In the first days of 2023, Lev Fruchter became an unexceptionally unlucky member of an already tragic club when his father, Norman, was killed by a driver while walking to his Brooklyn home — a horrifying crash that echoed the equally horrifying loss of Fruchter's mother, Rachel, who was killed by another driver 25 years earlier while biking just a few miles away.

In an additionally cruel twist, both of those drivers were enrolled in the New York Automobile Insurance Plan3, which serves dangerous motorists who technically haven't lost their licenses, but whose driving records are so bad that no private insurers are willing to pay the exorbitant cost of covering them. Under state law, though, those problem drivers can remain street-legal by entering what's known as an "assigned risk pool," after which they'll be assigned to an insurer who's legally required to write them a policy.

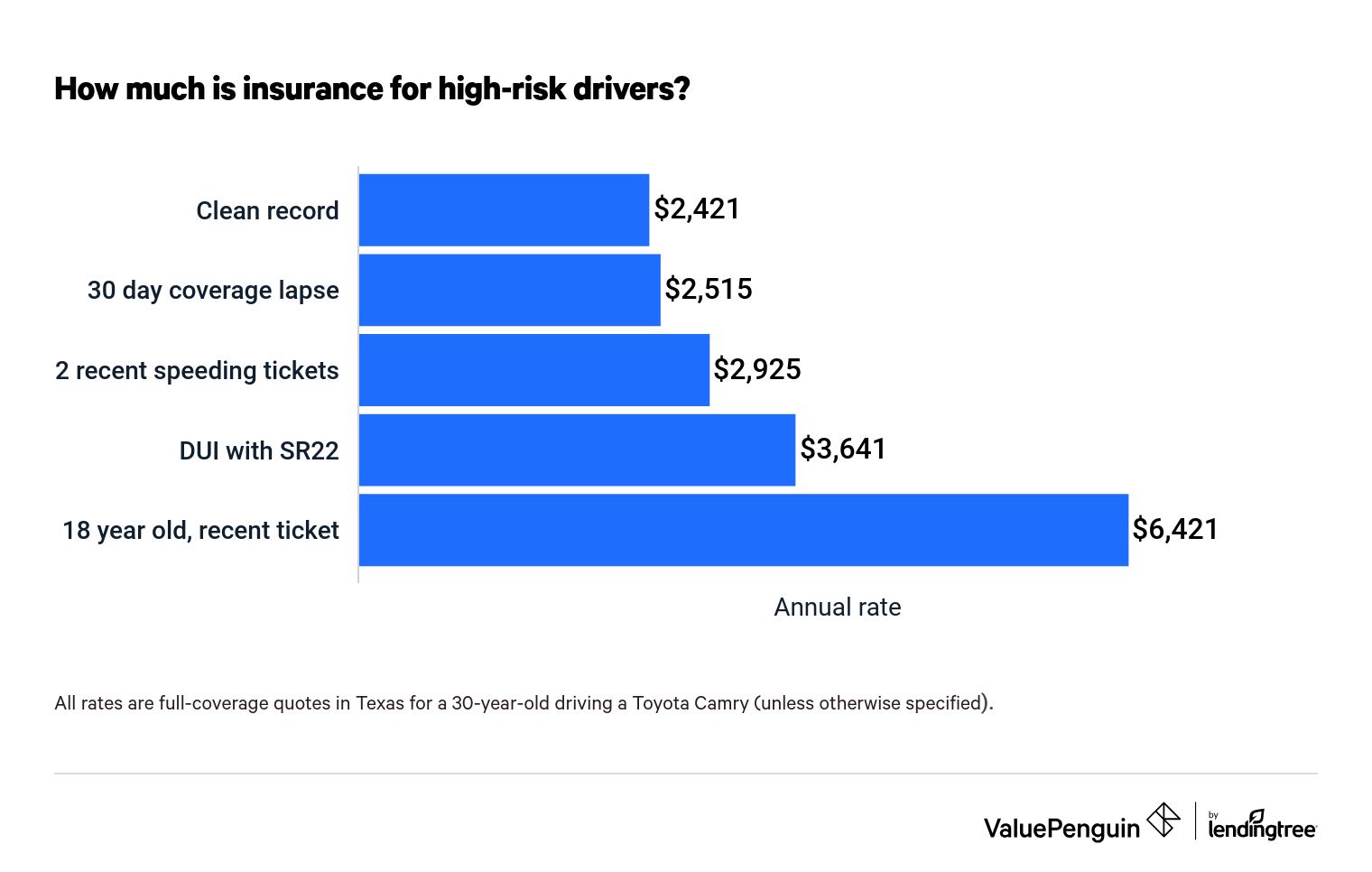

Those policies, of course, usually cost a lot more than ones on the private market. Some people, though, think problem drivers should pay with more than just their wallets when they persistently endanger other road users — and that perhaps they shouldn't be allowed on the road at all.

