Big Buick is Watching.

America's car-dependent transportation system isn't just dooming us all to live lives that are more dangerous, expensive, and polluted — because it's also increasingly stripping us of our basic privacy rights whether or not we ever get behind the wheel, a new study finds.

In a fascinating new report from the Mozilla Foundation, a nonprofit watchdog group monitoring internet ethics, researchers did a deep-dive into the privacy policies of 25 international automakers to understand just what kind of data automotive interests are collecting on their drivers, passengers, and even people just walking down the street near a connected car. And they also dug into how automotive interests are using all that data, as well as how safely it's being protected against hackers, mass surveillance by governments, and others who might use it in harmful ways.

The results, to put it mildly, weren't good. Every single one of the 25 of the automakers in the study earned the group's damning "Privacy Not Included" warning label, "making cars the official worst category of products for privacy that [the organization had] ever reviewed" in its 20-year history.

"Car makers are bragging about how their cars are basically sophisticated computers that are smarter than your smart phones," said Zoë MacDonald, a co-author of the report. "But it doesn't seem like consumers are attaching very much scrutiny to it."

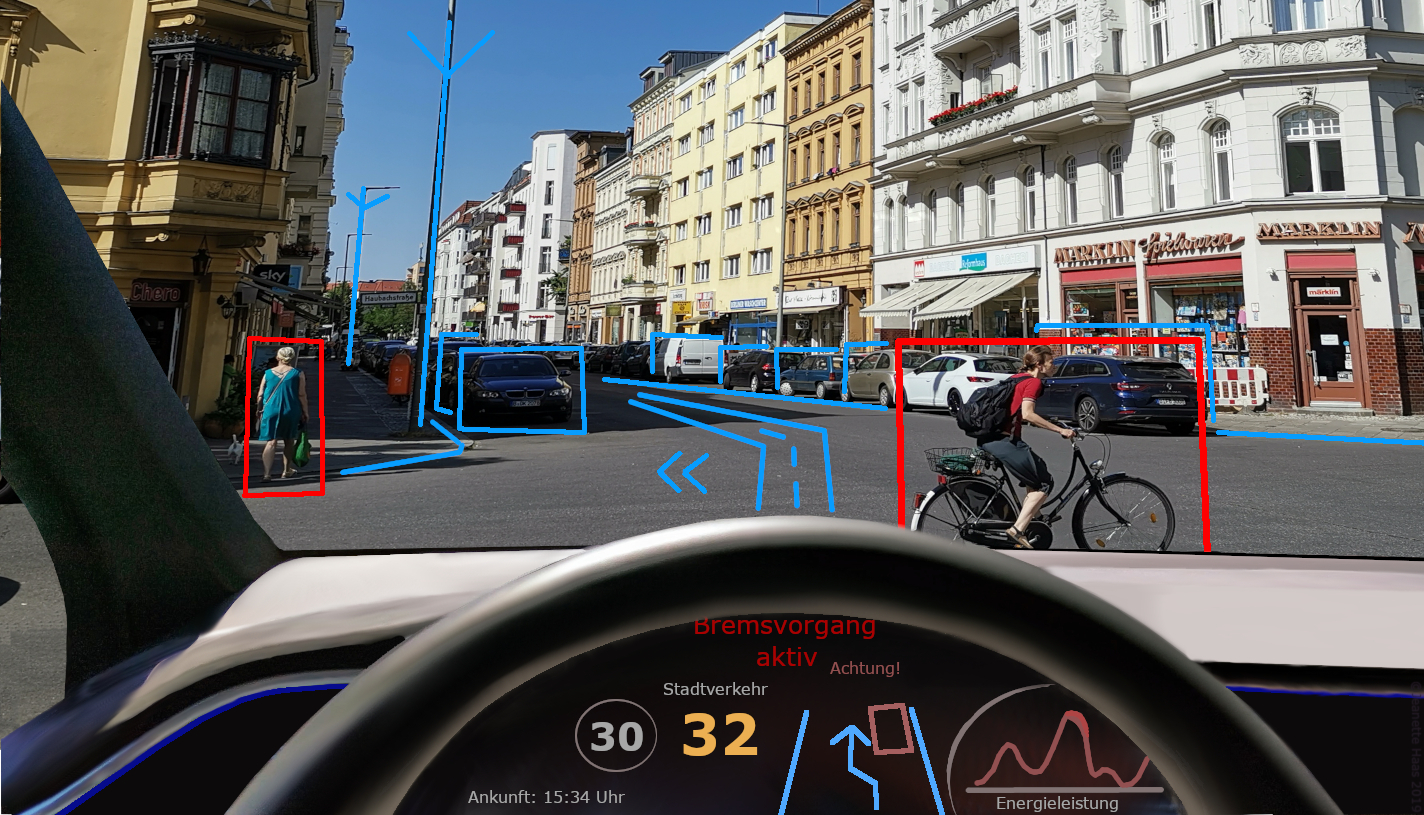

The transformation of the American car into a rolling data collection device, the researchers stress, isn't inherently dangerous, and it definitely isn't new. Since Volkswagen first put a computer onboard a vehicle way back in 1968, automakers have been using technology to monitor and manage some of the most essential functions of our cars, like fuel injection systems. Fast forward to today, and connected vehicle tech is ubiquitous — consultants at McKinsey have estimated that by 2030, 95 percent of new vehicles will be "smart" in some way — and pretty much all cars use at least some of that tech to collect essential safety information, like whether emergency services vehicles need to be dispatched if everyone involved in a crash has been rendered unable to call for help.

