Montgomery County is going big on BRT — or at least it hopes to.

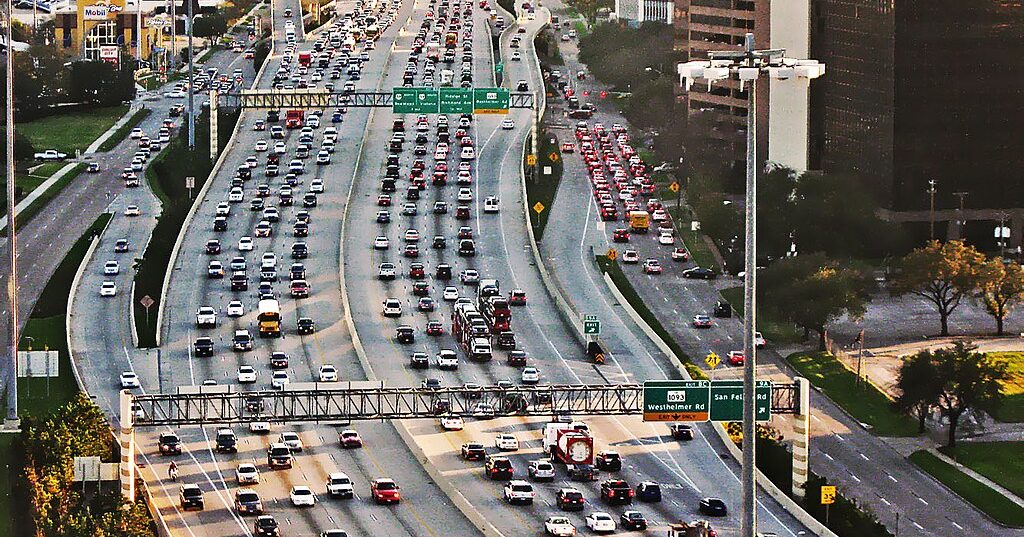

The built environment of the Maryland suburb is sprawling, congested, and plagued by traffic violence — like most American suburbs. But the county of over one million people is racing to create a transit network that meets the moment and anticipates more growth still — and a system that’s foreign to most Americans.

True bus rapid transit consists of dedicated bus lanes and off-bus fare collection among other key definitions things. Regardless of the specific design, BRT is an upgrade from traditional bus service, an effort to augment road infrastructure to skirt traffic, increase reliability, and effectively approximate a train.

It’s astronomically cheaper than a heavy rail subway, and in the case of Montgomery County, it can enhance and fill in gaps for existing area rail service. Adding to the urgency, Montgomery County is vying for a stronger share of the D.C. area’s economic prosperity. Fairfax, Loudoun, and Arlington Counties in Virginia — all among the 10 wealthiest in America — have outperformed Montgomery County in recent decades, with Arlington County even beating out Montgomery for the Amazon HQ2 project in 2018, a success that many attribute to better transit connectivity.

Now, many in Montgomery County are saying that BRT is a better investment than widening Interstates 270 and 495 (already 12 and eight lanes, respectively).

“People recognize that if Montgomery County is going to be able to do economic development, we need a different model,” said County Executive Marc Elrich, a Democrat. “It's an ongoing issue that if you can't move people, nobody's going to come there … to businesses, transportation matters because it's delivery of customers and delivery of employees. So if your employees are stuck on the dysfunctional road network, you have trouble keeping them.”

Montgomery County already has two branches of the D.C. subway's Red Line, a commuter line, one BRT line, and the under-construction Purple Line, a light rail once conceived as BRT.

Elrich said that the county’s decades-long conversation about BRT “tells the story of what the difference is between Montgomery County and Northern Virginia in a lot of ways because Northern Virginia made major investments in transit that the county was never able to make.”

A 2021 D.C. report shows that Montgomery County has the lowest estimated tax burdens for small and large corporations in the region. Elrich noted that Virginia municipalities leveraged that extra tax revenue to fund transit projects, and that it’s paying off.

“Not being stupid, [Northern Virginia] realized that infrastructure was kind of the key to being able to attract development,” Elrich said. “Everybody used to refer to Tyson's [Corner] as a total mess … it was like all this sea of parking and congested as hell and nobody wanted to be there. And then they build the Silver Line and they're hailed as being visionary.”

Not to be outdone, Elrich is looking to implement an expansive BRT plan that would be among the nation’s largest. The county issued a BRT master plan in 2013 calling for 80-100 miles of BRT. Ten years later, one BRT line is in operation but only has dedicated lanes for part of its route.

Montgomery County Department of Transportation Director Chris Conklin and BRT Project Manager Corey Pitts explained in an interview that additional improvements are underway — two additional corridors are in the design phase and are funded to completion, for example — and that the master plan itself envisioned gradual implementation in the first place.

As for the rest of the network, Pitts said that he and his team are calling for more funding with each budget cycle. Elrich’s FY24 budget called for over $500 million in six-year bonds earmarked for transit, but it remains an uphill fight against the status quo.

Take lobbyist Steve Silverman, who represents development interests. A former member of the Montgomery County Council, Silverman questions why businesses should carry a Fairfax County-style tax burden while, he claims, “the jury is out on what the BRT system will ultimately look like and who's going to pay for it.”

Silverman said the business community supported both the Intercounty Connector (a freeway project) and the Purple Line, but argues that there isn’t enough scrutiny of Elrich’s BRT ambitions.

“No one is stepping back to take a look at whether all of the routes that are planned are necessary,” Silverman said. “For example, there's supposed to be a BRT on Rockville Pike. It parallels the Metro, so what is the purpose of the BRT on Rockville Pike if there's already a transit option?”

He claimed that a lot of county residents aren’t interested in the plan as it stands.

“Folks who live up in Germantown are more interested in understanding whether there is a transit line that will serve them, or frankly, another lane or two on [I-270],” Silverman said. “The business community has always supported and will continue to support transportation infrastructure, but it has to be something that people agree should be done. And that conversation has not taken place.”

Conklin said that the county has engaged in general education and outreach on BRT since 2015 and that the plan has enjoyed support from elected officials and the public. But, Conklin added, “that doesn't mean that they're all going to be supportive all the time. … That doesn't mean that there aren't folks who still feel we need more investment in road capacity.”

So how do governments make the case for BRT? To an extent, Elrich believes that a good product will sell itself, saying that BRT has worked everywhere it’s been done. On Montgomery County’s existing BRT line, engineers intentionally built bus stops that communities would value as civic architecture and that the buses themselves stand out from the rest of the fleet.

Elrich has even bigger visions of single-driver, five-vehicle-long bus platoons on the county’s five planned trunk lines. But first comes opening day. Pre-empting anxieties about leveraging corporate taxes to get to the finish line, Elrich insisted, “We're not going to be the highest taxed [municipality], Virginia is well ahead of us. Don't worry about it because we're not building a subway system, we'll never have to go as high as Virginia went.”

As for getting to that point, Elrich said, “[That] is where a little political courage is needed.”