“God forbid that in this country we should take someone off the road for killing someone," Lev Fruchter told Streetsblog NYC earlier this year. “In this country, instead of saying, ‘Sorry, but your record is so bad, you don’t get to drive,’ they put you into a pool so you can get insurance so you can keep driving,”

At first, the Fruchter family's case may seem unusual; some estimate that less than 1 percent of New York State drivers participate in the pooled-risk program, and there's no data on how many families lose multiple members to crashes with motorists within that tiny group. The concept of an assigned risk pool, though, is far from rare; sometimes known as "residual markets" or "joint underwriting associations" — or, in the more-provocative words of personal injury attorney Steve Vaccaro, "Socialism for bad drivers" — they're common throughout the U.S., providing coverage not just to motorists with a history of roadway crimes, but to physicians with a history of malpractice violations, businesses with a history of worker's compensation claims, and many more.

Some people think that they essentially empower dangerous people to keep doing dangerous things on our roads, but other experts view the assigned risk pool as a necessary backstop to provide victims of problem drivers some measure of financial recourse — at least when drivers actually enroll in them, which they often don't.

"I've done over a thousand cases in this area, and I don't have a lot of experience with high-risk pools," said Peter Wilborn, a Florida-based attorney and founder of the Bike Law Network. "And the reason I don’t is because a lot of drivers who kill cyclists aren't in them, because they don’t have insurance at all."

Wilborn explains that rather than providing an incentive for drivers to behave more safely on the road, the threat of a steep insurance premium, or even ending up in an ultra-expensive high-risk pool, often simply incentivizes drivers to skip paying their premiums, period — especially if they're living in a car-dependent community and can't afford to move.

"If I wanted to avoid high insurance premiums, I might decide to live in a less car-dependent place," Wilborn adds. "But those places in the US are a product of affluence — which, by the way, is the opposite of how it works in the rest of the world. ... As much as I hate it, most people still have to drive [after they lose access to cheap insurance], and those people still have to balance their checkbooks and pay their bills."

That doesn't mean, though, that Wilborn has much sympathy for people who decide to forgo their legal obligation to hold insurance. He explains that of the motorists he sues, roughly 80 percent belong to a group he calls "scumbag drivers" who flagrantly disregard the safety of bicyclists and pedestrians, nevermind the financial security of their families when those road users are killed; a substantial portion of those crashes, he adds, are hit-and-runs, and a good chunk involve a motorist who was impaired by drugs or alcohol, or distracted by a cell phone behind the wheel.

Wilborn acknowledges that all three of those phenomena have systemic contributors that can be mitigated through good policy over time — think poverty, addiction, legally allowed infotainment systems that broadcast phones onto car dashboards, and even bad zoning that mandates parking outside bars — but he doesn't consider it his primary role as an attorney to address those factors. That's because he's focused on getting justice for victims who need help right now — not when structural change someday arrives. Many of his clients, he explains, are families who are not only grieving a loved one, but struggling with the sudden loss of a breadwinner they relied on to put food on the table; even crash victims who survive are often deprived of their ability to work, left addicted to opiates, or otherwise struggling with life-altering injuries and trauma.

"'Scumbag' is a loaded word; I get it," he adds. "But I’ve been to a lot of funerals, and scumbag is about the nicest word I can think of. ... Things like drug treatment can absolutely make roads safer, but that’s not the conversation we’re having today."

"Put simply, the roadway design standards enshrined by our nation’s professional civil engineers are unnecessarily deadly to the point of criminal negligence. It’s time to place blame and demand change." Via @JeffSpeckFAICP https://t.co/0SY7edEjwP

— The War on Cars (@TheWarOnCars) February 11, 2023

One way that attorneys can address the structural contributors to car crashes, of course, is to go after municipal insurance policies when they knowingly design dangerous roads — though Wilborn says those cases are hard to win. That's because many of the deadly streets in America comply perfectly with deadly design guidelines that either encourage our outright require transportation engineers to prioritize motorist's speed over other road users' safety.

Some advocates, like walkability expert Jeff Speck, have argued that the people who write and promote those guidelines should face "a massive class action lawsuit that properly lays bare the inner workings of this negligent industry." Until they do, though, lawsuits against cities who follow dangerous standards will likely continue to be rare.

"[Suing the designer of a dangerous road] is very complicated and it's really hard to do, but I’ve done it successfully," Wilborn adds, citing a recent case where a city replaced a pedestrian bridge over a multi-lane road with a "beautified" crosswalk adorned with poorly-maintained greenery that obscured walkers from the view of motorists. "I sue roads all the time, but it's usually about defects ... A 45 mile-per-hour street with multiple lanes built through a neighborhood isn't usually considered defective. We have a lot of those."

Until broader structural reforms are made, Wilborn says there is something vulnerable road users can do to protect themselves and their families financially in the event of a crash — even if their roads, unfortunately, don't protect them physically.

"I've been talking to bike groups for 25 years, and I always say, there’s only one thing I want you to remember: to call your insurance agent and get as much underinsured motorist coverage as they’ll give you," he says. "And if you can, get an umbrella policy [to supplement] that underinsured motorist coverage, too. That is how you take control over your own financial security when someone else hits you."