About that electric vehicle revolution...

Residents of poor neighborhoods got a double-whammy from California's so-called "Clean Vehicle Rebate Project": they were much less likely to take advantage of the program, and their neighborhoods experienced far fewer emissions reductions from electric cars than wealthy ones, according to a new study by researchers from three esteemed universities.

To be clear, the rebate program did reduce overall statewide emissions of carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide between 2010 and 2021, the study period. But the program also increased aggregate statewide emissions of primary PM2.5 [a fine particulate that gets into the lungs].

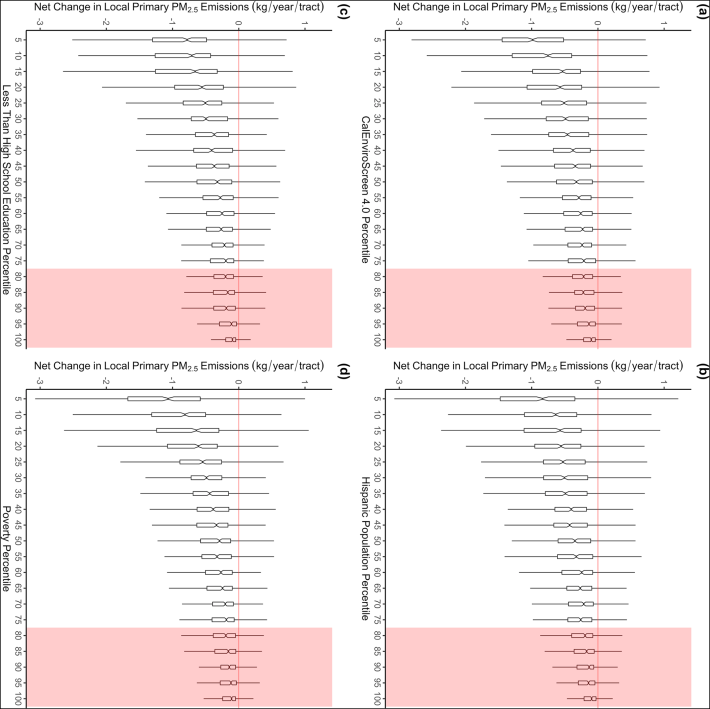

And, researchers found, any decrease in particulates, NOx, and SO2 "disproportionately occur in Least Disadvantaged Communities, as compared to Disadvantaged Communities."

The problem is where California produces electricity in the first place.

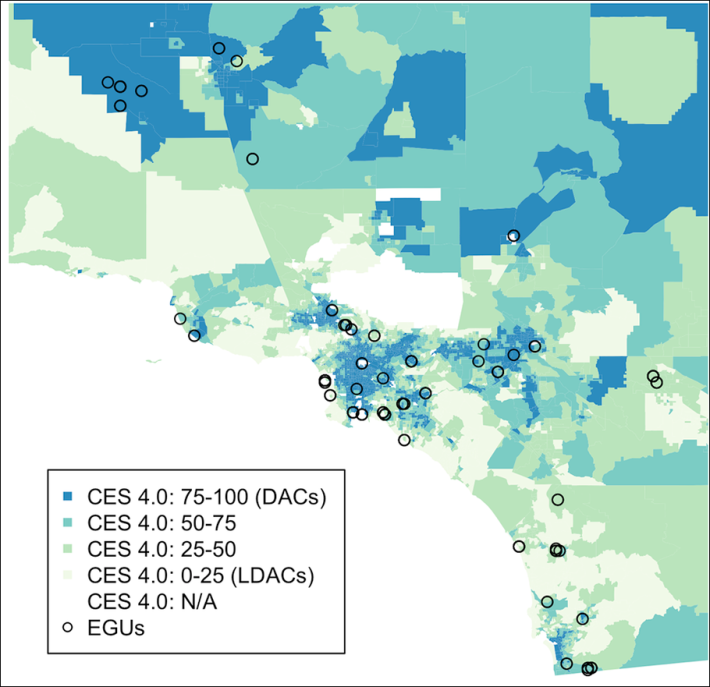

"Increased electricity generation to support new electric vehicles introduces possible redistribution of point-source emissions from mobile vehicles to electric generating units such that emissions may decrease in some locations and increase in others, with implications for equity," wrote authors Jaye Mejía-Duwan (of University of California–Berkeley), Miyuki Hino (University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, and Katharine Mach (University of Miami).

