America's top regulatory agency is failing its mandate to “keep people safe on America’s roadways” — and to truly accomplish it, it needs to fundamentally change the way it operates, a new paper argues.

In a fiery recent article in the New York University Law Review, University of Iowa professor Gregory Shill argued that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has so aggressively prioritized the safety of drivers over other road users that today, the agency effectively "considers the safety of pedestrians — who are third parties rather than consumers — almost completely alien to its mission."

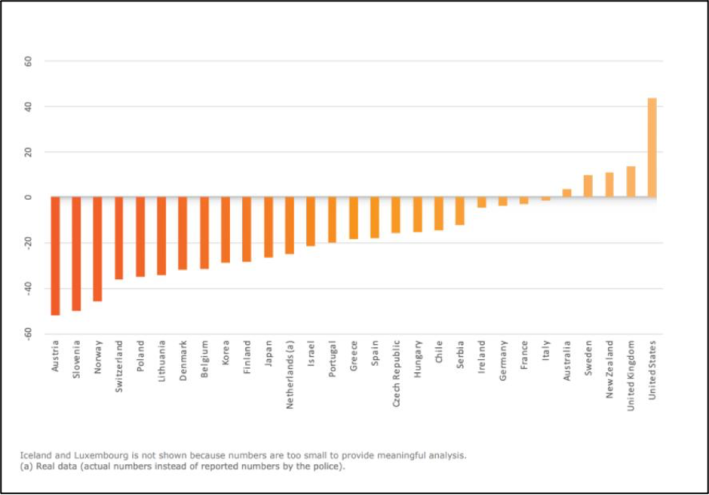

That consumer-protectionist attitude, Shill says, has directly enabled automakers to flood U.S. roads with SUVs and pick-up trucks despite how dangerous those cars have proven to be for people on foot. As pedestrian deaths declined in nearly every industrialized nation on Earth during the 2010s, U.S. fatality totals soared more than 46 percent — a burden that falls disproportionately on Black road users, who today face an additional 66-percent risk of being killed while walking than their white counterparts.

Nonetheless, the same cars that helped cause those numbers to skyrocket almost universally achieved five-star safety ratings from NHTSA's New Car Assessment Program — because unlike other countries, that program doesn't take into account the safety of people those vehicles might strike.

NHTSA's narrow interpretation of the term "public safety" isn't just an anomaly globally. It's also anomalous among federal agencies — and Shill says there are better models within Washington right now.

"Imagine if the Federal Aviation Administration only regulated airplanes for the benefit of people inside airplanes," Shill added in an interview with Streetsblog. "What if that meant that airplanes routinely dumped jet fuel or other debris on people’s homes, or on playgrounds? That kind of thing is not allowed, despite the fact that the people who are harmed by it are not consumers of airline services. That's the goal that NHTSA is supposed to be pursuing."

Here are four recommendations that Shill says regulators should adopt right now to help them achieve it.

Make it clear that protecting pedestrians is a part of 'public' safety

Perhaps the simplest thing that NHTSA can do to "keep people safe" on U.S. roads is to clarify what they mean by "people" — and make it explicit that pedestrians are included.

Shill argues that since the Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 first defined the term as "measures that protect ... the public against unreasonable risk,” the agency has had a legal obligation to protect all members of the public, including those who aren't inside a car. Simply by using the vague phrase "the public" rather than specifying who that umbrella term includes, though, NHTSA has avoided meaningful pushback, even as it's become increasingly clear that regulatory inaction on automakers is a major contributor to the national pedestrian death surge.

"By definition ... pedestrians cannot benefit from vehicle traffic," Shill writes. "It would be perverse to argue that they benefit from measures that are designed to safeguard only vehicle occupants: Not only are those measures not undertaken for their benefit, but there is some evidence that they increase harm to pedestrians."

By making explicit in their mandate that "public safety" includes pedestrian safety, perhaps lawmakers and advocates could more easily hold NHTSA accountable when they give glowing safety ratings to SUVs that protect their occupants at the direct expense of the people they strike.

