Some of the hottest states in the U.S. have the fewest public drinking fountains per capita, a new study finds — and as temperatures continue break records, it could have big implications for people who walk and bike across the country.

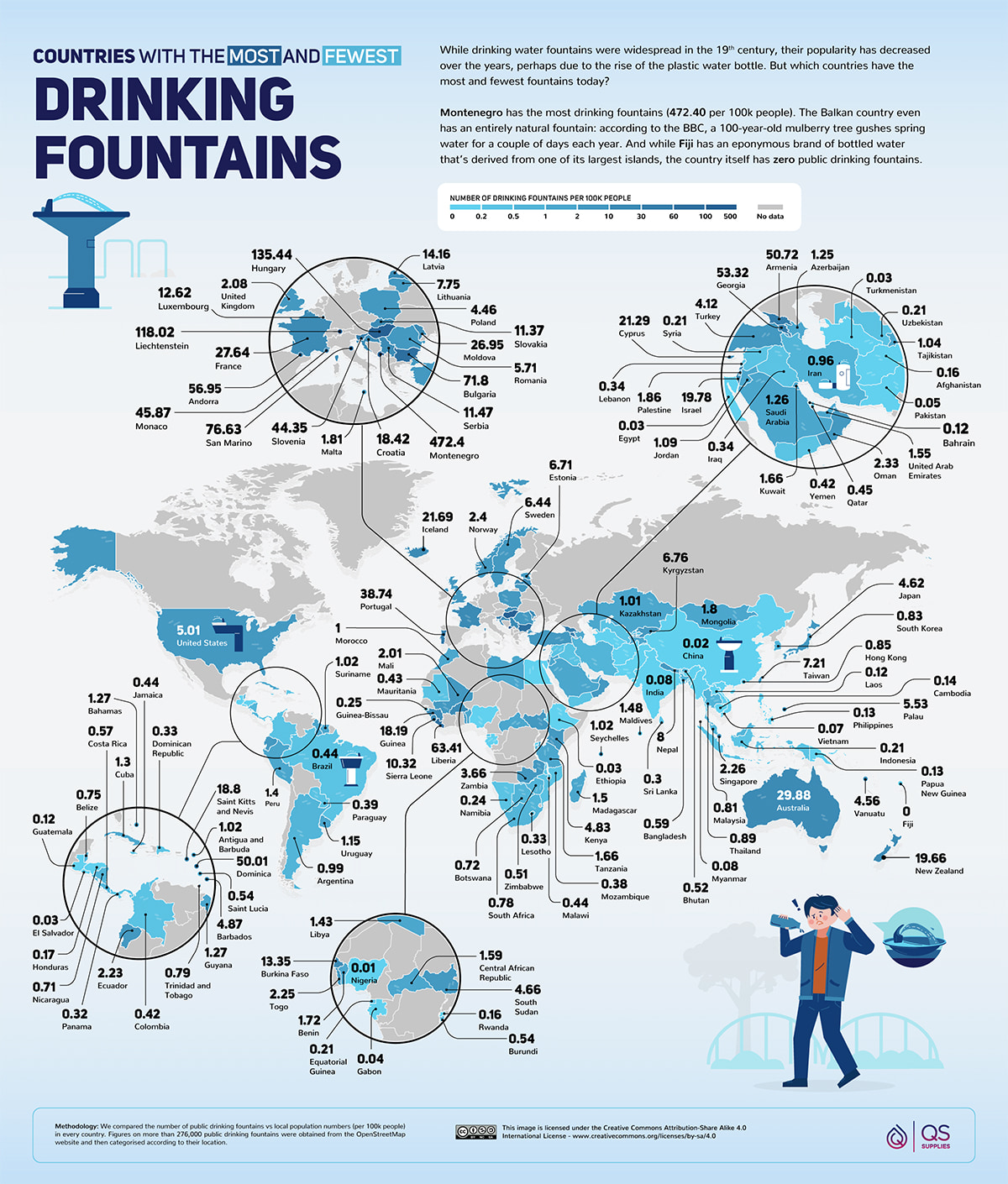

In a new study sponsored by U.K.-based bathroom retailer QS Supplies — yes, they're probably more interested in selling pipe fittings than encouraging sustainable transportation, but still... — analysts estimated that the United States has just five publicly accessible drinking fountains per 100,000 residents, putting America above some European nations like the U.K. (2.1), but way below others, like top-ranking Montenegro (472) and Hungary (135).

