A freeway-to-boulevard project that’s been held up as the poster child for the Biden administration’s transportation equity goals is sparking controversy among residents who worry it’s simply a “highway by another name” — and raising tough questions about what it really means to "reconnect" a community.

On Nov. 4, Detroit residents will gather for a community conversation about the region’s long-fought “I-375 project,” which would dismantle a mile-long, below-grade freeway that runs like a moat beneath just a handful of bridges in downtown Motor City, and replace it with an at-grade boulevard and nearly 30 acres of developable land. That move, proponents say, is a crucial first step towards making the city more pedestrian and bike-friendly, and potentially reparating the predominantly Black descendants of Paradise Valley and Black Bottom, whose homes and businesses were razed from the land in the name of “slum clearance” before the highway was installed.

The project has won praise from Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who awarded it a $100-million federal Reconnecting Communities grant and lauded the Michigan Department of Transportation’s commitment to “rich and thorough community input” at a 2022 White House event. He also held up the agency as a model of how other transportation departments can “avoid layers of review that might otherwise have been necessary.”

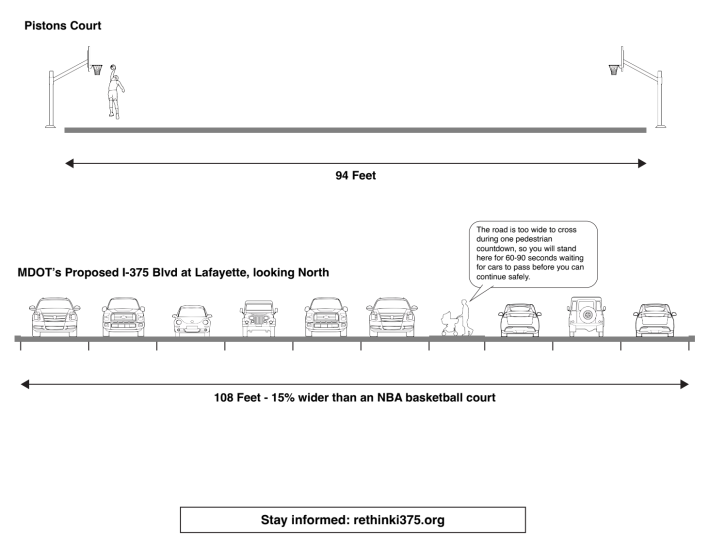

According to the project’s critics, though, that efficient-yet-meticulous review process has resulted in a dangerous road that at some points is wider than an NBA stadium is long, which neither meaningfully “reconnects” any communities at all, nor adequately centers the descendants of the neighborhoods that once stood in the freeway’s footprint. And that debate echoes an ongoing national conversation among advocates about what it will take for Buttigieg's signature equity program to deliver on its promises — rather than providing equity-washed political cover for projects that feel less like radical rethinks than disappointing compromises.

“I just feel like, wow; community engagement is broken,” said Bryan Boyer, a resident of the neighborhood around the new boulevard and an assistant professor of practice in at the University of Michigan’s department of architecture. “MDOT has been checking the boxes; on paper, they did a good job. But it’s resulting in a plan that I don’t think anybody is happy with. The suburban commuters are going to have a slower trip downtown; my neighbors and I are going to have more pedestrian danger; the businesses will have years of closures. There’s no winner.”

‘The world stopped in 2020 and MDOT didn’t'

Back in 2017 when he first joined the local advisory committee, Boyer says the community engagement around the I-375 project often was as “rich and thorough” as Buttigieg describes.

When that engagement took a predictable nosedive during the COVID-19 quarantine, though, he says transportation officials pressed on, ignoring the advice of groups like the Untokening who warned that “equitable participation is impossible” while America was still reeling from the effects of a largely uncontained pandemic.

“The world stopped in 2020, and MDOT didn’t,” added Boyer. “That doesn’t mean it’s some big, evil conspiracy, but it also doesn’t mean the traffic engineers had everybody on board.”

In January 2021 — months before the vaccine was widely available to most Michigan residents — a virtual Environmental Assessment hearing held by MDOT attracted just 169 people; an in-person meeting held a month later attracted only 22. According to the FHWA, though, that was enough to certify a “finding of no significant impact” for the project, which empowered engineers to begin preliminary designs.

In the months since, Boyer says many of his neighbors have begun to re-engage with the project, only to find that what had once been described to them as an effort to comprehensively reimagine a highway transformed into something all too familiar: yet another a six-lane stroad that, at one point, swells to a shocking nine lanes across.

Until he really dug around in the renderings, though, even Boyer — who heads U of M’s Bachelor of Science in Urban Technology — couldn’t tell that the road’s maximum width was 15 percent wider than the Pistons’ NBA court is long. An anonymous community site dedicated to sharing details about the opposition to the project, Rethink I-375, refers to it as "highway by another name."

At recent community engagement sessions, meanwhile, Boyer says the number of lanes wasn’t even a topic that was for up discussion.

“You can really see the shift in quality and priorities,” he added. “Now, it’s like, ‘This is the mock-up for the road; now we’re going to ask you questions about which tree grates you prefer.’ Or, ‘Which artists that have some connection to Paradise Valley and Black Bottom should we hire to paint a mural, and whose face should be on it?’ But they’re not asking: is this a safe place? Will pedestrians ever come here? Will they notice the historical marker, or will they be breezing by it in a car at 50 miles per hour?”

