Editor's note: this article originally appeared on the New York Civil Liberties Union and is republished with permission. We share it as an object lesson to other U.S. communities considering comparable highway cap projects.

Beginning in 2018, the NYCLU and its supporters began sounding the alarm about the I-81 construction project in Syracuse. More than 50 years ago, the construction of the I-81 viaduct in Syracuse destroyed the Black working-class community known as the 15th Ward, displacing thousands of residents. In the late 2010s, the state produced plans to tear down and replace the viaduct, but there were serious flaws with the NYSDOT’s proposal.

Community advocates, along with groups like the NYCLU were eventually able to significantly improve the state’s construction plan. But now another highway project, this time in Western New York, raises similar red flags.

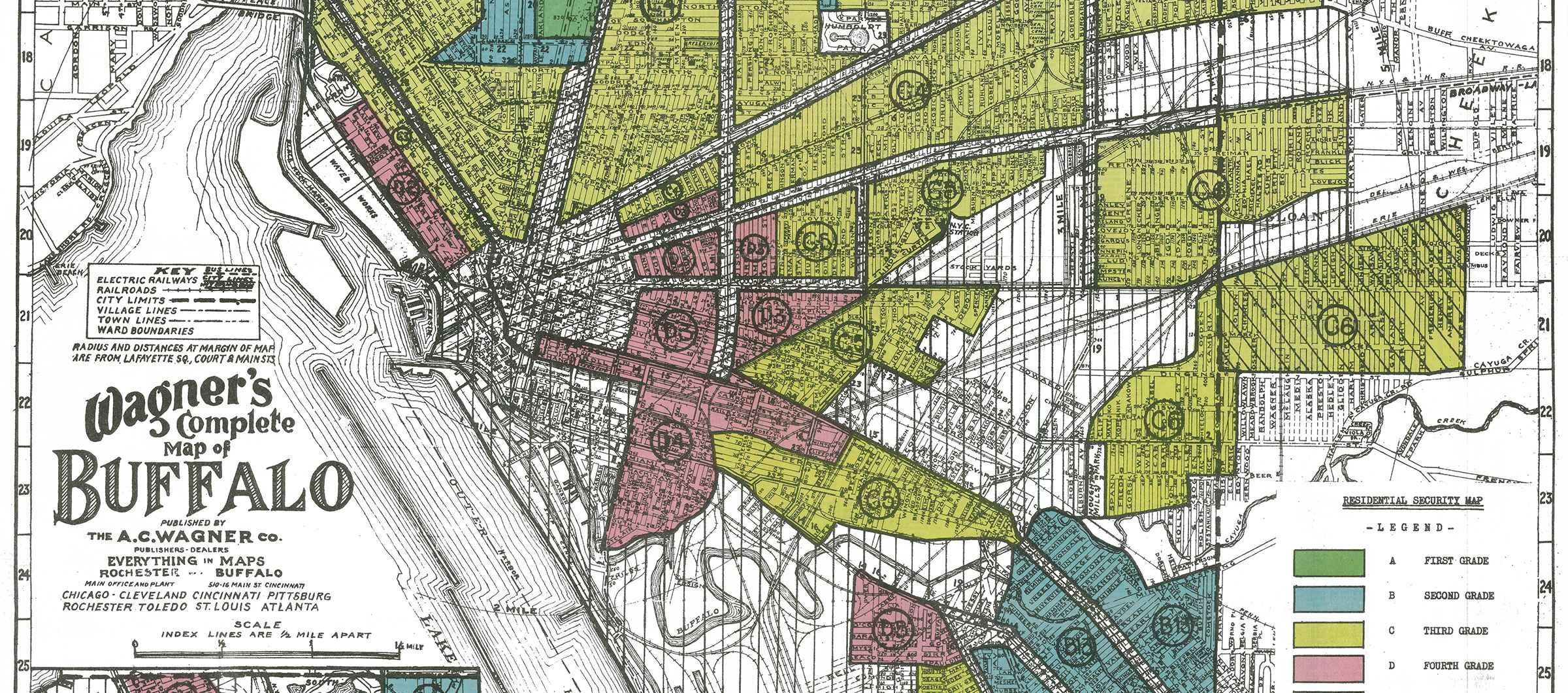

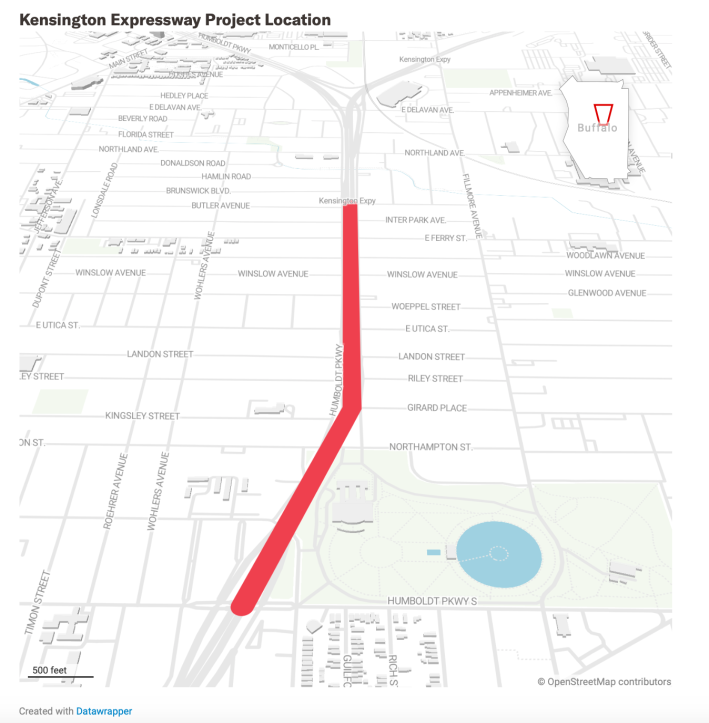

The construction of Buffalo’s Route 33 – known as the Kensington Expressway – in the 1960s ripped through and displaced an almost entirely Black neighborhood. Construction of the Kensington Expressway separated neighborhoods by race and class and demolished thousands of homes and businesses.

