Some mid-sized cities are struggling to deliver bus shelters to the marginalized neighborhoods that need them most, according to a new study that also suggested a new method by which agencies and advocates can identify other ways to make our transit networks more equitable.

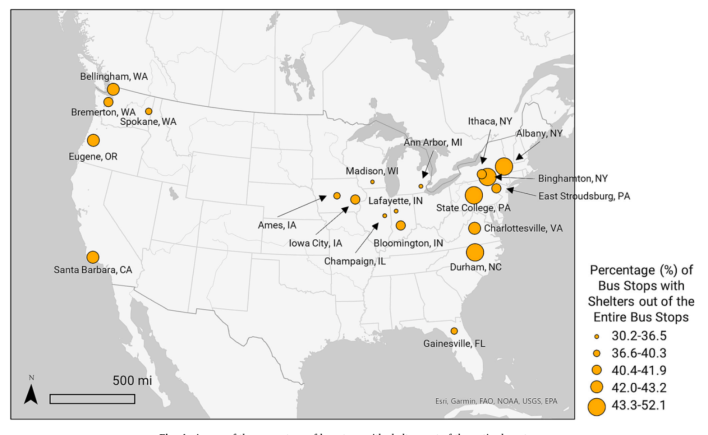

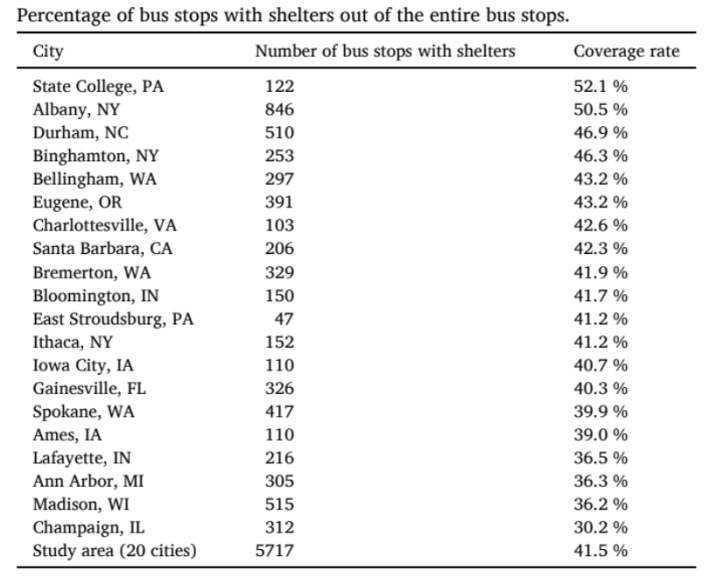

Researchers at Virginia Tech used the power of AI to rapidly map the distribution of bus shelters in 20 cities across the U.S., with a focus on medium-sized communities with high bus ridership but few resources to maintain up-to-date inventories of their stops. And in too many places, that lack of resources can leave riders with downright sorry places to wait, and advocates with little data on how their networks measure up to their peers, short of calling up other agencies one by by one or scouring Google Street View images manually.

"In the US, there are some bus stops where it's hard to even tell if it’s a bus stop or not, because it’s just a metal bar with no shade or benches," said Junghwan Kim, the director of the Smart Cities for Good research group and the lead author of the paper. "Previous behavior studies show that having more amenities really positively affects the utility of people’s trips — but data [on the prevalence of those amenities] just isn’t available."

Here's the good news: Of the 20 mid-sized cities on the researchers' list — which, perhaps unsurprisingly, was dominated by college towns — nearly all (18) did a solid job of concentrating their shelters in areas with a high population density and lots of likely riders.

In four cities, though — Ames and Iowa City, as well as Durham, N.C. and Bellingham, Wash. — agencies were less likely to provide shelters at stops in neighborhoods of color, whose residents are statistically more likely to rely on public transit to get around than their white counterparts. And because the absence of shelters can actually make wait times feel longer and decrease overall ridership over time, that has big implications for transportation equity.

"[Communities of color] are the ones who really need the bus," said Kim. "Having more bus shelters and good bus shelters would benefit them a lot. And when there are cities that have fewer bus shelters in minority neighborhoods, that’s a problem from a mobility justice perspective."

Meanwhile, even the best-sheltered cities on the list were only able to offer awnings to about half of stops, with the worst offering them to roughly one-third.

Kim is careful to note that he "in no way" intends to "blame" those agencies for their lack of equitably distributed shelters, and that he hopes his research can be a "starting point for conversation" about the structural reasons why so many agencies struggling to deliver even the basics. And if technology can help amass and analyze better data about bus stops across the country, it could help agencies and advocates fight to increase funding streams to improve them — and someday, put a shelter at every stop they feasibly can.

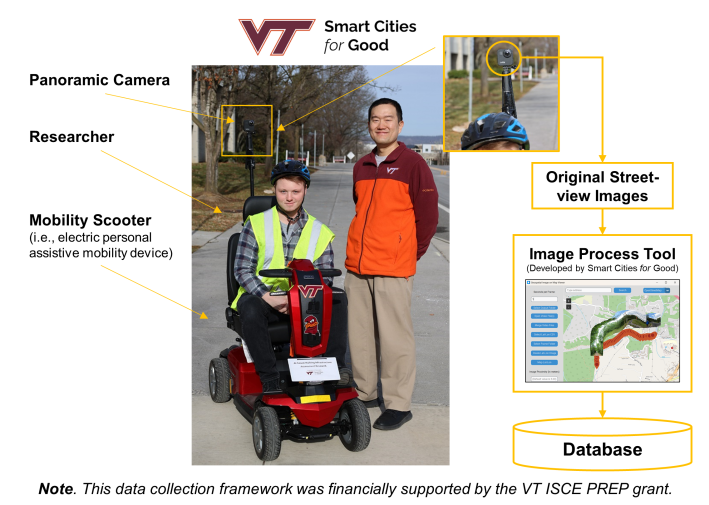

Eventually, Kim hopes that machine learning can help identify other opportunities to improve bus stops, too — especially as the images that AI learns from continue to improve. While the bus shelter study relied on Google images taken by car-mounted cameras, he's developing a scooter-mounted camera system that can safely mingle on the sidewalk with pedestrians, and get detailed information on opportunities to transform sorry bus stops into superb ones.

"[We need to talk about] other factors, like whether there are benches or not, garbage cans or not, lights or not, good signage or not," added Kim. "Eventually, we want to develop a more robust and comprehensive deep learning model to incorporate many factors of the bus stop experience."