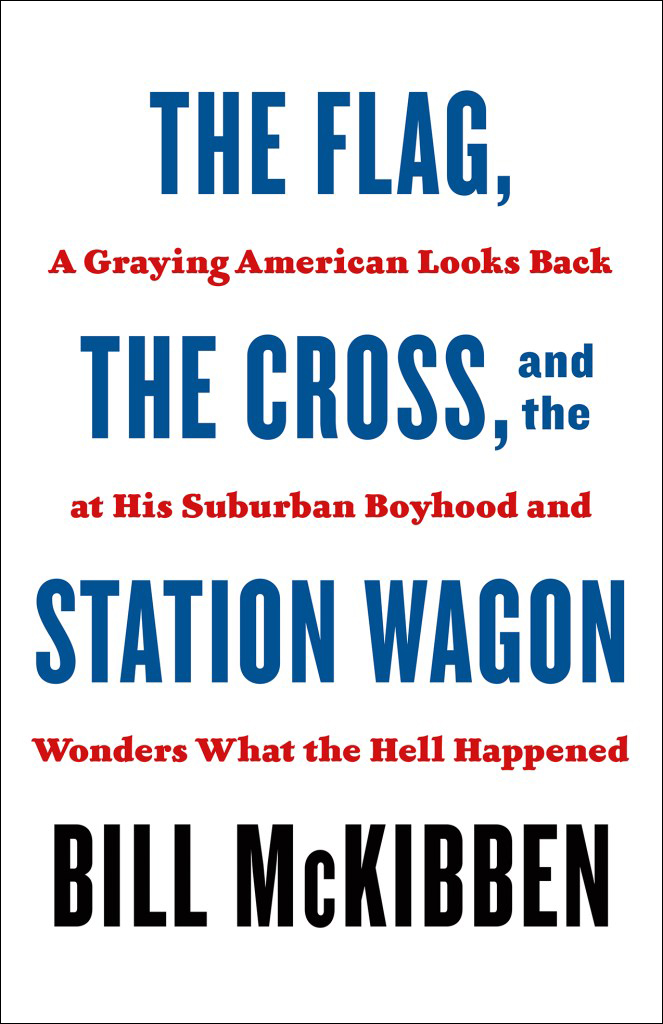

Since the publication of his seminal 1989 book, The End of Nature, activist and author Bill McKibben has become one of the most respected voices on climate and the environment in the world — and in the process, he's also quietly become one of the most prominent critics of America's car-dependent development pattern and its impact on our planet.

That's part of why he's supporting America Walks' first national Week Without Driving campaign (Oct. 2-8), which challenges U.S. residents to attempt to navigate their cities for seven days without an automobile, reflect on the barriers they face, and demand systemic changes that make active and shared transportation better for all of us.

As the challenge wraps up its final days, we sat down with McKibben to talk not just about what a week without driving means for our climate goals, but what it means for our humanity, and how to keep the momentum going long after the challenge is done.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length; a longer audio version will be made available later on our podcast, The Brake.

Kea Wilson: We're here today to talk about the Week Without Driving challenge and what not driving can do for the climate crisis. But before we get into that, I wanted to ask you a more general question, which stems from something you wrote in a recent review of two books that question the impact of automobiles in human and animal life. Tell me: why is it important that we try to, as you put it, "end the reign of the car"?

Bill McKibben: Well, the unfettered reign of the car has been a problem in so many ways. It's distorted everything from what our communities look like, to how we relate to each other to, of course, the carbon content of the atmosphere. And it remains the single biggest way that Americans heat up the planet.

Now, there's obviously lots of important and interesting stuff going on [in the transportation sector] right now. The rise of the EV, for instance, is a big, big improvement over an internal combustion car — if you need to drive a car, then that's what you should be driving. But just swapping one out for the other would be missing real opportunities.

My last book was a lot about the rise of the suburb and what that meant [for our country. Our biggest job since the end of World War II — the thing we spent the most of our money —on was the project of building bigger houses farther apart from each other. That was completely made possible by the rise of the automobile. ... And with that, everything shifted in our culture. So I don't think we can or should end cars. But I do think we should end planning all public policy with them as the most important thing in mind.

KW: Great. So let's get back to the Week Without Driving Campaign. I know that you've been supportive of America Walks in launching this campaign, the goal of which is, first, to get Americans that least try a week without driving, and second to get them to report back to their policymakers about what barriers they encounter when they do. Why are you on board with this effort? And what message do you hope it will send to policymakers all over the country?

BM: Well, I have it very easy in this regard, because I live deep in the woods, and I love to walk. The places I go and the things I most need to do all have to do with getting out of my head and away from screens, and walking is the perfect way to accomplish that. My watch tells me how many steps I take a day, and it tells me yesterday I took 25,000. The fall foliage is at its peak here, and I got to look at a lot of it.

But most Americans aren't so lucky. Most of our environments aren't really built very well for walking at all. It can be dangerous, not just because you might get run over, but because you have to breathe the endless exhaust of everything going by.