"Water and sanitation is recognized by the UN as a human right. ... [Fountain access is] something a lot of built up cities and developed countries are working on at the moment," said Touseef Hussain, marketing and communications officer for QS. "But where did we stand now, there's still a big gap."

Now, the study comes with some caveats. The data behind it was sourced from OpenStreetMap, a massive open-source portal where volunteers from around the world — including, apparently, whole organizations devoted to studying water fountains, specifically — painstakingly analyze aerial imagery to understand global street trends, albeit without the support of traditional research institutions or peer review. The list of 276,000 fountains found by the study authors around the globe couldn't possibly be fully comprehensive, and aerial maps alone can't tell whether fountains are functional, sanitary, or accessible to the thirsty people who need them.

Still, the data hints at a fascinating and under-studied barrier to active transportation on U.S. roads, and it certainly tracks with more established data about car dependency in the United States.

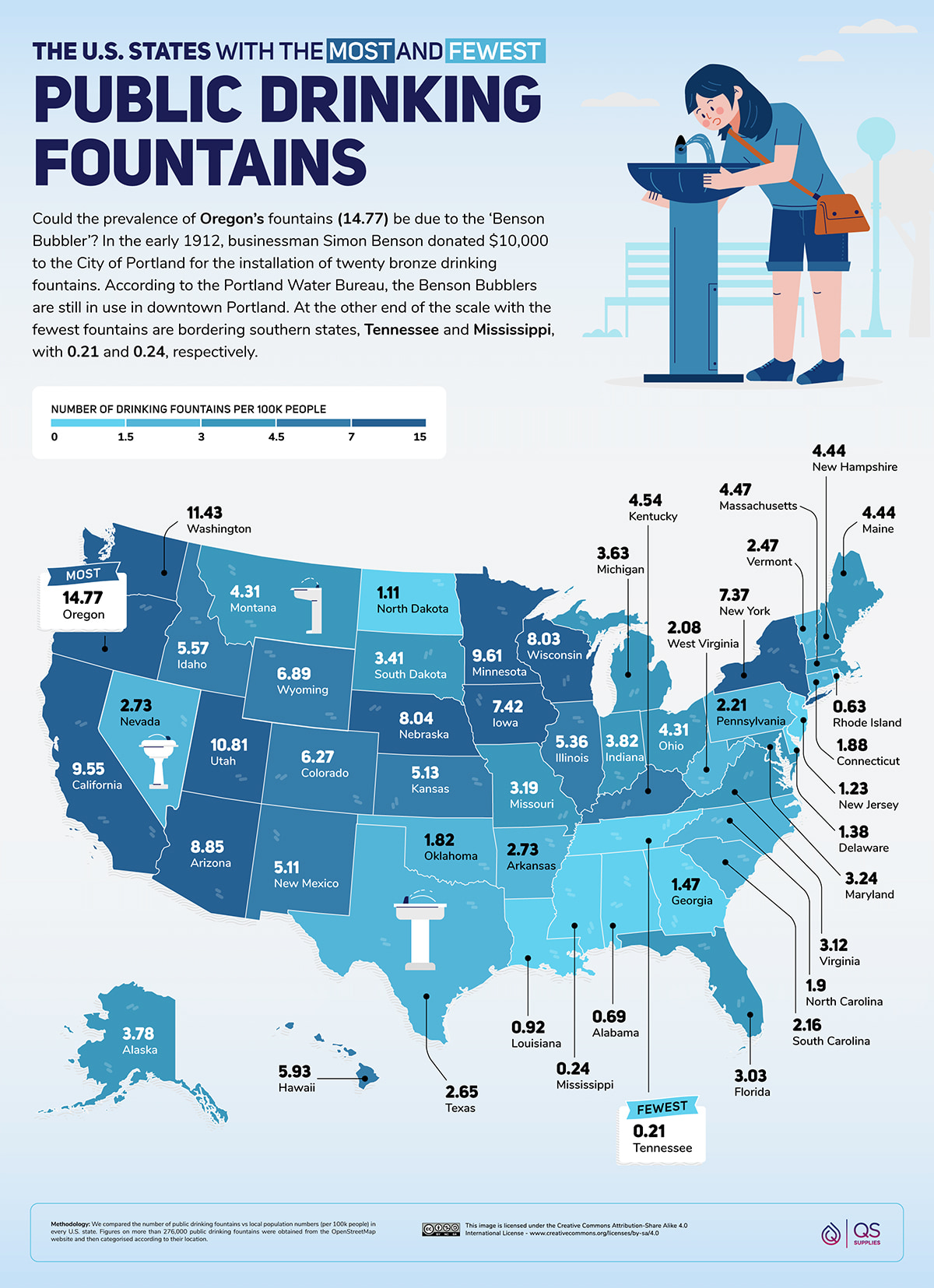

Auto-oriented, Sunbelt states with high rates of pedestrian fatalities tended to rank towards the bottom of the researcher's list of water-rich states, including last-ranked Tennessee (0.21 fountains per 100,000 residents), Mississippi (0.24), Alabama (0.69), and Louisiana (0.92). (Arizona, which is hot enough right now that some of its residents are sustaining severe burns from falling on hot pavement, appears to be the exception, with 8.85).

Meanwhile, pedestrian-friendly and forward-thinking states like top-ranked Oregon (14.77), Washington (11.43), California (9.55) and Minnesota (9.61) tended to rank towards the top.

At the city level, some U.S. communities fared even better, though not nearly as well as their global counterparts. No American city cracked the top 20 most fountain-friendly streetscapes in the world, with impressive Washington, D.C. (24.83 fountains per 100k residents) still boasting only a fraction of the fountains that residents of Zurich enjoy (221.89). Memphis, meanwhile, had just 0.09, which may put it on par with many nations in the developing world that lack access to clean drinking water overall.

What it will actually take to enhance public hydration in U.S. cities, though, remains an open question.

Fountains have long been recognized by researchers as "vital elements in facilitating walking and biking," as urban designer Josselyn Ivanov once wrote, but their role in encouraging active transportation seemingly hasn't been studied much. Extreme weather events like heatwaves, though, are perennially recognized as major barriers to active travel, and design groups like NACTO frequently cite public fountains among the street design elements that send a clear signal that a place is built for people rather than cars.

