This article was originally published in the Vision Zero Cities Journal, as part of Transportation Alternatives’ 2025 Vision Zero Cities conference, which will take place Oct. 28-30 in New York City.

In most American cities, even the best public transit administrators face untenable choices, ranging from deferred maintenance to service cuts. With few exceptions, underfunded and underperforming transit is a feature, not a bug, of American life. It doesn’t have to be this way. Quality public transit, with steady subsidy and supportive land use, can thrive in an auto-centric society as it has in cities like New York, Boston, and San Francisco.

The United States once had virtually no truly public-owned transit. However, riders in the late 19th and early 20th centuries enjoyed access to the world’s largest privately developed and operated transit systems. How was this possible?

Private transit companies initially attracted capital because streetcars and elevated lines enabled the profitable development of peripheral land. Developers built residential neighborhoods and transit lines connected them to the heart of the city, drawing new residents who would then pay fares to ride the transit line. Many neighborhoods that we consider urban today initially developed as “streetcar suburbs,” including brownstone Brooklyn, San Francisco’s Sunset District, and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Although land development generated initial revenue, fare boxes were soon expected to sustain the transit service. Transit companies that survived the land development phase only remained profitable through monopolistic consolidation, fare increases, labor exploitation, and maximizing the use of aging equipment. Taking transit wasn’t pleasant — one result was reformer outrage and the establishment of public service commissions that attempted to regulate private companies’ fares, routes, and service levels — but it was fast, frequent, affordable, and well-connected.

Transit riders and politicians, seeing only defects, failed to grasp how much transit service they enjoyed without public investment. In 1900, American transit riders from Atlanta to Los Angeles had far more access to streetcar transit than their European counterparts. The private companies, despite their many flaws, delivered a valuable public utility with minimal public subsidy and regulation.

The transit companies’ monopoly was broken when the mass automobile arrived in the 1920s and '30s. Affluent riders bought cars and fled to new auto-centric suburbs; some were tired of the old streetcars, while others simply preferred the privacy and speed of automobiles. City leaders invested in pavement for new and widened streets and highways, which only led to even more cars being pumped onto city streets.

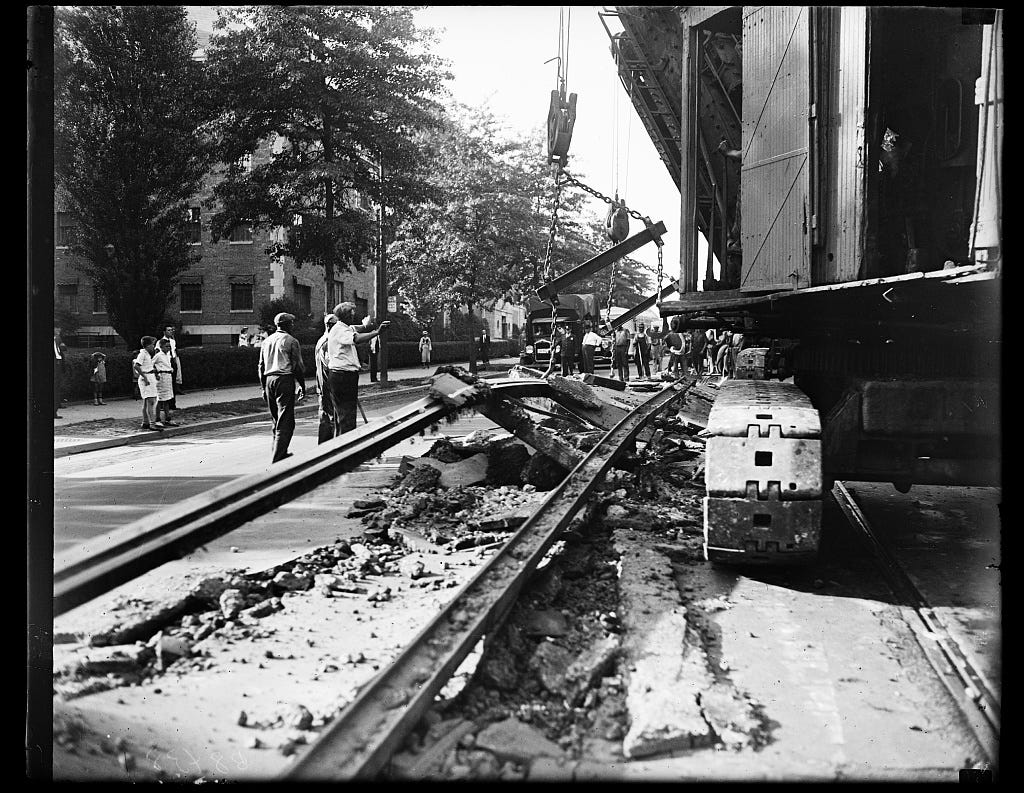

Starting in the 1920s and '30s, private transit companies experienced significant declines in ridership and growing difficulty operating streetcars and new buses on congested city streets. Limited by public commissioners on fare increases, the owners slashed service frequency, abandoned express downtown service plans, terminated unprofitable lines, failed to expand into growing suburbs, and replaced streetcar systems with cheaper and less frequent buses. Nothing much helped: the transit companies collapsed in full public view, but few city or state leaders seemed to care. After all, private transit companies were widely viewed as monopolistic bad actors despite the necessary service they had provided. Streetcars were also unfairly blamed for slowing down automobile traffic.

