Gersh Kuntzman: Your book specifically says — and I'm going to quote you to you here — "There's no prescriptive advice for making riding safer or polemics on why bike culture is so often maligned by outsiders. It's more of a celebratory work of covert advocacy, founded on my confidence that many positive things will happen as everyone who writes, absorbs, and accepts the interconnectedness we share." And then you recently tweeted, "Cars are like a cult for some people." So can you connect those thoughts for me?

Cars are like a cult for some people. pic.twitter.com/cUYrgK2o2z

— Peter Flax (@Pflax1) March 2, 2024

Peter Flax: In terms of cars being a cult for some people, everyone who rides or walks sees this plain as day: so many decades and trillions of dollars have been put into making cars the de facto way to get around. So for a lot of people who primarily get around in a motor vehicle, they just can't even perceive the carnage, the environmental damage, the quality-of-life [issues] they cause, and how it impacts everyone else. [These are] people who just can't even imagine alternative ways of looking at transportation and urban planning. And, so they just start saying riders are just in the way, or [they're] an entitled minority trying to fight them for valuable space when they're this overwhelming majority. And it's extremely hard to debate with folks.

But on the covert side, if we get more people to ride and people from all corners of our culture to get involved, then it gives us more power and more numbers. There have been so [many] polemics about e-bikes and how they fit into our culture. And I know a lot of existing riders who have felt really negative about them. But in general, people [are] getting out on the road; more people [are] suddenly noticing that the infrastructure sucks; people [are] noticing how many people are driving distracted and playing with phones while they drive; and [people are] noticing that the cops are more interested in hassling them [than] the people doing stuff in 5,000-pound vehicles.

The bigger this block of passionate people wanting to use bikes to get around, [the more] it collectively provides muscle for people that have this common ground of thinking [that] biking is just a great way to get around. That it's utilitarian and fun, and that we need our cities and our government and our law enforcement and our legal systems to evolve so that the activity is safe like that. That's the covert side.

Gersh Kuntzman: People have been biking for a lot longer than people have been driving. Yet the mass bike culture didn't really develop, and it's obviously because the car industry has spent trillions over the last 120 years to ostensibly make invisible most of the harms of driving. They did it with pedestrian deaths by blaming the pedestrians. And they do it with pollution and congestion by showing these commercials with not a single cloud in the sky and not a single other car on the street. It's gotten so that even the most enlightened driver doesn't see the invisible harms of driving. So when I got to that line in your book, "It should not take years to feel like a real cyclist," I focused on the reason that it takes so long for a lot of people to feel like a "real cyclist" is simply because it's so needlessly unsafe because of cars. So maybe that's a good sort of way to conclude this interview: why does it take so long to [feel like] a real cyclist?

Peter Flax: You know, in LA, there's probably hundreds of thousands of people who have a bike and they'll like ride to the beach and ride on a path or they'll go to a park and ride in the park. But the idea of riding from wherever they live to Starbucks is terrifying to them because the mile between their house to the coffee shop is scary. And so a lot of people feel like [a] mere occasional hobbyist because of those issues, and they feel like other people they may meet are, like, real riders because they're experienced or brave enough to get out there. I would obviously like to just blow that up, but just saying, "I want Olympic Boulevard to be safer" isn't going to make it so. So part of that is going to require advocacy and time and this ongoing battle that Streetsblog is at the forefront of.

And part of what I hope the book does to some small extent is just communicate the importance of thinking about how, when you pass someone on a city street who is wobbling on a bike share bike, they're your brother or sister right there. We are on the same team.

"Live to Ride: Finding Joy and Meaning on a Bicycle" (Artisan Books) will be out on March 19 anywhere books are sold.