"It's hard to call data collection universally 'good' or 'bad,'" said MacDonald. "There are some pieces of data that strike me as wholly irrelevant — some of the cases with Nissan and Kia collecting our sexual history comes to mind — but other data, like monitoring the head and eye positions of the driver to detect fatigue, can be used to enhance safety or violate privacy. ... It comes down to the rules around how it can be used."

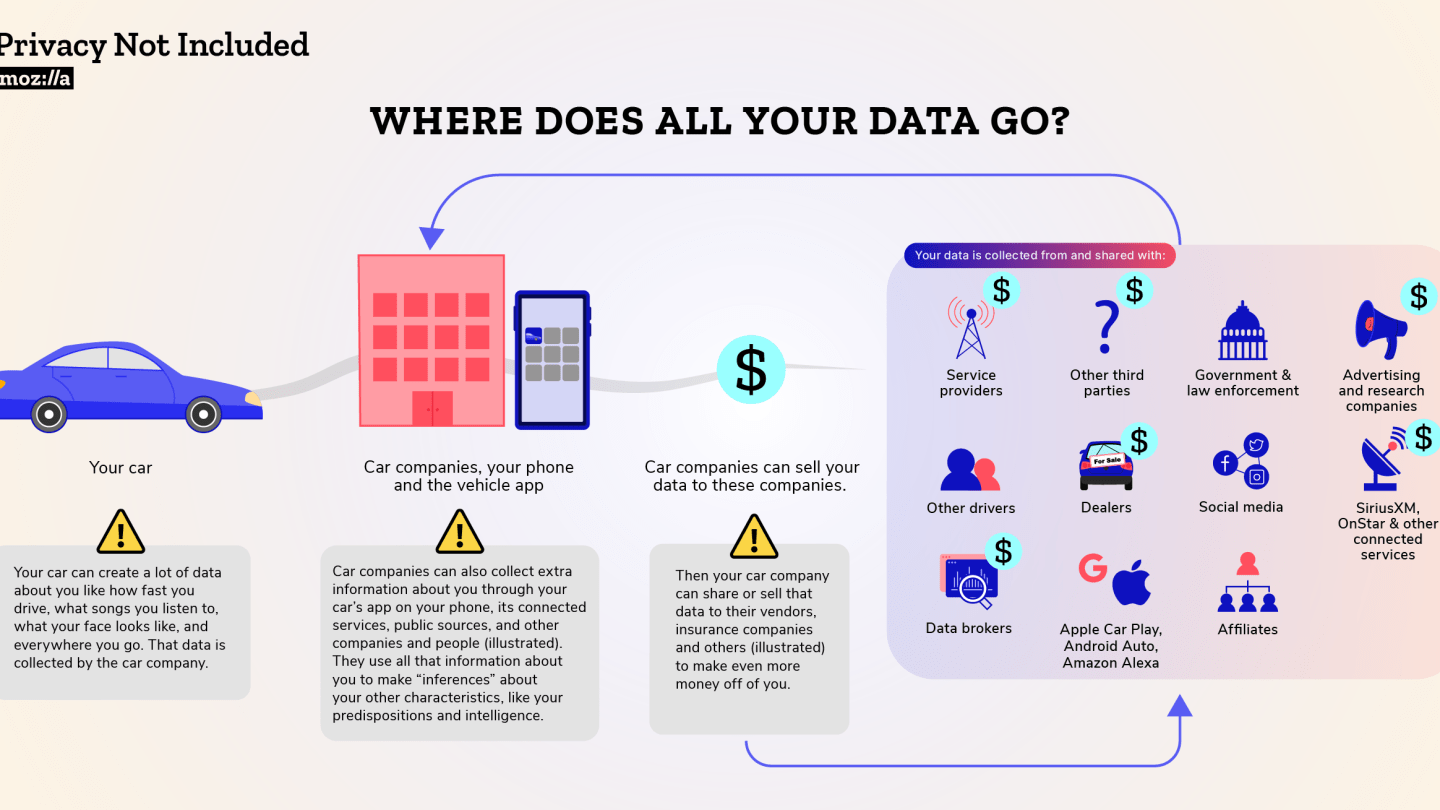

MacDonald explains that as cars and the universe of apps and services connected to them have evolved and become powerfully enmeshed with our other devices, the sheer range of personal information that auto companies have access to has exploded — and in car-dependent communities, virtually no one can opt out.