Vulture capitalists, such as National City Lines, stepped into the void. These entrepreneurs aimed to help automotive industry patrons sell buses instead of streetcars, and are notorious for degrading transit in the 1940s and 1950s. While National City, which controlled a fraction of total transit ownership nationally, is usually blamed for all streetcar losses, almost all private transit operators took the same slash-and-burn approach to legacy streetcars. In most cities, the government encouraged swapping buses for streetcars to speed up traffic, or intervened only when much of the expensive transit infrastructure, such as streetcar tracks, had been dismantled, and only a few bus lines remained.

Fearing the loss of all transit service, on which many riders still depended, the government grudgingly entered the transit business after World War II. Sadly, public ownership was no panacea. Public transit agencies fell into three broad categories: “pay as you go” systems, where fare revenue was expected to cover the entire cost of operations; poorly subsidized transit systems; and deeply subsidized systems.

The “pay as you go” model, which relied solely on fares for funding and most directly emulated the fully private transit system it replaced, had a very short lifespan in the United States. Though it met a similar fate in Detroit, Cleveland, and Seattle, this flawed management model is best exemplified by the struggling Chicago Transit Authority, created in 1945.

While the CTA initially benefited from tax exemption, it had no public funding to help it through farebox gaps. Steep ridership losses after World War II could only be addressed through reductions in service; these actions resulted in lost fare revenue and growing customer dissatisfaction. By the late 1950s, the CTA had ripped out the nation’s most impressive streetcar network to make way for buses. The managers cut service and deferred maintenance for decades. The state grudgingly stepped in to bail out the CTA in 1971 as complete collapse loomed. However, the limited regional taxes the state created did not right the ship, so the CTA became a poorly subsidized entity, requiring decades of additional cuts.

The “poorly subsidized” transit agency model dominated in the 1960s and '70s, when the public sector across the nation finally absorbed the remnants of private operators. Politicians, more responsive to automobile owners than transit riders — a growing proportion of whom were Black and low-income — provided limited funding from local, regional, or state sources. Fares had to rise to pay the bills, and annual cuts made riding transit an expensive, inconvenient, and undesirable second choice. Federal subsidies beginning in the 1960s, primarily for capital funding, couldn’t make up the losses. Transit managers had no control over land use around their stations. So, even when they built high-quality rail, usually with federal support, they were unable to profit from strong ridership growth.

Agencies with the most extreme pandemic-related ridership losses, such as those in Chicago and Philadelphia, have been vulnerable for decades due to their poorly subsidized and inadequate funding models. Their systems were outdated, and long-suffering riders, who had endured cuts and poor maintenance long before the pandemic, fled to cars. Agency leaders annually travel to state capitals to beg for bailouts, while automobile infrastructure subsidies expand without controversy. As a result, transit is a marginal part of American life, while it has grown or stabilized in other parts of North America, Europe, and globally.

The few domestic exceptions to this sad story are the deeply subsidized agencies in cities like New York, Boston, and San Francisco, where the government entered the transit business in the early twentieth century, when urbanites still rode public transit en masse. By taking over systems before they reached total collapse, the new agencies were able to maintain higher ridership and avoid having to start from scratch. Public managers developed express rail systems, such as the IND rail lines in New York or the Sunset Tunnel in San Francisco, that rivalled automobiles in speed. Managers in cities like these also benefited from dense urban cores that managed to avoid many of the parking requirements and highway construction that hollowed out other American cities.

This high-ridership, high-service model creates a virtuous cycle that maintains public and political support for subsidies. Boston’s first regional transit taxes, for instance, began in 1918, and government subsidies over the subsequent century evolved to fund the bulk of transit operations. In San Francisco, the city government directly contributed a total of $11 million (approximately $130 million in 2025 dollars) in property tax revenue to Muni operations between 1946 and 1956. Subsidies in cities like these sustained good service through the worst years.

Transit agencies in Boston, New York, and San Francisco continue to benefit from a range of robust local and state subsidies that enable them to operate at levels far beyond what fares can provide. These include annual provisions for local and state general revenue operations, capital subsidies, attractive bond financing, real estate taxes, sales taxes, mortgage transfer taxes, payroll taxes, parking fees, and tolls from bridges and tunnels. Agencies with strong local funding have leveraged federal capital grants since the 1960s to modernize and expand.

The contrast between the few winning and many losing transit systems is sharp today. In the wake of the 2020 pandemic, well-funded systems like New York’s MTA have come back stronger thanks to service predictability, and even San Francisco’s Muni has made great strides despite having the worst-performing return-to-office rate in the nation. Riders are back in Boston despite embarrassing maintenance shortcomings. The “winners” in transit are legacy cities that can draw on deep subsidies, decades of goodwill, and transit-oriented development.

These conditions and politics aren’t easily reproducible, but they aren’t impossible to pursue elsewhere. West Coast cities, such as Los Angeles, Seattle, and Portland, which experienced massive ridership losses, private transit collapse, and decades of weak public transit, have more recently developed robust local and regional funding models to expand rail and bus service.

Zoning reform, the elimination of minimum parking rules, and new transit-oriented development projects may generate a new generation of riders — and therefore more substantial political support for transit — in other cities. Context matters, too: traffic congestion, environmental concerns, and the rising costs of automobiles may drive future growth. Successful Bus Rapid Transit in cities like Richmond, VA, and Indianapolis, IN, has raised hopes of a high-quality, low-cost option that serves riders where they live.

A better understanding of the tactics and strategies employed by these rebounding transit cities, as well as the successful, deeply subsidized legacy cities, may help advocates elsewhere refine their transit visions.