A Democratic governor’s controversial decision to continue a road-widening effort championed by his Republican predecessor is the latest example of leaders of both parties pushing the same old harmful highway projects — raising questions of what it will take to get them to stop.

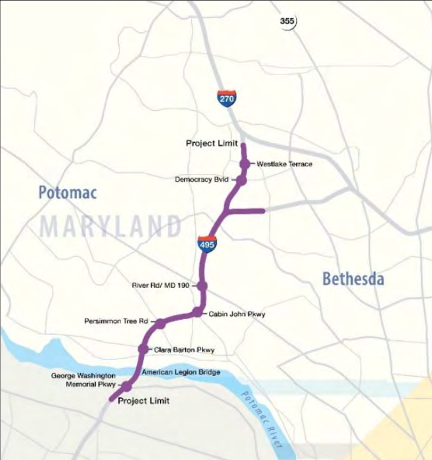

Late last month, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore announced in a press release that his administration would seek federal funding for a slate of new “improvements” aimed at enhancing mobility along interstates 495 and 270. That funding, though, would allocate just three percent of its $4.032-billion budget to sustainable modes while the bulk of the money would fund the addition of two toll lanes in each direction along a segment of I-495, with the possibility of more widening to come at other points along the route at later stages of the project.

And Moore’s press release also didn’t emphasize that the idea for those new lanes came directly from Moore’s Republican predecessor, Larry Hogan, who openly lauded the potential highway expansion in his own 2017 press release for its potential to “reduce congestion for millions of motorists.”

“They’re trying to hide what’s at the center of their plan,” said Janet Gallant, one of the coordinators of the grassroots advocacy group DontWiden270.org.

The Moore administration’s plan isn’t identical to Hogan’s, which at one point ballooned to a budget of $11 billion and relied heavily upon having a private tollway operator design, build, finance, operate, and potentially even maintain the new lanes.

How is a highway expansion in a transit-dense region compatible with the Democratic Party's climate agenda? Note how Md. is basically guaranteeing billions for a proven-to-fail road expansion but only giving unfunded lip service to "push for" more transit. https://t.co/8GsBdMCW88

— David J. Meyer (@dahvnyc) August 21, 2023

Those ambitions, which Hogan claimed would have represented “the largest public private partnership highway project in North America,” were eventually scaled back after outcry from residents. Yet even as the scope of the project shrank, several of its most controversial elements survived, including 15 miles of expanded lanes plus a rebuilt and expanded American Legion Bridge. Maryland transportation officials got the green light to apply for additional federal funding to complete those and other aspects of the project in August 2022, prompting a coalition of advocates led by the Sierra Club to sue (the case is ongoing).

All that seemed poised to change, though, when Moore — who shot to national fame among with the publication of his 2010 memoir The Other Wes Moore — was elected governor just weeks later, prompting hope that the progressive superstar would abandon Hogan’s controversial plan. Instead, a coalition of advocates recently wrote, Moore is relying on a “flawed Record of Decision from the previous administration” — and using the rhetoric of equity and sustainable mobility to win public support for what is still, at the end of the day, a highway-widening.

“Hogan just kept saying, ‘These toll lanes will solve congestion for everyone and cost taxpayers nothing,'” added Gallant. “Gov. Moore, like his predecessor, can’t honestly sell the toll lane plan on its merits, so he has to fall back on smoke and mirrors. His administration is trying to dress up the project as primarily about public transit. But that’s just a marketing ploy and a distraction.”

‘At least [Republicans] tell you what they’re doing’

Highway expansions, of course, have never been the exclusive realm of the GOP — and Moore is far from the first climate- and equity-minded politician to push for one.

“This is something that’s happened across the country, and it happens in states with Democratic governors all the time, even those with strong stances on climate and the environment,” said Ben Crowther, advocacy manager for America Walks, citing recent examples from Colorado, New Jersey, and beyond. “This is a pattern of behavior that cuts across party lines.”

Like Moore’s recent press release, Crowther says Democratic rhetoric around highway expansion projects typically diverts attention away from all the new asphalt to focus on accompanying investments in sustainable modes — even if those investments are comparatively miniscule. He cites as an example Portland’s controversial Rose Quarter “Improvement” Project, which officials have pitched as an opportunity to repair the damage caused to the historically Black Albina neighborhood by capping a few blocks of the interstate that destroyed it decades ago — while simultaneously doubling the width of that same interstate and bringing it even further into residents’ backyards.

