A new Colorado program is seeking to curb crime by investing in safer, more accessible streets — and not just the crimes committed by drivers.

Earlier this year, criminal justice officials in the Centennial State began the Crime Prevention Through Safer Streets program, a first-of-its-kind grant initiative which offered communities a total of $6.2 million for targeted projects aimed at bringing crime rates down. Unlike most of the department's programs, though, that money could only be used on physical infrastructure like sidewalk improvements, lighting, school bus stops, and their maintenance — and couldn't be used on cops, or even automated enforcement cameras.

That approach, the leaders behind the project hope, will not just keep vulnerable road users safe from roadway crimes, but help prevent violent ones like robberies — before police are called.

"From a philosophical perspective, a lot of people might ask, 'Well, does making things "pretty" really impact crime?'" said Debbie Oldenettel, deputy director of the Colorado Division of Criminal Justice. "But it's really more about doing essential things that may seem small — having a good sidewalk, having it be accessible to all, having lighting on it — to help encourage a sense of community and ownership and vitality. Ultimately, that translates into more people— and fewer opportunities for crime to occur."

The new program was inspired by the decades-old model of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design — known by proponents as CPTED — an influential and controversial public safety approach built on the idea that poorly maintained public spaces invites poor behavior among the people who use them.

Rather than surveilling, fining, and arresting residents for having broken windows though, proponents of more progressive forms of CPTED argue that the model can be used to advocate for community-led investments into "blighted" neighborhoods, like assistance programs to help residents fix broken windows for free — along with fixing broken sidewalks, replacing absent streetlights, and re-painting faded crosswalks.

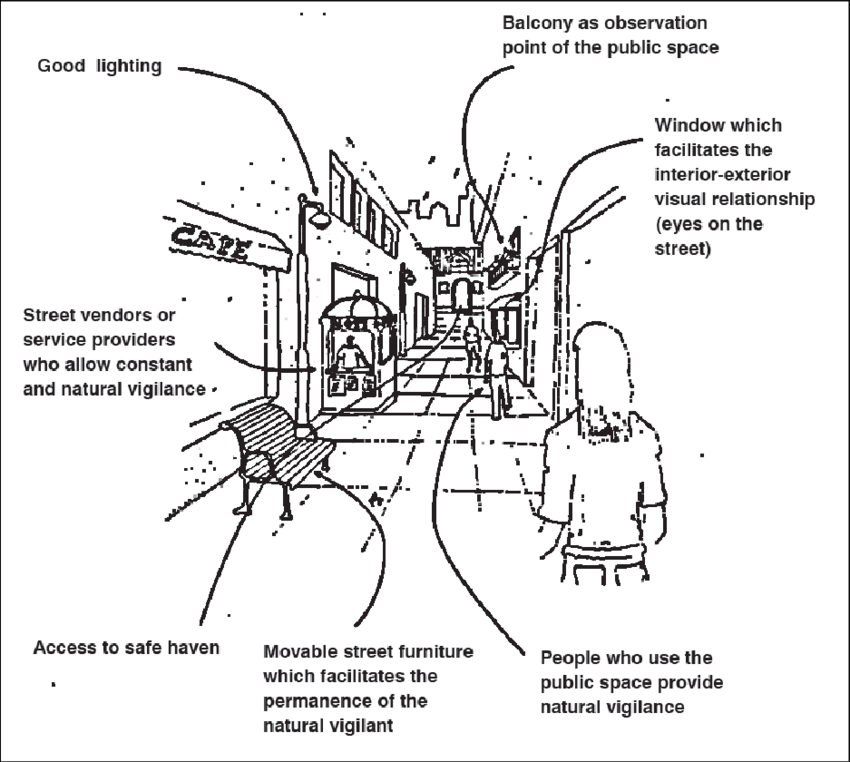

And CPTED supporters say those types of basic maintenance don't just provide the immediate benefit of getting a pedestrian out of the driving lane or making sure a motorist can see her at night. They also send a powerful, tacit message that this is a place that people are looking after, and that encourage neighbors to spend time outside their homes and businesses — thus creating places where crimes are likely to be witnessed by "eyes on the street," even without surveillance cameras and armed police patrolling the block.

"You can have 99 percent of the built environment designed to NACTO standards, and if the place isn't cared for, people may still blow through the traffic circle and mow down the 'slow down' sign," said Ignacio Correa-Ortiz, an architect and urban designer who helped advise the administrators of the Colorado program. "It’s the candy wrapper syndrome; if you drop a candy wrapper, and nobody picks it up, the next person then goes by will be more likely to do the same, and then it will incrementally get worse."

Many of the Colorado grantees' projects specifically focus on maintenance projects that double as accessibility upgrades, like trimming back overgrown vegetation on a downtown riverwalk or improving street side trash collection. Street lighting is also a major theme, both along roadsides — 76 percent of pedestrian deaths happen in dark lighting conditions — as well as in in parks and other public spaces that often double as active transportation routes.

Critically, the project administrators say they took care not to fund projects that would be beneficial to the larger community at the expense of its vulnerable, which many CPTED programs have been criticized for in the past. That means that "hostile architecture" strategies, like benches and curbs designed to discourage unhoused people from merely sitting for too long, were excluded; projects that use fences to limit access to public space, meanwhile, were chosen carefully, such as a Colorado Springs effort which will close a park to vehicle traffic at night, but leave it open for everyone else.

"We didn’t want to fund any projects that would infringe on the civil liberties of people," Correa-Ortiz adds. "This is more about helping communities to police themselves — in the good sense of the word 'policing,' which is about creating a 'polity' and a sense of community ownership."

Correa-Ortiz stresses that CPTED alone isn't enough to deter, or even displace, all forms of crime, and it's definitely not a panacea for unhoused populations, who need access to shelter and services that programs like this don't provide. And he's also sensitive to other critics of CPTED like cultural anthropologist Nathaniel Adams, who wrote in a recent op-ed that the model "fails to address the persistent inequity at the heart of these problems," and focuses too much on curbing criminalized behaviors, rather than "interrogat[ing], challeng[ing], and transform[ing] unequal social and economic structures" that are associated with high crime rates, particularly in communities of color.

If the Colorado program is successful, though, it could spark a conversation about how design could be used to make communities safer when wielded alongside deeper structural reforms — or at least provide some alternative to more conventional forms of policing.

"This piece of looking at the built environment, while it’s been around for a while, it’s not one that I, in my years of working within the criminal justice system, that I’ve seen a lot of energy put into," said Oldenettel. "This is not a typical approach."