On June 15, the state of Florida sentenced 40-year-old Gregory Andriotis to a total of 30 years prison, the state-allowed maximum — and what some advocates against distracted driving believe is the single longest sentence for the crime of using a phone behind the wheel in U.S. history.

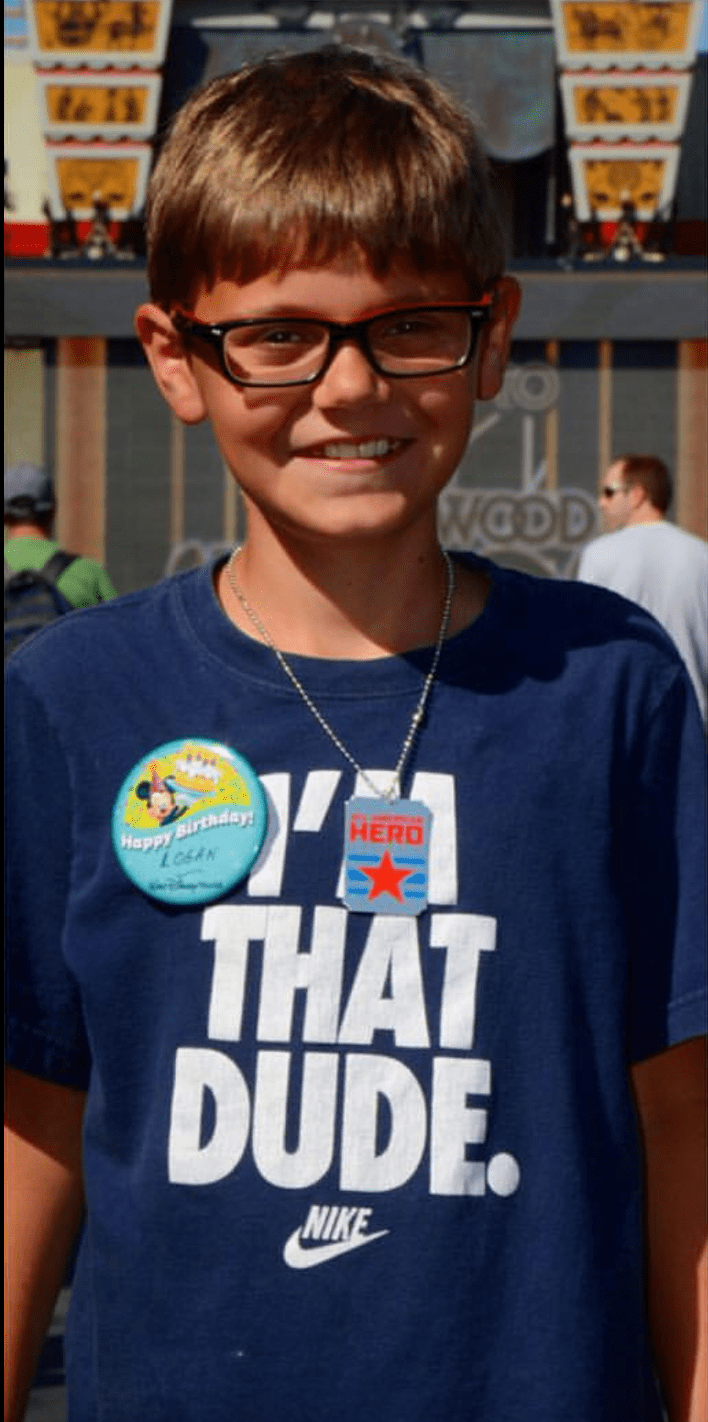

In the eyes of the law, the sentence represented long-awaited justice for the 2016 death of nine-year-old Logan Scherer, who perished instantly when Andriotis slammed into the back of his parents' Mazda at around 85 miles per hour on a Florida highway. It also represented justice for the devastating injuries he caused to the other occupants of the car: Logan's mother and father, Brooke and Jordan, collectively spent weeks in the hospital recovering from punctured lungs and serious head injuries, while his then-five-year-old sister, Mallory had her legs broken so badly that they needed to be reinforced with titanium rods. Fifteen years of Andriotis's sentence are for vehicular homicide; the other fifteen are for three counts of reckless driving with serious bodily injury.