Property values in the neighborhood closest to the Kensington plummeted and they remain among the lowest in the city. The lasting impacts are felt today as many residents cannot benefit from the generational wealth that’s usually built through homeownership.

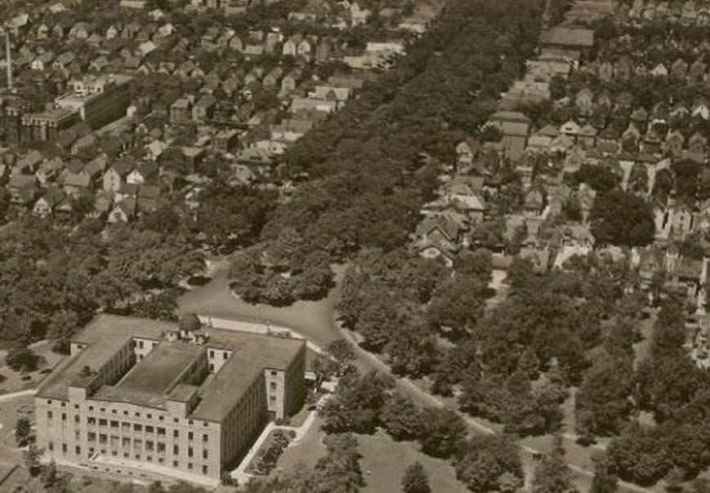

The severe economic downturn created by the original construction isn’t the only legacy of the Kensington. It has also cut people’s lives short. Black residents in the area have some of the highest rates of asthma, respiratory disease, and premature death, in large part because of the Kensington’s endless stream of pollution. The construction also destroyed the Humboldt Parkway, one of the most beloved greenspaces in New York State at the time.

These conditions are an all-too-common example of environmental racism, in which governments force low-income people – who are often people of color – to endure the burden of heavy pollution. Meanwhile whiter suburban communities reap the benefits of easy and quick access in and out the city. In this case, the Kensington was built in part so that white people could flee Buffalo for the suburbs, where private investment in businesses followed.

