Tennessee's decade-long surge in pedestrian deaths has less to do with the size of the cars that strike walkers than the speed of roads on which they were struck, according to a new study that could have big implications for policymakers in other car-dependent states.

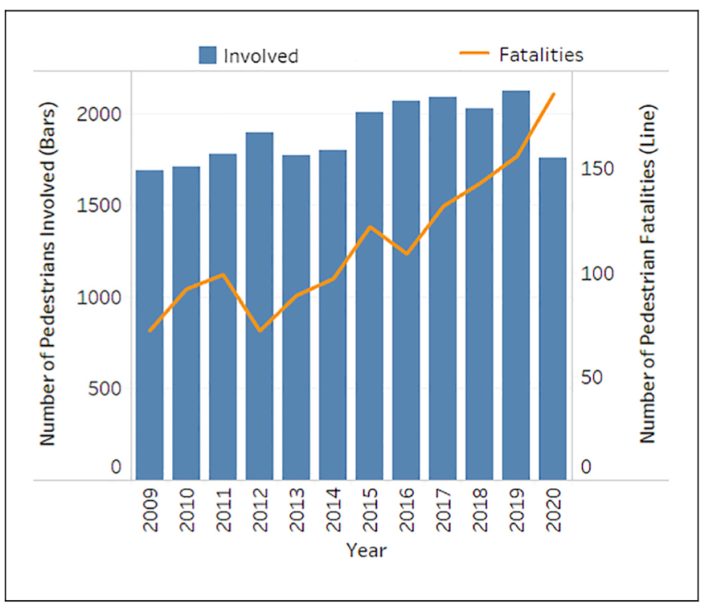

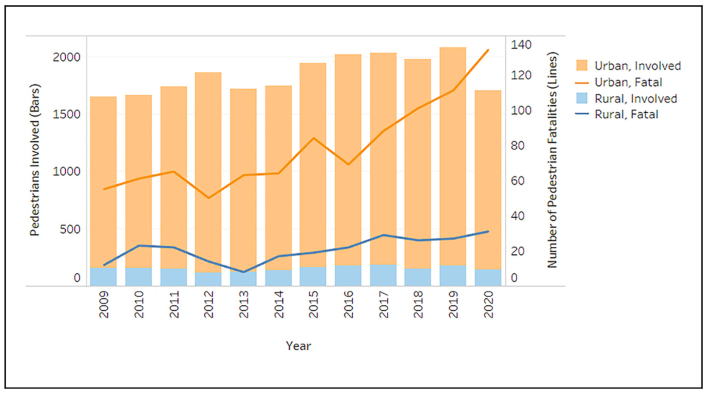

In a new paper published in Transportation Research Record, analysts found that the Volunteer State's 117-percent increase in pedestrian deaths between 2009 and 2019 was tightly correlated with an increasing number of crashes on straight, multi-lane roads with speed limits over 35 miles per hour in urban and suburban areas — or, as they're better known among Vision Zero advocates, arterial "stroads" that combine the features of neighborhood streets with a car-oriented roads to deadly effect.

Study author Christopher Cherry pointed out, though, that "Tennessee didn’t go on an arterial-building binge" over the last decade — and that other common hypotheses don't explain the death toll, either. The researchers found, for instance, that older pedestrians did not experience an increase in walking deaths, challenging the assumption that pedestrian fatalities were simply increasing in tandem with the average American lifespan, since older people are less likely to survive car crashes overall.

And contrary to another wildly popular hypothesis, the researchers also found that, at least in Tennessee, the increasing prevalence of big SUVs and pick-up trucks wasn't the factor driving the death surge — though that doesn't mean they don't need regulation, particularly in places where stroads have been tamed.

"To be clear, [large cars] are more dangerous to pedestrians. I don’t want to absolve big trucks from the story," stressed Cherry. "But the more important thing that we should be focusing on — and it's something that urban transportation professionals have a lot more control over — is speed on urban arterials. If you’re hit by a car, a truck or a bus going at 50 mph, the outcome is going to be the same for pedestrians: you're probably not going to make it."

So if megacar drivers and asphalt-addicted DOT leaders on stroad-building benders aren't to blame for Tennesee's death surge: what is?

Cherry isn't sure, but he hypothesizes that the phenomenon known as the suburbanization of poverty may play a role. Tennessee communities have been "auto-oriented, arterial-oriented, and stroad-oriented" for generations — characteristics he says they share with "probably 90 percent" of U.S. cities — but Cherry suspects that a rising number of residents simply have no choice but to walk on the state's most-dangerous roads, particularly as incomes fall and poor residents who can't afford cars are pushed out of walkable downtowns and towards the sprawling fringe.

That hypothesis was partially confirmed by his study, which found that severe crashes increasingly tend to happen on arterials located further from pedestrians' homes.

"What that results in is a place that didn’t have that intensity of pedestrian activity before suddenly has a lot of it," he added. "This is a hypothesis, but I think it has to do with folks who are captive to transit and walking, without any of the infrastructure to support that."

Whether or not his hypothesis proves true, Cherry's research makes it clear that state and local transportation leaders must redesign their stroads for safety now, rather than continuously deflecting blame for their rising death tolls onto individual road users — or even onto NHTSA for its failure to regulate large vehicles.

"This is not to say that we should give up on making sure these vehicles are safer for vulnerable road users," Cherry said. "But I’m a little concerned that there’s a misplaced emphasis on solving [the vehicle design] problem, rather than solving the problem with road design. ... We need to design roads where it’s almost impossible to kill someone. That culture change is happening at DOTs, but it’s not happening fast enough."