Agencies and policymakers can come together to pull U.S. transit out of its fiscal "death spiral" by focusing on low-cost moves to create a "virtuous cycle" of increased service, ridership and revenues, a new report argues.

Across the country, post-pandemic budget woes are forcing transit agencies to tighten their belts, raising the possibility of devastating service cuts against the backdrop of a worsening climate crisis. Faced with a $26 million shortfall, Milwaukee County announced in June that it might have to cut more than half of all bus routes by 2025; New York’s MTA floated a 2023 budget projecting a $600 million deficit; WMATA’s $750 million in red ink, meanwhile, could put the DC-area transit agency near collapse. And there are plenty more examples where that came from.

According to a new report from the Urban Institute, though, transit can emerge from the pandemic even stronger by restructuring funding sources to increase service — and potentially, pave the way toward long-term fiscal stability.

“Diversity of funding sources is crucial for this stability,” said Lindiwe Rennert, co-author of the report. “Therefore, we shouldn't get hyper-focused on finding the sole best source of funding. If there is an option, take it. More is more. And similarly, more funding equals more and better service, [which] equals more and better ridership."

To arrive at that recommendation, Rennert and her co-author Yonah Freemark compared funding structures in five metropolitan areas — Washington, San Antonio, Denver, San Francisco, and Cincinnati — to identify historical causes of fiscal instability in transit, analyze responses to the current budget crisis, and prescribe new funding models that would stabilize budgets and lead to better service in the future.

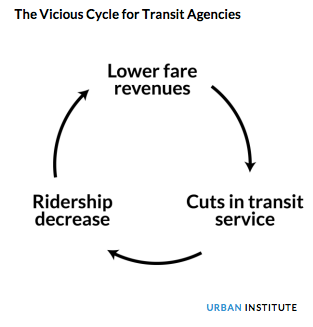

Absent a federal lifeline that doesn't seem poised to come anytime soon, the researchers say transit agencies are often stuck in a “vicious cycle” in which decreased ridership leads to lower fare revenues and service cuts, which leads to even lower ridership, and so on.

This is especially damning for agencies like California's Bay Area Rapid Transit, whose funding model relies heavily on fare revenue. Freemark points out, though, that just a few years ago, BART's approach was lauded as a national success— before ridership took a nosedive.

“[BART was] able to raise a huge amount of money from fares, and were able to do so in a way that largely required less public subsidy,” Freemark, who also directs UI’s Land Use Lab, said. “And so I think the lesson from BART is actually not that BART is necessarily doing something specifically wrong, but rather that we just need a diversity of funding sources. Because you never really know what kind of crisis will affect your specific transit agency's funding source.”

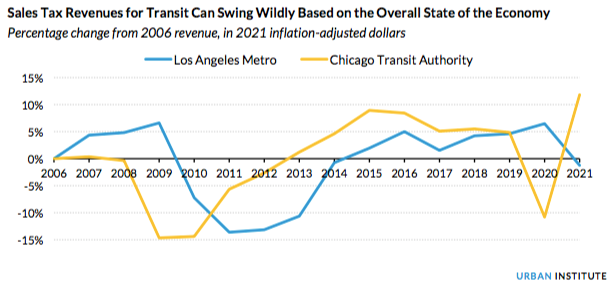

And even if they don't depend exclusively on fares to pay the bills, Freemark and his colleagues say too many agencies over-rely on another limited revenue source, like sales taxes which fluctuate with the overall strength of the economy.

So how do you turn that vicious cycle into a virtuous one?

First, Freemark and Rennert call on local and state governments to tap into existing transportation funding traditionally geared toward highways, which can often legally be "flexed" to transit projects. They should also swap dependence on sales taxes for “less regressive” taxes on property, high-income individuals, and driving, however politically difficult those battles might be to wage.

The report says transit agencies themselves can make changes, too, by using those new funding sources to increase service wherever possible and bolster public support for transit — and, in the long run, boost ridership. To offset those costs, the report also recommends optimizing efficiency by enforcing interventions like bus lanes, rather than relying on layoffs or service cuts to stay lean.

“If I were to double the speed of a bus route and run the same number of buses, not only would I be increasing the quality of service for the customers on this line, but I would actually be reducing the number of buses I need to actually use the line by 50 percent," explains Freemark. "That is an incredible potential operation saving, but it requires transit systems to work with local governments to install those bus lanes and to make buses significantly faster in their communities.”

And once that "virtuous cycle" is up and running, the analysts urge transit agencies to create rainy day funds similar to the ones many state and local governments use to respond to year-to-year fluctuations in tax revenue, and play the long game to help weather unforeseen shocks.

By focusing on increasing ridership rather than just cutting expenses, Freemark and Rennert argue that agencies can help build the political will to direct more funds toward transit, creating yet another positive feedback loop. That model, though, relies on robust public engagement to get the ball rolling in the first place.

“I think if we can get [the virtuous cycle] into conversation just as much as the 'doomsday spiral' ... that's been mentioned everywhere, then we start to change [the transit-as-money-pit] narrative,” Rennert said. “Without the language or the tools to change that conversation, we struggle.”