A shocking percentage of jaywalking stops in Washington state are aimed at unhoused people, a new report finds — but other states don't even collect basic data on how these laws impact vulnerable communities, nevermind take action to reform them.

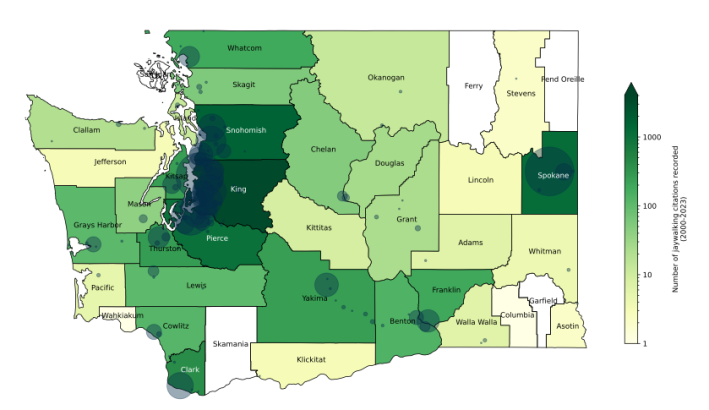

In what may be the first statewide analysis of the housing status of pedestrians stopped for crossing against a signal, walking on the roadway, or otherwise using their streets in an unsanctioned way, researchers at Transportation Choices Coalition found that unhoused folks were involved in 41 percent of all stops between 2000 and 2023. And because just 0.4 percent of residents of the Evergreen state are unhoused, that means they're being overrepresented by a factor of more than 100.

Even that shocking stat may be an underestimate, the report authors say, because "someone living unhoused could conceivably provide an officer with the home address of a family member or friend ... while it is less probable that someone who is stably housed would provide a homeless shelter, service provider, or transitional supportive housing location as their home address."

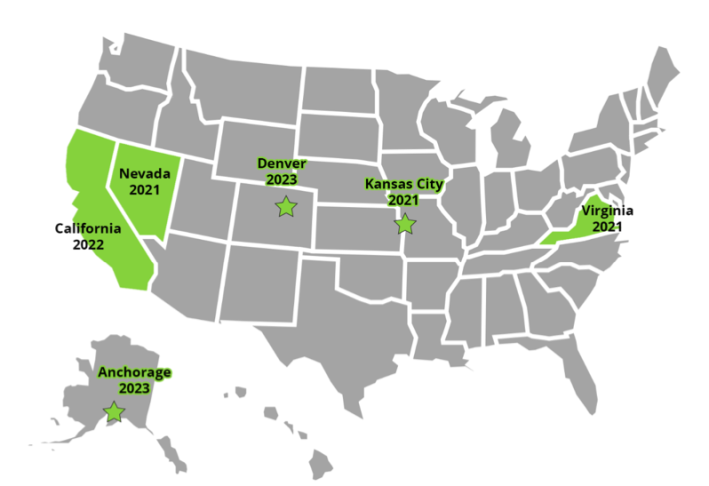

That disturbing finding is similar to comparable research in communities like Denver and Salt Lake City, the latter of which was once found to be conducting two-thirds of its jaywalking stops within a block of single homeless shelter. And report author Ethan Campbell suspects the problem is even more widespread across the country — even if most communities aren't even bothering to track the housing status of jaywalkers, never mind crafting policy reforms to decriminalize them.

"It’s not surprising, and it shouldn’t be," added Campbell. "Folks who are homeless are disproportionately present in every sort of statistic showing harm, whether it’s traffic fatalities, deaths from collisions, you name it. It all boils down to vulnerability."

Also much like other U.S. communities, Washington's jaywalking stops don't appear to have any meaningful impact on making streets safer — even as they can have devastating impacts on those who experience them.

