In most U.S. metros, renters and buyers alike pay a steep premium to live in walkable neighborhoods, a new report finds — except for a small handful of cities where they actually cost less than car-dominated ones.

Researchers at Smart Growth America painstakingly analyzed 35 major U.S. metros down to the census block group, in an effort to understand not just how theoretically easy it is for residents to get around without a car, but how much it actually costs to live and work in those walkable areas — and whether socially and racially marginalized communities are able to do it.

"It’s not just about walkability, because we also have to ask, how affordable is walkability?" said Michael Rodriguez, visiting director of research for Smart Growth America and a co-author of the new edition of the group's Foot Traffic Ahead report. "How accessible is it to transit? And how far away are [walkable neighborhoods] when you compare different social groups, like people of color vs. whites? Let’s say the average white person is one mile away from a walkable center, but the average person of color is four miles away; that’s definitely a negative."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the researchers found that Americans on the whole will pay significantly more for the privilege of living in a place where they can get around on their own power: specifically, 35 percent more for home buyers, 41 percent more for apartment renters, and 44 percent more for office properties.

Those stunning averages, though, were offset by a handful of cities where walkability generally costs less: the largely post-industrial cities of Baltimore, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, St. Louis, and Philadelphia.

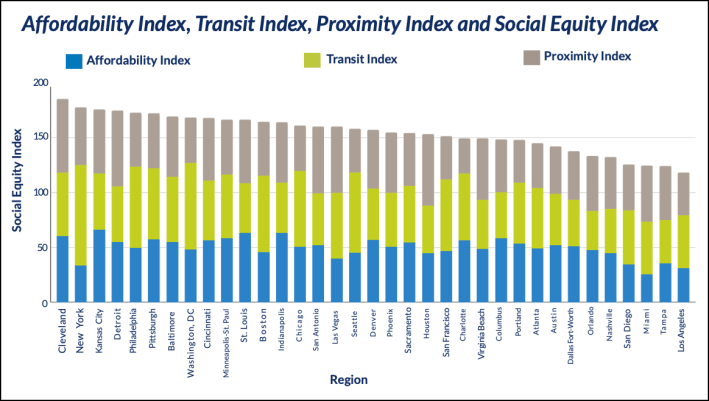

Moreover, in many of those metros, pedestrian-centered places are within usually easy reach of people of color, people with low income, and people with less educational attainment, among other privilege differentials. Cleveland, in particular, topped the report's "Social Equity Index" rankings; Baltimore, Cincy, Detroit and Philly also made the top 10, while St. Louis landed at number 11.

Some journalists, like Slate's Henry Grabar, dismissed the phenomenon as little more than "older cities [that have] have suffered from job loss and gun violence" over the decades, gradually devaluing their connected, pre-war neighborhoods that were once designed to make it easy for industrial-sector workers to reach their jobs on foot or by transit — at least until the streetcars were ripped out and downtown highways went in.

Rodriguez, though, says that the reality — and the history — can be more complicated on the ground.

"A pre-war grid surviving through the 20th century is actually a pretty impressive feat; it means you chose not to destroy it all," he said. "Cleveland was at one point the fourth largest city in the U.S., and if you look at old images and videos of it, it was vibrant as midtown Manhattan. These were proper cities, and we chose to enact policies that decimated that — but whatever we have left still provides a core of walkability today."

Rodriguez is also careful not to discount the efforts of mid-sized city leaders to keep walkability within reach specifically for less-privileged communities — or to discount what they're planning to do to increase access to people-centered places in the years to come. Cleveland's current mayor, for instance, has publicly announced an initiative to transform the Ohio community into a "15-minute city" where residents can access their daily needs without a car in a quarter of an hour or less, with a particular focus on vulnerable neighborhoods.

That will certainly be a challenge —an estimated 89.4 percent of Cleveland metro residents currently commute to work by car — but it may be within reach. Among the cities included in Smart Growth America's sample, Cleveland ranks as the 31st most walkable metro on Walkscore — a metric developed by real estate brokers that aggregates measures like the distance to neighborhood stables like grocery stores — but it ranks in 17th on SGA's own overall rankings, which incorporates a much wider array of data from the EPA, the American Enterprise Institute, and more. (For the first time this year, Walkscore was excluded from the rankings completely.)

If post-industrial cities like Cleveland can expand their inventory of walkable neighborhoods — and get the word out about the undervalued ones they've already got — Rodriguez is optimistic that they can attract new residents.

"There've been a lot of articles lately that say something like, 'hey, you want to live someplace walkable? Try this non-top-ten city,'" Rodriguez adds. "This confirms [that impulse]; there are good deals to be had in places like Cleveland. Maybe you can't afford to live in New York City, but you can afford to live in, say, the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood in Cincinnati, or maybe Carmel, Indiana outside of Indianapolis."

Rodriguez is careful to underscore that what constitutes "equitable" access to walkable places can be complex and context-specific. Perhaps shockingly, notoriously expensive New York City actually ranked second on the Social Equity Index, which he attributes to its proportionally high median incomes, astounding diversity, and the sheer preponderance of transit and people-oriented places that make car-free living possible for virtually everyone; residents of Manhattan, after all, spend an average of 37 percent of their income on housing and transportation combined, while residents of car-oriented Indianapolis spend 42, according to the Housing and Transportation Index.

In truly equitable country, though, (relatively) equitable access to walkable neighborhoods wouldn't be a rare commodity concentrated in megacities with a lot of wealthy residents; they'd be a naturally-occurring part of every city and town. And they still could be, if communities did more to implement zoning reforms, foster non-automotive travel, and invest in affordable housing for all.

"We’re not saying you need to kill the suburbs or abolish single family homes," Rodriguez adds. "One of the most equitable things we could do would be to just add more walkability in the US. The reason walkability isn’t more available to more of us is because just 1.2 percent of this country is walkable right now. If you even so much as doubled that, you’d meet a lot of the demand."