Over the course of grueling, seven-year legal battle, forensic investigators ultimately determined that Andriotis had been so distracted by his phone for so long at the time of the crash that he had actually accelerated into the family's SUV in front of him in the moments before impact, failing to notice the taillights of roughly three miles worth of cars stopped in traffic directly in front of him. While he wasn't sending text messages — a deadly behavior that wasn't fully illegal in Florida until 2020 — the Scherers said he had done "just about everything else" with his phone that day, including making multiple calls, getting directions, paying a credit card bill, surfing the web, and even downloading and opening the Excel spreadsheets app. Excel was still open on Andriotis's phone in the instant before impact; he did not attempt to swerve.

For advocates working to end traffic violence, though, the question of whether justice was truly served by Andriotis's sentence is more complicated — and even the Scherers themselves hesitate to call it an outright victory.

"I don't think we really won; we didn't win," said Jordan. "He got 30 years, but we have a lifetime sentence because of Logan's loss. And we’re just now coming to grips with understanding what that means."

'If it's so dangerous, why isn't it illegal?'

Andriotis's sentence isn't remarkable only for its sheer length. It's remarkable that it even happened at all.

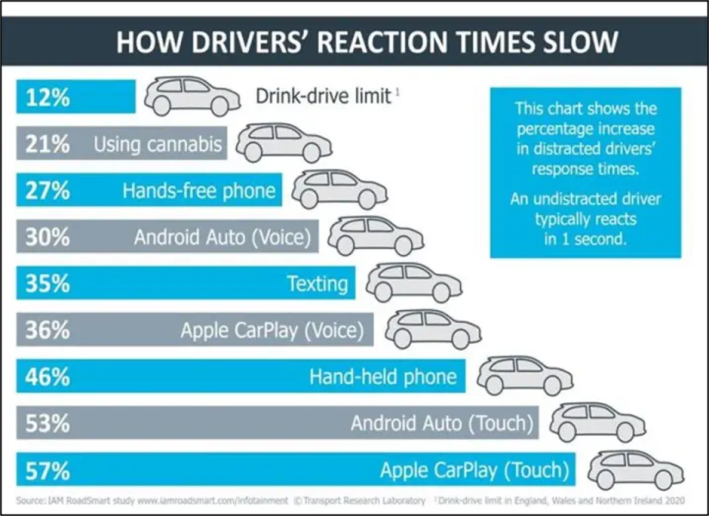

Despite decades of research that's shown using a phone behind the wheel to be just as impairing as drinking alcohol, distracted driving laws across the U.S. remain a confusing patchwork rife with community-specific carveouts not afforded to those who drive under the influence of liquor. Some states still only allow a motorist to be cited for using cell phone after they've been caught committing another roadway crime while doing it, often when someone's already gotten hurt. Others ban "texting" behind the wheel, but don't explicitly ban using phones for other purposes, like scrolling through social media. Most still permit the use of devices on hands-free mode, despite the fact that some researchers believe that's just as distracting as using a cell phone manually.

In Florida, where Logan Scherer died, drivers are still legally allowed to text when the vehicle is stopped, or to use navigation apps, among a range of other exceptions that Polk County Sheriff Grady Jed said often made the law functionally unenforceable — or, as he once colorfully told local media, "not worth the mammary glands on a boar hog."

Even in the states with the strongest policies on the books, researchers believe distracted driving is still vastly underreported and under-represented among the charges that dangerous drivers actually receive. Officers don't always bother to investigate whether distraction was a factor, particularly when no one actually witnessed the driver holding for a device. Cops often have no legal recourse to seize a driver's phone at the scene, and struggle to access expensive forensics to recover hard evidence of distraction later.