At the policy level, though, street-side fountains haven't gotten much attention in local zoning or health codes, apart from a handful of bills aimed at increasing access to them in places like parks, playgrounds and libraries. For car-oriented US cities with few of any of those, though, that means water may be hard to find on the go without stopping inside a private business that may not welcome patrons who can't pay — a particular problem for the unhoused. And needless to say, fountains became even more scarce in the early days of the pandemic, when many cities shut them down over fears that the disease could be transmitted through surfaces, even as climate change sent temperatures skyrocketing in urban heat islands.

In a handful of U.S. cities like Portland, though, the ubiquity of free fountains have become a point of civic pride. The City of Roses brags about its 80 "iconic Benson Bubblers" scattered throughout the downtown core, about 50 of which feature enough spouts to allow four people to drink from them simultaneously. (Curiously, Oregon's ranking also gets a boost from its famous highway-side fountains, which were built in the 1930s and geared towards road tripping drivers pausing to take in the views)

Zurich, meanwhile, hosts whole pedestrian tours to celebrate the 12,000 drinking fountains stationed "every few meters" throughout its streets — and not only because its ancient residents once relied on them in the days before private indoor plumbing.

"A lot of the fountains in cities like Zurich they date back to hundreds of years ago, when this was just part of the infrastructure, and this is what all the locals would use," added Houssain. "But the difference with Switzerland is that they have kept up the maintenance of these structures, and they've also implemented newer ones."

Houssain stresses that increasing street side water access could carry benefits far beyond the transportation realm, since they can drastically reduce plastic bottle waste and even double as stunning historic landmarks and public art. At the minimum, though, he hopes that no one will trade a car trip for a short stroll or cycle simply because they don't want to lug around a water bottle to stay cool — and that cities will support them by putting fountains everywhere.

"I think the more that people start to realize [the importance of drinking fountains], the more we can start to get governments and private institutions thinking about this what more we can do to make them widely available," he added. "This should become a key, everyday part of our lives."