That's particularly true for drivers, about whom the most data is collected, but it's also true for vehicle passengers; 52 percent of vehicles in the study even collected data on the environments outside the car, like the movement of pedestrians. And even when that data is anonymized and aggregated, it can often be shockingly easy to extract the needle of an individual's details from the haystack of information.

"[Getting in a car is] sort of like you're hopping inside your smartphone," MacDonald adds. "In addition to input information — what you type, what you search for, the things you actively do on a screen — cars today have over 100 computers and dozens of mega-sophisticated sensors. They're collecting data when you're just sitting there, opening the door, putting on your seatbelt. These aren't activities you'd usually associate with a record being collected, but that's what's happening."

What cars know about their drivers — and everyone else

All in all, the Mozilla team outlined more than 150 data points that are frequently harvested by modern vehicles, including the most basic personal data, (e.g. our names, social security numbers, fingerprints, "faceprints," and "voiceprints,") financial information (e.g. credit card numbers and records of everything a vehicle occupant buys), and a disturbing array of health stats sourced from the phones plugged into infotainment systems and even the weight registered by the sensors in seats. When a driver shouts at her infotainment system to write an email to her boss, or her doctor, or her lawyer, the car often stores and analyzes the text of that email; when she calls 911 — or anyone else, for that matter — cars often remember exactly what she said.

And because modern cars also track exactly where, when, and with whom people travel, as well as those passengers' precise motions within the four walls of the car, they're also able to triangulate movement data against data from onboard cameras, sensors and phone connections to infer a terrifying range of other things about their users, like their aforementioned sexual history, immigration status, whether they belong to labor unions, and even their "philosophical beliefs."

Unsurprisingly, a whopping 76 percent of automakers say they've cashed in on that treasure trove of personal data by selling it to third parties like marketers. Worse, 84 percent said they've either sold or "shared" it for free, including with governments and law enforcement — and 56 percent say they only require officials to submit an informal "request" rather than a formal court order. That has particularly terrifying implications in an era when many U.S. communities are contemplating Draconian laws against crimes like so-called "abortion trafficking" between states, while simultaneously stripping them of any mobility options besides driving that might provide a private route to medical care.

And even when companies aren't giving out data willingly, they're doing such a bad job of protecting our personal details that bad people are often getting it anyway. The researchers say they couldn't tell — and companies would not disclose — whether any automaker encrypted all of the personal information that sits on its vehicles, which is considered the absolute bear minimum for data security by experts.

That might help explain why 68 percent of the companies in the study reported a serious leak, breach or hack in the past three years – to say nothing of all the perfectly legal ways that automotive surveillance data can be used to cause harm, like domestic abuse victims who don't know that their controlling partners have set up "boundary alerts" to track their movements when their car leaves the driveway. Tesla, Ford, Lincoln, Mercedes-Benz, Hyundai, Kia, Chevrolet, Buick, GMC, and Cadillac were all found to come equipped with similar location-tracking technology.

For MacDonald, though, the scariest thing is what car companies have yet to do with our personal information — because we've likely only seen the tip of the iceberg so far.

"I'm worried about how car companies plan to leverage the sheer amount of personal data they have, as well as the intimacy of sensor data," she adds. "It feels like sci-fi, but it's really happening."

Get mad and make noise

Of course, for sustainable transportation advocates, securing the data privacy of road users might not seem like the greatest challenge of our time — especially given all the ways that technology could help end traffic violence and make roads more accessible to people across multiple modes. Macdonald stresses, though, that we don't have to reject all data collection to make cars less corrosive to our fundamental privacy rights.

"It can be a challenge to balance privacy and safety, but we shouldn’t be made to feel that they’re at odds with each other," she adds. "For me, the bottom line is that when your data is collected and used it should be for reasons that benefit you: to keep you safer in your car or as you walk down the street. What we found in our research is that your personal data is collected with little or no regard for consent, may often not be adequately protected ... and is being used for reasons that only benefit car companies’ balance sheets."

As someone who lives in a city with good transit and does not regularly drive a car herself, MacDonald says that if any other product they reviewed had such bad privacy ratings as the modern automobile, she would simply advise consumers not to buy it and delete all their data right away. The only automakers in the study that even allowed its customers to delete their data, though, were sold exclusively Europe — and in most of America, few have the option to forgo a car completely.

"Cars are unique in that they're all bad; you really can't trust any of them," she adds. "Automakers will basically do anything they can legally get away with. I think only the natural course of action is to learn about it, get mad about it, and make some noise."

Mozilla is collecting signatures for a petition urging automakers to "stop collecting, sharing and selling our very personal information." Sign it here, and a always, reach out to your reps.