Even years after Logan Scherer's death, Florida law enforcement officers are still explicitly required to tell motorists suspected of distracted driving that they don’t have to hand over their phones to police if they don't want to. Gregory Andriotis didn't do so when he was stopped, though he openly admitted to officers that he had been using his device.

"When Andriotis hit us, he knew well enough to say he wasn’t drinking – but did he felt comfortable saying 'I was on my phone,'" added Brooke. "But his phone was never taken. There was no law, there was no [legal justification] for them to physically take his phone. It wasn’t until Jordan and I started down the litigation process that his phone was actually seized. And it took years for us to get those forensics."

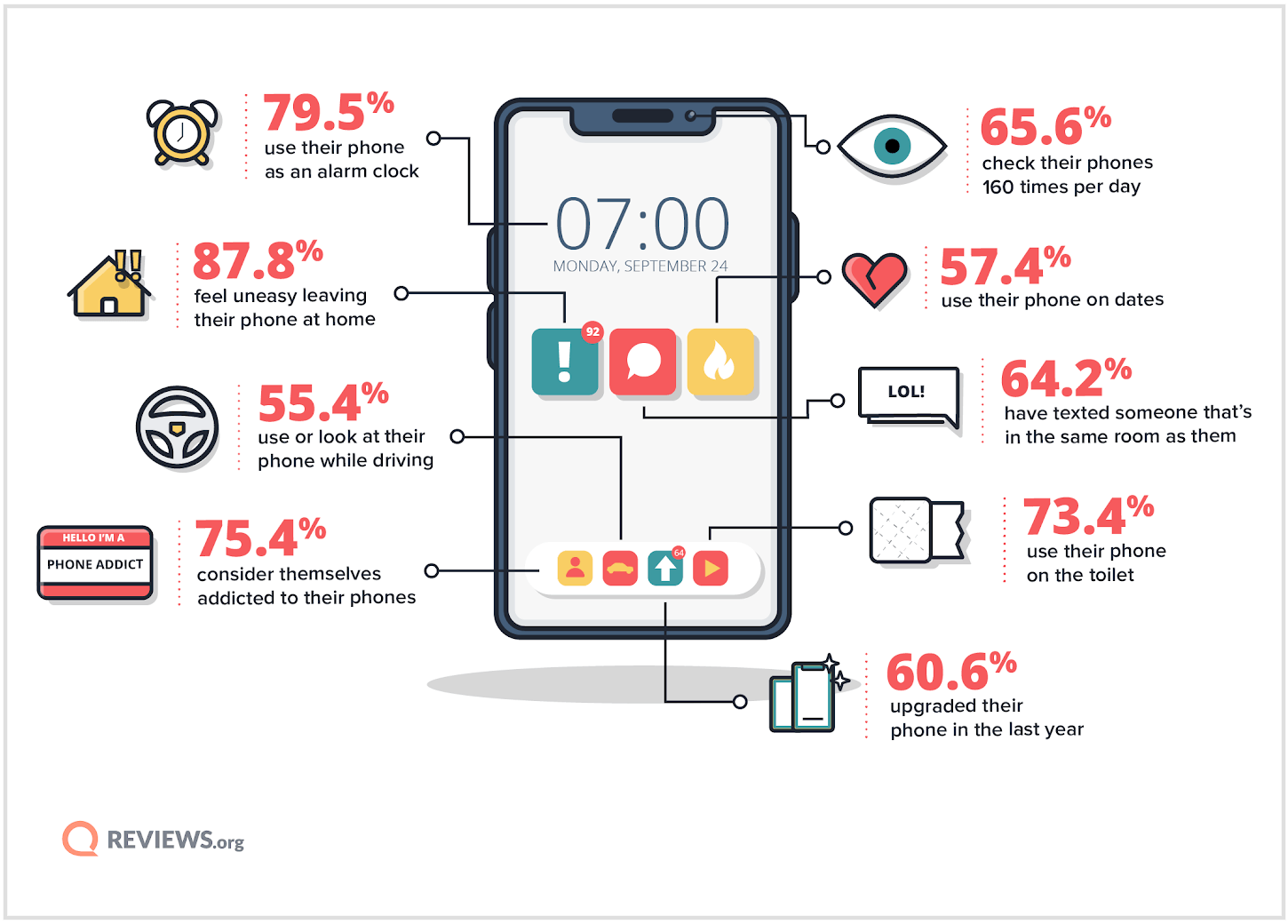

Amid this dizzying web of legal exceptions, some advocates argue, a social perception that distracted driving is okay has taken root. Today, 54 percent of US motorists still believe it's safe to use a hand-held phone behind the wheel — and 51 percent openly admit to having done it in the last year. Other surveys put the total closer to 70 percent.