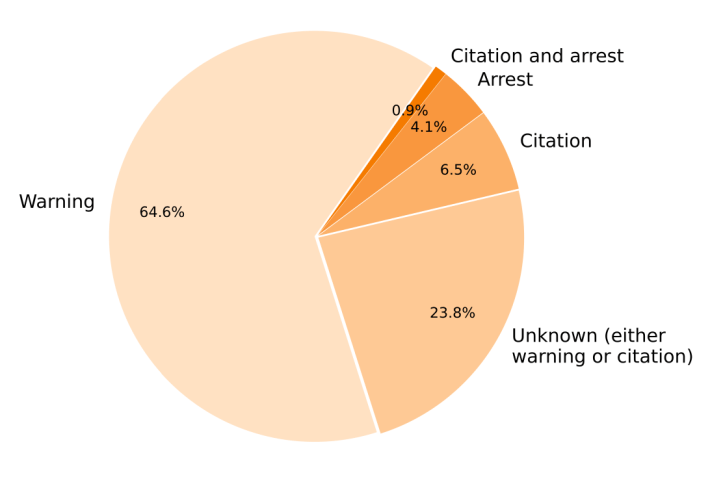

While few of the stops that the Washington researchers analyzed led to tickets and only 5 percent led to outright arrests those penalties were often borne by those who could least afford them, like the unhoused and very low-income. And while it was also rare for jaywalking stops to escalate to use of police force or a full-on pursuit — only 3 percent of the cases the researchers analyzed ended in either — Black pedestrians were far more likely to fall victim to both, receiving detentions 4.7 times and receiving tickets 2.7 times more frequently than their share of the population.

Campbell was particularly disturbed by the stories buried within these stats. During his research, he pored over hundreds of dispatch logs which detailed pedestrians being "tackled and punched and tased and choked and held at gunpoint" at the hands of police; in one particularly haunting story, a young Black man briefly lost consciousness after a police officer placed him in a neck restraint for resisting a citation, in a disturbing echo of the murders of George Floyd, Eric Garner, and so many more.

"It wouldn’t make the media; this man will never see a misconduct settlement," Campbell added. "What the officer was doing was probably perfectly legal. But that interaction should never have happened in the first place."

Even if that level of violence is rare, Campbell says other forms of police escalation are not. A staggering 77 percent of the stops he reviewed led to warrant checks for unrelated charges, even if the so-called perp wasn't doing anything more suspicious than crossing a road that wasn't designed with pedestrians in mind.

The majority of jaywalking stops in the analysis occurred more than 452 feet from the nearest marked crosswalk or signalized intersection, about the length of 1.5 football fields — along exactly the kind of dangerous arterials to which unhoused people are shunted by anti-loitering laws that bar them from merely existing in more walkable neighborhoods.

"These aren’t police stops to teach people how to cross the street; they’re pretextual in nature," explains Hester Serebrin, policy director at Transportation Choices Coalition, which commissioned the report. "They're essentially a fishing expedition. ... The financial impacts of tickets are real, and the mobility impacts of resolving a ticket are real. But the stops themselves are just as harmful, if not more harmful, because that’s where people get hurt, get pursued, or feel afraid."

All that problematic policing, meanwhile, isn't even leading to safety gains. When Washington became the first state in America to declare its intention to achieve Vision Zero in 2000 it recorded 66 pedestrian deaths; by 2023, deaths had shot up to 138 instead.

Serebrin hopes her group's data will be enough to convince Washington lawmakers to pass the Free to Walk bill, which would decriminalize jaywalking unless pedestrians were "creating an immediately risk for themselves or others" and add the Evergreen State to the growing ranks of U.S. communities to embrace similar reforms. And once that's done, she's hopeful it will open up a broader conversation about what would make walkers safer — in every sense of the word.

"If we want to meet our climate goals, we need people to feel safe — not just from a crash perspective, but from the perspective of interpersonal safety and harassment," she added. "This bill is not a substitute for better street design, slower speeds, and other policies that keep people safe. But we also don’t have data that jaywalking laws keep people safe, either."