With billions of federal dollars promised to reconnect communities torn apart by highways, America could be the brink of one of the largest mobility justice movements in decades. To really right the wrongs of our transportation past, though, author Veronica O. Davis argues we need a new playbook for how to engage and empower the Black, brown and low income communities we harmed the most — and her book, Inclusive Transportation: A Manifesto for Repairing Divided Communities, could be a fantastic candidate.

We sat down with Davis to talk about her deep and diverse experience as a planner, engineer, journalist, and advocate, how to make tough decisions when communities have massive needs, and why an equitable future cannot be car dependent.

Listen below or anywhere else you get your podcasts.

The following excerpt has been edited for clarity and length.

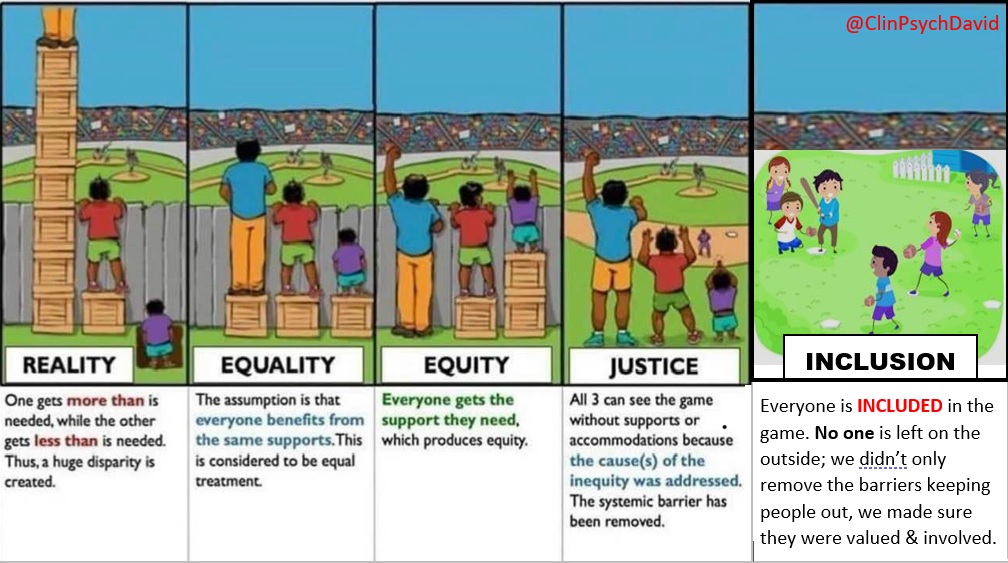

Kea Wilson: I want to take it back to the title of your book, "Inclusive transportation," as well as the term "equitable transportation" and other similar language throughout the book. You reference this famous graphic that I think we've probably all seen of people trying to look over the fence at a baseball game where the short person has a box to stand on but the tall person doesn't — which is fine because both of them can still see it. But you have some criticism of that graphic, because basically, it's a static image that treats equity as an outcome that we arrive at, rather than an ethic that we have to continuously apply. So I would like to hear you just talk a little bit more about why that difference is important. What does it mean to you? What is "equity" the noun? Or maybe the verb? Or can we turn it into a verb?

Veronica O. Davis: Right, and, you know, and that's one of the things — I'm gonna give my big spoiler, I don't really define equity in the book. I tackle it; I tackle the definition. But it's gonna mean different things for different communities and different people.

There are different views of that particular graphic. In an engineering community, someone pointed out that the tall person has to give up their box for the shorter person, and, [they said], 'you know, that's not fair.' People have said, 'why do they even want to see the game? Maybe they want to be the owner of the stadium.'

The reality is, we can't give everybody what they need. And that's the bottom line. Cities cannot give everybody what they need; there is a finite amount of staff, there's a finite amount of time, there's a finite amount of money ... And so what really what it comes down to is prioritization, and that is, prioritizing who needs the most, dealing with that first, and then you eventually, we'll get to everyone.

If we think about an inclusive network —and I talk a little bit about this in the book — we should be building cities for children. A child should be able to confidently move around a neighborhood, a city and feel safe. And that means having places for them to walk, making sure cars aren't driving fast, or are doing all types of things. But a child should be able to walk to the park or walk to school.

And so a lot of that comes down to how we build our communities. In some cases, we've built mega-schools, so kids have to get driven to school. Is that equitable? Because it requires a parent to have a car in order to get their child to school, and think about all the time loss for that parent, waiting in these long, long, long school lines, just to do drop off and pickup ... And if we can accommodate children, if we can accommodate people that may have disabilities, it makes it better for everyone overall.

...

Wilson: For the practitioners in the audience, what are a few of the biggest takeaways you want readers to leave with about what a better community engagement process should look like? And what can advocates in our audience do to get their leaders to take that kind of an approach?

Davis: For the planners and engineers of the world that are doing community engagement, really, it's about what are you trying to get from the community. Because there are going to be projects when there really is no room for discussion. Say we're talking about sidewalks. And if the city's policy or the community's policy is, 'everybody needs to have a sidewalk,' there's really not much to discuss; everyone needs a sidewalk. And this is how we're going to do the sidewalk.

So that type of an engagement is going to be very different. It is going to be, 'this is the law; this is the regulation; here's how we will build the sidewalk, here's how we will communicate with you.' And that is informing. You don't take a process like that and say, 'Hey, tell me what you want to see.'

There are gonna be times where you can have the broader discussion of, hey, we're really open, we know that there's issues here, we have gotten this grant. And we really want to do a planning study to make this a better street.' And so with that, you want to have a very robust engagement process.

So really, it's about tailoring the process to what you're trying to get as an outcome. And be careful not to mix the two. If it is safety, and we're doing it. Don't pretend like you're trying to get to somewhere else and don't do a fake process to get the community to understand that just start off with this is what we're doing and why. And here's where there may be some wiggle room.

For the advocates, I think the important takeaway is on the engagement side, when and how to activate people to be a part of the process. There's a point where you can advocate and be an agitator — after which you might get locked out of the decision-making table. There is a space and there's a time to agitate, but there's also a time where you have to be able to be productive in a way that you are having a seat at the table, to move forward a productive conversation. So it's everything is a balance, and everything is about having multiple tactics in order to get to what is ultimately going to be the project.

To go back to the government side, there are times when we do big, robust public engagement for big projects that we know that are going to be $50 million, $100 million projects. And then we're like, 'okay, great, thank you for all this robust engagement. And we'll see you in five years when we're ready to do construction.' That's a long time for people! It's also about how can we find ways to have something iterative, something to show that, 'hey, here's a good faith effort. Here's something we can do now within our budget, but we are going to come back and do the bigger project later.'