"We go into high schools and tell them that distracted driving is dangerous, and the kids say, 'well, if it's so dangerous, why isn't it always illegal?'" said Jennifer Smith, CEO and co-founder of the nonprofit Stop Distractions. "I think they've got a point."

Choice or addiction?

If the vast majority of Americans agree that distracted driving should be illegal, the question of who should ultimately be held responsible is still up for debate — at least among some corners of the mobility justice movement.

Much like drunk driving, some advocates argue, Americans don't only use their phones behind the wheel because they have any "wanton, willful disregard" for the lives of other road users, as the sentencing judge said of Gregory Andriotis. Many of them do it because they'e functionally addicted to a device that's specifically engineered by multibillion dollar corporations to keep and hold their attention at all costs. For others, using phones while driving is a necessity of demanding jobs, or because they fear our hyper-connected capitalist society on the whole will penalize them if they fail to be constantly reachable, even when they're hurtling down the road at 80 miles an hour. And some undoubtedly do it because automakers have literally embedded the internet into dashboards and marketed constant connectivity as a luxury feature, rather than a safety threat that increases the risk of a crash or near- miss by a factor of 23.

"Smartphones are the most intimate devices we have,” said Jonathan Matus, founder of driving analytics firm Zendrive, in an interview with AARP. “We have a dependency on them. They are an extension of our intellect, they are an extension of our social network, they get us from point A to point B, they entertain us. The habit is so strong."

From that standpoint, some advocates argue, the answer to distracted driving isn't harsher laws that throw the Gregory Andriotises of the world in jail after they've taken the life of a child — not to mention providing yet another pretext for police stops that could turn deadly, particularly when Black motorists are involved, as the American Civil Liberties Union has repeatedly argued. It's structural solutions aimed at stopping distracted driving before it happens, like getting the cell phone out of the dashboard, or making Do Not Disturb While Driving mode less comically easy to disable outside of a true emergency.

"The imposition of legal liability on the distracted driver likely does have an impact on other drivers, and likely causes some of them to turn off their cell phones when they get in their vehicles," wrote MIT professors Nicholas Ashford and Charles Caldart in a 2022 essay. "[But] this remains a piecemeal response to an issue that cries out for a more systemic approach."

Smith is sympathetic to that point of view — to a point. While she disputes the idea that extremely distracted drivers like Andriotis are simply victims of bad policy rather than a people who made bad choices, she says her group does support research into the psychology of distracted driving more broadly, as well as a range of technological strategies to eliminate it.

But after decades of advocacy following the death of her own mother in a distracted driving crash, she has less faith that automakers and cell phone providers will actually allow those solutions past the gate — at least while they're still profiting off of keeping Americans plugged in and tuned out.

"They won't do it," Smith adds bluntly.

Cutting into the distracted driver problem

What Smith has seen work during her long advocacy career, though, are strong laws. She cites research that shows that passing laws that allow only hands-free cell phone have resulted in reduced crash rates of about 13 percent a year on average, a modest but meaningful shift that equates to about 100 saved lives.