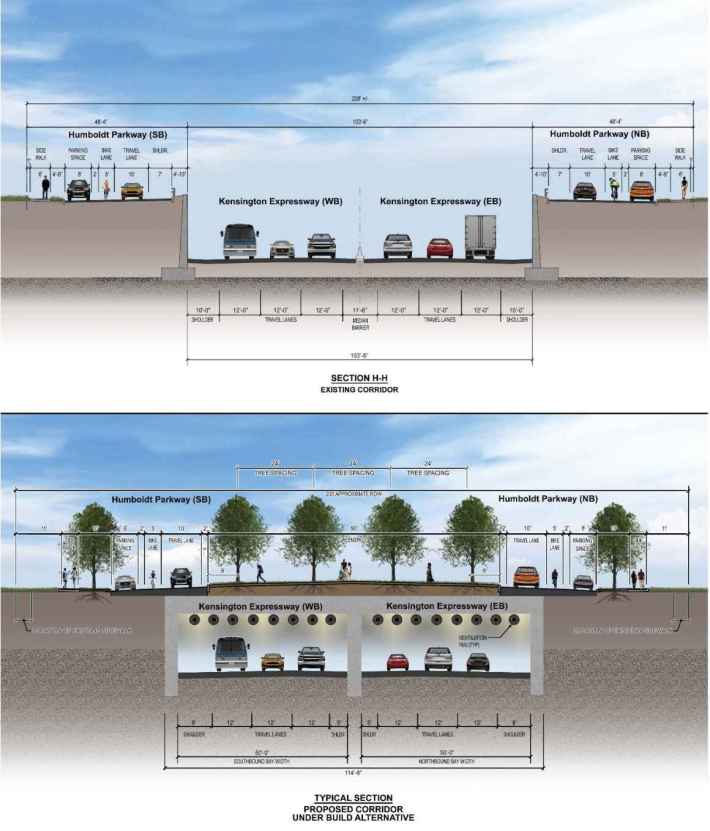

Now, six decades after the Kensington Expressway was completed, state officials are promoting a redevelopment plan that would create a “cap” over one portion of the Kensington. The so-called ”cap” would create a concrete surface on top of the highway that would enclose this portion of the highway, turning it into a tunnel. The tunnel would be covered with three feet of soil, on top of which eleven acres of grass, trees, and other green space would grow.

There’s one major problem with this proposal. By trapping the pollution inside the tunnel, air quality would be made worse for the predominantly Black people living near the tunnel entrance and exits where the pollution would ultimately be released. This Black community already has increased incidents of asthma, cardiovascular disease, and premature death. Now these residents who live, work, or attend school near the tunnel’s entrance and exit will have to shoulder even more air pollution. Rather than addressing environmental racism, this project has the potential to make it worse.

The state claims the plan will reconnect neighborhoods that were broken up by the original construction while also increasing the amount of greenspace in the neighborhood. But the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) has done little to determine what the full scope of negative impacts of the project will be on those living closest to the construction site. And right now, there are more questions than there are answers.

Residents of the neighborhood, local community partners, and advocates have been asking for more information on the potential impacts of the tunnel. If the NYSDOT produced an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), which is standard practice for all major construction projects, those answers could easily be provided.

The NYSDOT avoided conducting an EIS by claiming it completed a “robust environmental assessment.” But this “assessment” is something that has no definition and very little meaning. It also allows the NYSDOT to decide what impacts of the project to look into – unlike an EIS that requires the NYSDOT to examine every potential negative impact and create solutions to lessen the harm. The NYSDOT claims this project – which is expected to take between two to three years and cost at least $1 billion to build – is not a major project that would require an EIS.

Considering the many harms that the Kensington inflicted on the Black neighborhood closest to it and the magnitude of this project, we urge the NYSDOT to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). This is the standard environmental analysis for any major infrastructure project. The agency must take a hard look at the impacts of its redevelopment plan.

Conducting an EIS for the Kensington project isn’t just good policy. It’s the law. For a redevelopment project like this, which impacts a lower income Black neighborhood that has delt with decades of pollution, an EIS is required under federal and state laws.

Many residents who live near the Kensington feel their voices won’t get listened to and that the NYSDOT is already dead set on executing its plan. After a recent community meeting with the NYSDOT, one person told WKBW, “The deal is already done. This is a ‘dog and pony’ show.”

The NYCLU knows how important both listening to impacted communities and doing an Environmental Impact Statement are when it comes to infrastructure projects in working class Black communities.

In 2020, the NYCLU published a report calling for various changes to the state’s plan for replacing the I-81 viaduct in Syracuse. We warned that NYSDOT’s proposal put Black Syracuse residents’ health and economic security in danger. We drew our critique from both feedback we received from residents who lived closest to the viaduct and from the state’s draft Environmental Impact Statement.

The EIS allowed the NYCLU and the broader public to better understand the risks posed by the proposal. Eventually, we were able to get the NYSDOT to significantly strengthen its I-81 construction project, but this may not have happened without the initial Environmental Impact Statement. This level of deep analysis is critical for major construction projects like I-81 and the Kensington Expressway.

The NYSDOT must conduct an Environmental Impact Statement to fully assess the impacts of the Kensington project. Black residents that live adjacent to the project and who will again shoulder the impacts for generations to come, must have their voices heard. The NYSDOT should also ensure that harm reduction is central to this project, and that residents share in any benefits from it.

We cannot let the history of the Kensington Expressway repeat itself.