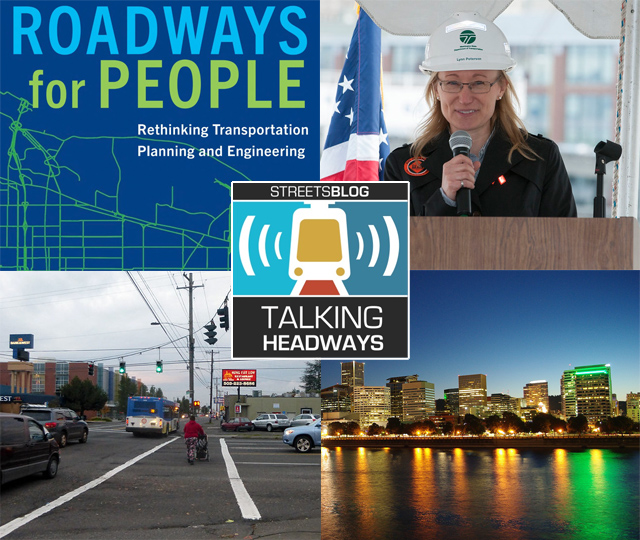

This week we’re joined by Oregon Metro Council President Lynn Peterson to talk about her book Roadways for People: Rethinking Transportation Planning and Engineering. We chat about better project scoping, capacity building, engineers going to actually walk and bike their project areas, and highway expansion in cities.

If you prefer to read instead of listen, check out an excerpt of the conversation below the audio player. If you want a full unedited transcript, click here.

Jeff Wood: There's a number of discussions in the book about centering people, especially in places like in Baltimore and in New Orleans, where, you know, the projects that you’re doing outreach and community input for aren’t moving along, but something happened in between that made the community trust that the process would be okay. With a place like 82nd Avenue in Portland, where the road was given back to the region by the state, there is a whole community of folks — the APANO folks, the Asian community there, the Jade District — that creates a discussion about how that road should be designed, how that road is used. I think that’s really fascinating, to think about those processes and how that focuses on people and not just a transportation project.

Lynn Peterson: Exactly. The planning process that was started on 82nd started with community members feeling safe enough, and we’ll get into what that means, to articulate what their needs were within that corridor, whether they were small business owners or whether they were kiddos getting to school. But 82nd Avenue in Portland is the highest transit ridership line in the entire region. There’s all these transfers that are going on east-to-west, north-to-south.

So just crossing the street as a transit user, or just needing trees to provide shade, were huge issues within the community. But if we started with the traffic engineer scoping out a project, they would say, well, all 10 of these intersections need new signalization. They need new hardware. There would be very little attention paid to the pedestrian crossing the street or the number of crossings per mile, right? So we started with the people to identify what they needed and then built out, with the traffic engineers and with the planners, like, how do we scope this project?

That’s where we usually get sideways. Somebody saw congestion at an intersection, they scoped the project, then it took 10 years to get to the planning process. By that time, somebody’s already estimated a cost for that project, and then they come and they say, "Hey, here’s the project we’re gonna do," and the community’s like, "That’s not the project we need. What are you talking about? We need X, Y, and Z."

The response is that giving the community what it needs would drive up the cost, so we’re not gonna be able to do that. Right? But it started 10 or 20 years ago, and that’s where I wanna focus. We need better scopes and better estimate ranges because we don’t know, right? We should never be held to something that was created 10, 20 years ago, but that’s what a transportation project takes to get through — between funding and the planning and the engineering, it takes 10 to 20 years.

We should never be set into a scope that was created 10, 20 years ago, so 82nd is a really good example. We started with the assumption that there was a lack of trust and that we had to build up trust.

We spent two years prior to being able to have that conversation on 82nd, actually building up capacity within community-based organizations to just be able to talk about transportation. We granted a lot of organizations — a lot of grants to be able to build up that capacity to hire staff and get get them up to speed with these projects.

In terms of APANO [the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon] and the Asian community, having folks that were trusted members of the community be able to go out and have those conversations in places that were safe and be able to speak in the languages that they felt they could actually communicate, and in not English — we got a lot more information from that kind of conversation, rather than just having a town hall meeting where an engineer gets up and says, "There’s congestion, here’s my solution, let me know what you think on this card," and then walks away.