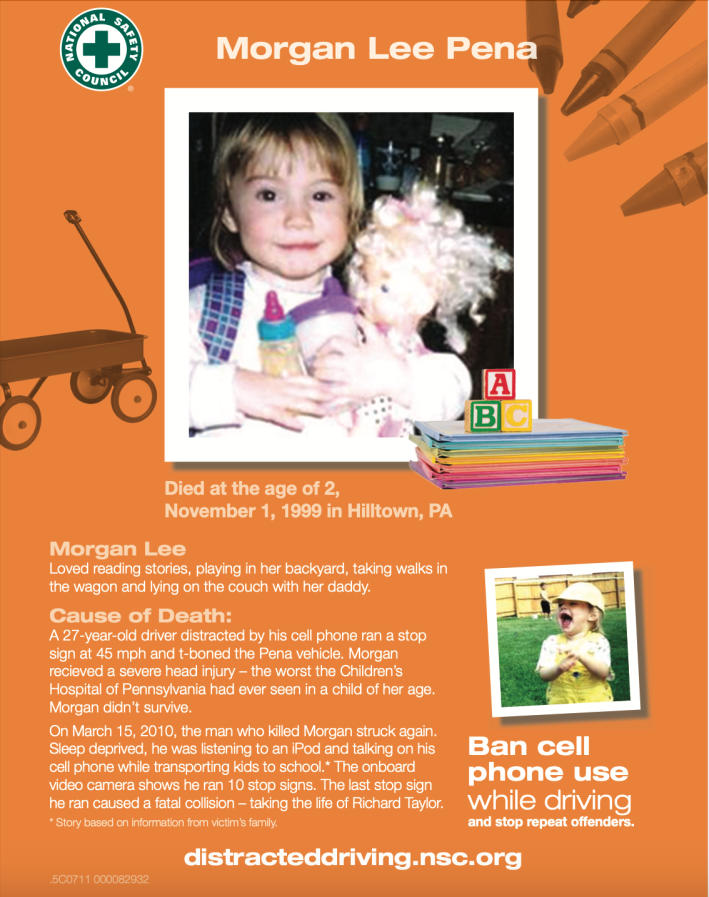

And she also cites cases where distracted drivers were let off with little more than a slap on a wrist, only to kill again. That's what happened in the 1999 death of two year-old Morgan Lee Pena, whose killer, Frederick Poust, received only minor citations for careless driving and failing to stop at stop sign, despite the fact that he was found to have been using his phone when he struck the car in which the toddler sat. (Those citations are eerily similar to the ones Gregory Andriotis initially received after the death of Logan Scherer; at the time, he received only a small fine, a one-year license suspension, and community service, before the family pursued more serious charges.) When Poust killed 27 year-old Richard "Trip" Taylor ten years later, he was behind the wheel of a school bus packed with 45 children, which he'd been hired to drive in part because his driving record came up clean; he was also talking on his phone via a wireless headset, which had distracted him so much that he rolled through ten consecutive stop signs.

His sentence in the second crash was one to two years, plus five years probation — after which, some might argue, he may very well do it again.

For the Scherers, though, Andriotis's long sentence isn't just about keeping one extremely dangerous driver from killing again. If that were the case, they may not have have stuck out the seven grueling years they spent re-living the horror of their son's loss in countless courtrooms, a process so emotionally taxing they eventually left their lives and jobs in Florida to be closer to family in Indiana and check into residential programs for trauma treatment. Rather, they hope the sentence sets a strong legal precedent in the Sunshine State that might encourage other drivers to put their phones down — and a social precedent that might soften the ground for more systemic solutions.

Still, as they stood in the courtroom to hear Andriotis's sentence two weeks after what should have been their son's 16th birthday, they did not feel a sense of victory.

"If there’s something in our story that can be labeled a 'win', it’s that hopefully, other families will never have to go through this battle," added Jordan. "We don’t want anyone to lose a loved one due to someone else’s lack of concern for others ... Everyone has a phone. Everyone has some way to get distracted behind the wheel. Even Brooke and I used to do this; we’d never say we’re holier than thou. We just have to change the way this is looked at by people. We have to change what's considered normal."

Jennifer Smith couldn't agree more.

"We hope no one ever goes to jail [for distracted driving] again, because we hope no one ever drives distracted again," she adds. "That would make it all worth it. That's why we do this — so your loved ones come home to you alive. Because for our loved ones, it's too late."