I've always been impressed with what happens when even a part of a city gets turned over to pedestrians; that changes everything. I did a long piece once for the New Yorker about a city in Brazil called Curitiba, [editors note: that article isn't available online, but you can read some of Bill's other reporting on Curitiba in Mother Jones, or in his book, "Hope, Human and Wild"]. Forty-five years ago now, it declared its downtown off limits to the automobile. And this was very, very progressive and unusual thing to do. ... The mayor had read Jane Jacobs, the great pioneering voice of benevolent urbanism, and decided that his city wouldn't be turned over to the car anymore.

He knew he'd face opposition. So he had the city's public works department and teachers and everybody else gather and over the course of one weekend, and they tore up the pavement from about a 20-block area and put down cobblestones. And when people came to work on Monday, at first there was outrage from the merchants; where would people park? But by the middle of the day, they'd seen such an increase in foot traffic and people down there enjoying themselves that the merchants from surrounding streets were demanding that their streets to be torn up so that people could walk to them.

I did that reporting 30 some years ago, but it's always stuck in my mind. Our unspoken assumption in this country that cars are the norm is a really stupid assumption. And if we didn't make that the norm — if we use the car for the things that it's good at, perhaps long distance travel in rural areas, or moving heavy objects about, or something like that — we'd be able to build cities, towns, suburbs that work for everybody, much, much better than they do now.

KW: As I hear you talking bout Curitiba, I just have to ask: why should we put our focus on building places like that — places where driving is optional — rather than just exclusively driving electric? Why do we need a Week Without Driving challenge rather than a Week Without Gasoline challenge? Do you think the environmentalist community is talking enough about mode shift and ending car dependency? Or is the conversation about electric cars sucking the air out of the room?

BM: We're not going to change everything that we've built in this country since the 1950s overnight. Having a car is not just a convenience, but a necessity for an awful lot of people. So given the incredible pressures that climate change presents — September was the most anomalously warm month we've ever measured on this planet, and we broke through the 1.5-degree Celsius barrier that we pledged to avoid in the Paris negotiations — the electric car is a good and useful thing.

But it's just as useful as the e-bike. It's just as useful as a pair of feet. And those things become more useful if you start prioritizing them. ... The thing to avoid I think, is continuing to make all our decisions about how we structure the physical spaces of our lives with the car in mind. Because that's what we've done for a very long time. I mean, suburban cul de sac developments are built around the turning radius of an automobile.

And it's not only hasn't proved ruinous for the environment. It's also proved, I think, pretty ruinous for our peace of mind. There's an interesting set of survey data where the pollsters have asked Americans, every year, whether or not they're happy with their lives. And the percentage of Americans who say they're very happy with their lives peaks sometime in the 1950s, and it goes downhill since — even though we're far richer than we were in the 1950s.

I think the reason, above all, is that we've reduced contact with other people. When you build bigger houses further apart from each other, mathematically, you run into each other a lot less. When you, instead, build communities that are denser, where people can enjoy walking to and from the things they need in the course of a day, you're going to bump into each other more often. And that's what we were built for.

The average American [today] has half as many close friends as the average American of the 1950s. That's a big loss for a socially evolved primate. And the 2,500-pound steel shell in which we encase ourselves for large periods of time has to have something to do with that increasingly hermit-like existence.

KW: I'm so glad you brought that up, because as I've been going over the responses on social media to the Week Without Driving campaign, a lot of it is not focused on that joy and connection you're talking about right now. It's focused on how not driving feels dangerous, or how many indignities people face on the road outside a car. How do we talk to policymakers about the joyfulness that's possible from choosing a life without driving, particularly if we facilitate a life without driving through great policy?

BM: I think one way to think about it is that it's a good idea to do a Week Without Driving, and it's an equally good idea to do a Week With a Lot of Walking. What does that end up being like? Because that, for me, is the pleasure of all this.

As I said before, I like to walk; I like seeing people; I like seeing the natural world. I just like the pendulum-like motion of my legs in action, carrying me hither and yon. And there's a long and well-developed literature on the pleasures of walking, going back, at least, to Henry David Thoreau's famous essay. I think of great writers of the present moment, like Rebecca Solnit, who have produced fantastic odes to the joys of walking. So I think I'd call in some writers and poets and artists and things — and maybe a doctor or two along the way. I mean, I'm not a doctor. But it strikes me as likely that it's pretty good for you to to be walking around instead of just sitting on a sofa, or depressing your ankle a quarter of an inch in order to accelerate your vehicle.

KW: What would you say to people who have completed the Week Without Driving, and want to keep the momentum going? What challenge would you put to them? Maybe a year without driving?

BM: Well, I would say a year with as much physical pleasure and physical engagement as possible! We have this remarkable thing that we've been given: a body. And in most cases, it really is pretty good at moving us about. It's only in the last 40 or 50 years that we've even begun to get away from that. We evolved to walk an awful lot of the time, if we're able to do it. And so I think that'd be my challenge: have as much fun out on two feet as you possibly can.