“It’s largely greenwashing and equity-washing,” Crowther adds. “We don’t see that sort of rhetoric from Republicans. At least they tell you what they’re actually doing.”

Crowther acknowledges that writing off the $200 million that Maryland has already sunk into studying the Beltway project will be painful, but says canceling the highway widening now will pay far greater dividends to the Free State in the long run. He cites then-Massachusetts Gov. Frank Sargent’s transformative decision to halt the proposed construction of the Inner Belt and South Expressway projects in Boston and Cambridge, which culminated in a dramatic 1970 television address in which we proclaimed that he and other politicians “were wrong” to believe that “highways were the only answer to transportation problems.”

“It’s hard to imagine a politician saying that today,” Crowther adds. “But I wish they would.”

‘A very myopic view’

Attempts at equity-washing have rung particularly hollow in Maryland, where advocates say adding lanes is unlikely to “eliminate employment barriers” for under-served residents as the Moore administration suggests — particularly for families who are too poor to drive. And even for those who do, many of those advocates have been questioning whose congestion, exactly, would be cut.

“The whole theory behind managed toll lanes is that you maintain congestion in the general lanes in order to incentivize people to pay to use the [less-congested] toll lanes,” said Barbara Coufal, chair of Citizens Against Beltway Expansion. “So there are a few people who can afford to be in the toll lanes, and those people will experience congestion relief. But everyone left behind in the general lanes will not.”

And more to the the point, Coufal and her fellow advocates question the very idea that congestion is Maryland’s biggest problem — or that it’s worth exacerbating the state’s other challenges to solve it, particularly in light of which communities are likely to bear the brunt of the burden.

“We are in a climate crisis, and the number one source of climate pollution is the transportation sector,” said Brian O’Malley, president and CEO of the Central Maryland Transportation Alliance. “We also have a lot of public health impacts directly related to both tailpipe emissions and also particulate matter coming off of tires. And we know that the people whose health is most impacted by that tend to be Black and brown communities, and the people who tend to enjoy a near-term benefit when you want when in invest in highway widening tend to be white. [Just saying], ‘We want cars to go faster’ is a very myopic view. And it’s not fair to the people who will be impacted by our failure to look at the whole picture.”

Even if Moore does succeed in appending some multimodal and transit elements onto the project address those concerns, Crowther questions whether it will make much of a difference — or even offset the congestion that’s likely to come roaring back once the law of induced demand kicks in.

“Adding a small bus rapid transit lane is great, but it can’t offset the level of cars that you’re going to continue to put on that road by simultaneously widening the highway,” Crowther adds. “It’s just nibbling around the edges.”

‘This is why these projects stay alive’

Maryland advocates are still hopeful that they can take a bigger bite out of their state’s emissions and equity challenges — if they can convince the Moore administration to consider a broader range of alternatives.

In June, the Sierra Club filed a motion for summary judgement urging the court to vacate the Hogan administration’s Final Environmental Impact Statement upon which much of the current highway-widening scheme is based. Sierra and other groups also continue to urge the governor to “reject this failed proposal from the last administration and develop real solutions to Maryland’s transportation needs” — and give the sustainable options the resources they deserve instead of treating them “almost like window dressing,” as Coufal put it.

“We could do tolling on existing lanes; we could do express buses; we could do all those things and we could repair the bridge,” added O’Malley. “None of those require us to widen [the road].”

Crowther worries, though, that it will take more fundamental reform to defeat highway widenings in Maryland, not to mention the countless other states that are following a similar course. And at the end of the day, it’s not just a matter of politics: it’s a matter of power.

“We’ve done some surveying on this, and eight out of 10 voters know that highway expansions don’t solve congestion,” he adds. “This isn’t any sort of politician’s play for gathering votes; there are special interests involved. The freeway-industrial complex perpetuates itself based on the funding that’s available, and as long as it’s available, politicians will wave the flags of congestion relief and of job creation to get these projects built — even if those jobs are temporary. Really, at the end of the day, it’s about appeasing the highway construction firms, the subdivision developers that build off of highways, the beneficiaries of the autocentric status quo. This is why these projects stay alive.”

Maryland advocates, though, say it’s not too late for their state to chart a better path forward — and they won’t wait until it’s time to vote again.

“[When Moore got elected], he had a perfect opportunity to take a fresh look at the transportation needs of the corridor,” Gallant adds. “And he still has that opportunity.”