‘A thriving Black community’ destroyed

As co-chair of city’s council’s Reparations Task Force and a Detroit planning commissioner, Lauren Hood has been pushing for more discussion about how the new developable land created by the freeways’ removal might be leveraged for the benefit of the descendants of BIPOC Detroiters who were most affected by its harms.

The nonprofit Detroit Future City calculated than more than 43,000 people — 70 percent of whom were Black — were displaced as a result of the city’s urban renewal policies. And while those policies predated I-375 and extended beyond its boundaries, they were certainly accelerated once federal highway money was put on the table.

“There’s lots of activists who are like, ‘You’ll never bring it back, don’t even try,’” she said. “But lots of us say, ‘What about a land trust? What about a cultural corridor? What about a business corridor for descendants of the displaced?’”

Hood stressed that when the residents of Paradise Valley and Black Bottom lost their neighborhoods, they also lost their neighbors — and with them, a collective political power that might have given them a stronger voice in Detroit’s future. And that profound loss was suffered by Black communities across the country.

“I think what’s most important to understand [about the destruction of these neighborhoods] is that it was intentional,” Hood added. “There was intent at the federal level to diminish the capacity of these thriving Black communities. A lot of these Reconnecting Communities projects have the same story; there was a thriving Black community, there was a period of urban renewal where it was decided that there needed to be a highway, and this is where it needed to go.”

'The most progressive yet realistic option we can get'

For all these criticisms, though, some Detroiters see the I-375 project as a net good — even if there’s far more work to be done to make it safer for pedestrians and a better vehicle for intergenerational healing.

Because at the end of the day, it just as easily could have been replaced with yet another highway.

“They’re making it look like they woke up one day and decided they were going to remedy all these social equity issues, but that’s not what caused this project to come about,” said Todd Scott, executive director of the Detroit Greenways Coalition. “It came about because the bridges [across 375] are at the end of their lives, and something has to be done about that … [MDOT has] sort of taken a Reconnecting Communities paintbrush to the project, but that’s just how you play the game. It’s not going to be up to them to do the restorative justice. It’s up to the city of Detroit.”

Rather than urging MDOT to drastically narrow the proposed boulevard — whose overall width, its designers say, is pretty much locked in — Scott’s group is advocating for what he sees as more modest but impactful design changes, like removing turn lanes, designing for tighter turn radii at intersections, and bike signal heads along a proposed cycle track. He also hopes excess lanes can eventually be repurposed, though he believes not building them at all isn’t a realistic option.

“Our goal is to advocate for the most progressive yet realistic option that we can get,” Scott added. “MDOT might reduce the number of lanes, but it’s not likely. If you added two minutes of delay during peak travel, you’re going to lose the support of all the major employers in the downtown area, then the mayor, and then you’re done; the project doesn’t happen.”

Hood is also focused on the future. She’s hoping to identify a coalition of advocates to lead the restorative justice aspects of the project as it gets further underway, even if justice wasn’t the initial impetus for the highway being torn down.

“I don’t want to hold the traffic planners accountable because they can’t get their heads around a reparative frame,” Hood said. “Because of course they can’t … We can’t expect MDOT to be doing this reparative justice work; it’s not what they do. We need the community to lead that.”

‘A big road in place of a highway’

Boyer, for his part, is still hopeful that the community can have a bigger voice in reimagining the I-375 project before it breaks ground. He’s particularly looking forward to the results of an updated traffic study promised by MDOT, which may help make the case that the Motor City doesn’t need a mega-road in a post-pandemic world with far fewer downtown commuters. He’s also excited for this weekend’s community town hall, which he says will offer neighbors a rare opportunity to speak out about their hopes for the corridor, rather than an “atomized science fair” of display stations that don’t really allow residents to hear from one another.

If nothing else, though, Detroit’s tumultuous experience may serve as a reminder that for “reconnecting communities” to be more than a slogan, we need to ask ourselves tough questions about which “communities” we’re serving — and which professions are best positioned to perform that reunification.

“The way to approach this kind of project isn’t just, ‘let’s do a better version of the road,’” Boyer added. “We need to ask more fundamental questions about the future of the place … If you knew what it’s going to be from the beginning — a big road in place of a highway — you might as well have not done any community engagement at all.”

A representative from the City of Detroit declined to comment on this story.

After this story was published, the Michigan Department of Transportation sent the following statement to Streetsblog:

"In 2017, MDOT initiated an Environmental Assessment (EA) to pick up where a previous Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) study left off. The PEL study started in 2014 and was led by the Detroit Downtown Development Authority in association with the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy and MDOT and concluded in 2016 with six illustrative alternatives for the project.The EA picked up where the PEL left off to further identify and document the human and natural impacts associated with any proposed improvements.

Guided by the study’s purpose and need and extensive stakeholder engagement, a preferred alternative was developed. Up to the public hearing, seven advisory committee meetings, 71 individual meetings with 25 different stakeholder groups (residential and business) and 12 workshops with the city were conducted.

Third party outreach included surveys conducted by Curbed Detroit publication and Michigan State Representative Stephanie Chang."