"If the current spatial distribution of electric vehicle rebates remains unchanged, we project that these inequities will continue through the state’s legislative goal of 1.5 million zero-emission vehicles on California roadways by 2025, even with increased cleanliness of the electricity sources for new vehicles," the study continued. "Increased uptake of electric vehicles in communities facing the highest air pollution exposure, along with accelerated clean-energy generation, could ameliorate associated environmental inequities.

The rebate program was established in 2010 with the goal of stimulating the purchase of electric vehicles, which supporters claim reduce pollution (though the benefits are not entirely clear). California issued 400,000 rebates in the 12 years of the study program, with the rebates reaching $7,000, depending on the value of the car and the applicant's income level. The program is growing, expecting to dispense another 325,000 rebates through next June.

Regardless of pollution, such rebate programs have shown to be enjoyed more by the rich than by the poor, Streetsblog MASS and Streetsblog NYC previously reported. In New York State, for example, the richest 30 percent took in 62 percent of all electric car rebate checks while the bottom 50 percent of state earners collected just 21 percent of the benefits.

White suburbanites benefitted the most from Massachusettes' program, Streetsblog reported.

The same seems to be true in California, where "the price of an EV, even with an incentive, is out of range for many California residents," Streetsblog CAL reported. And the authors of the new study agree, finding that only 5.9 percent of rebates went to residents of disadvantaged communities versus 52 percent to residents of what California calls "Least Disadvantaged Communities." Even after the program was tweaked in 2016, the numbers only changed to 8.25 percent and 42 percent.

"Rebates through the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project are expected to improve local air quality in and surrounding the census tracts in which the rebates are issued," the study said. "However, significant disparities exist in the distribution of electric vehicle rebates, largely related to demographic and socioeconomic factors."

The authors emphasized that electric cars had an overall positive for air quality across the state, largely due to the state's wide use of renewable energy sources "and the limited contribution of coal to the energy mix" — conditions that are not as positive elsewhere in the country. But on a local level, some areas will get much cleaner much faster due to "local factors related to regional electricity generation [and] the spatial distribution of electric vehicle uptake."

The particulates that cause respiratory ailments are another matter entirely: "Aggregate increases in PM2.5 emissions ... are possible because vehicle electrification only minimally reduces vehicular PM2.5 emissions, while at the same time energy generating [facilities] meeting increased electric demand may increase their production of PM2.5 emissions."

Currently, on-road motor vehicles are responsible for nearly 33 percent of human caused NOx emissions, 5.6 percent of SOx emissions, and 7 percent of PM2.5 emissions.

And, lest electric car supporters forget, EVs aren't really much better at reducing particulates, cutting them by only 1 to 3 percent from internal combustion engine vehicles. It's counter-intuitive, the researchers said, but the heavier weight of electric vehicles increases PM2.5 emissions from brake wear, tire wear and road wear. Plus, "heavier EVs, equipped with large battery packs to support a driving range in excess of 300 miles, actually have total vehicular PM2.5 emissions that are 3- to 8-percent higher than internal combustion engine vehicles."

A study in Spain found that 40 percent vehicle electrification yielded only a 5- to 7-percent reduction in PM2.5 emissions. Performance was far worse in 34 Chinese cities, a study found, with particulates increasing by a factor of 19, but that was largely due to the high use of coal in China.

In California, energy plants are disproportionately located in disadvantaged communities, the authors said.

"Our results are consistent with estimates that vehicle electrification programs may disproportionately redistribute air pollution impacts towards disadvantaged communities, even in markets like California that are often considered prime candidates for electrification," the authors concluded. "Additional effort is required to ameliorate the inequitable distribution of costs and benefits of California’s current climate policy."