Make cars safer for walkers — starting with their size

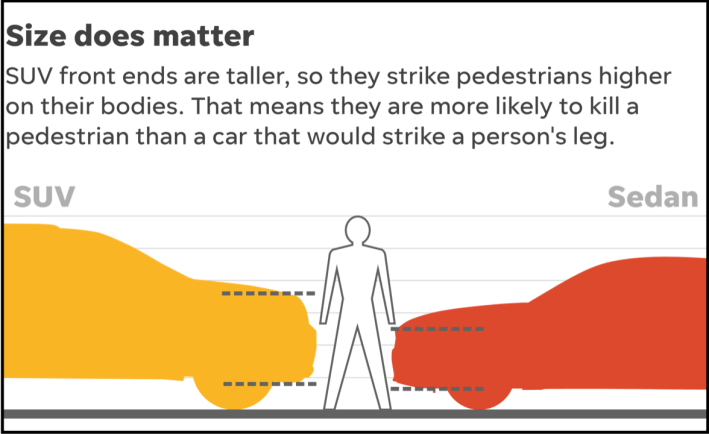

Resolving to save pedestrian lives, of course, is different than actually doing it. That's why the obvious next step NHTSA must take, Shill says, is to revise motor vehicle safety standards and federal consumer safety ratings to account for how likely a given car is to kill a person on foot — a calculation which usually starts with simply how big and heavy they are, as well as the design of its front end.

"There isn’t a safe speed for a vehicle that weighs thousands of pounds to strike a human being, but there’s lots of things you can do to make it less deadly," he added. "A smaller car that is lower down may not need the same pedestrian protections as a 9,000-pound electric Hummer. It may not need the latest technology; it could mean a bumper that crumples on impact, as much of our peer nations [already require]."

Unfortunately, a recent proposed rulemaking issued by NHTSA included only a brief hint that the agency might soon give cars with walker-safe "hood and bumper designs" a higher safety grade under the New Car Assessment Program — and didn't explicitly say that heavy, tall, cars would get a lower score. If the agency took that step, Shill is hopeful that at least some consumers would prioritize the safety of their neighbors when they go to the dealership, even if megacars weren't explicitly banned under Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards.

"Right now, this is not a problem that people are widely aware of," Shill said. "Even if my whole suite of programs isn’t adopted, simple disclosure would make a big difference."

Support high-tech solutions, but scrutinize them

The agency has so far declined to regulate vehicle size outright, but NHTSA's proposed pedestrian safety rulemaking would include a suite of high-tech solutions to save vulnerable lives on our roads, including pedestrian automatic emergency braking, blind spot detections, and possibly even speed-limiting technology which became the law of the land in Europe a year ago.

Shill points out, though, that a lot of that tech is still pretty nascent, and we should really make sure it's road-ready before we rely on it to save lives. And that means thinking beyond the crash tests we use now, which are conducted in controlled environments in full daylight, but in the kind of roadway environments where pedestrians are disproportionately killed, like dark roads with no street lights.

"Rulemaking on the basis of tests conducted in controlled settings is not sufficient," Shill wrote. "Instead, NHTSA should take account of real-world conditions in corridors and circumstances that generate a disproportionate share of pedestrian deaths."

Make crash tests truly inclusive

Even on cars without the latest automated driving tech, though, Shill argues that U.S. crash tests often fall short — especially when it comes to protecting people who don't fit the typical crash test dummy mold.

That's because simply scaling a mannequin to the average height of the "typical" man, woman, or child doesn't account for the many internal differences between a diverse range of bodies of all ages, genders, abilities, and sizes, not to mention the different ways those groups tend to move in the roadway environment.

A "biofidelic" dummy in a more thoughtfully designed crash test, for instance, would account for the fact that seniors tend to move more slowly, have different bone density, and often live with a range of age-related health conditions that younger road users don't. Put it all together, and people over 65 years old are 35-percent more likely to be killed than the general population when struck by a driver, or up to 75 percent for older male who use wheelchairs — though NHTSA's crash tests don't reflect those horrifying disparities.

Those differences are even more pronounced when it comes to children, whose unique psychology Shill says is largely unaccounted for in modern crash tests, even as traffic violence remains the number one killer of kids under 12. In many cases, those children are pedestrians when they're killed.

"It’s not just that kids are short and parents can’t necessarily see them," he adds. "It’s that an adult would know not to stand behind a car that’s backing up, but a child might not — or they might not react in the same way [when that happens]. The way to prevent those deaths is not just about education; it’s to acknowledge the limits of education, and acknowledge that kids are going to run in front of cars sometimes, because they don’t have the self-regulation yet to recognize that’s dangerous."

Shill points out that updating its crash tests — just like adopting his other three recommendations — wouldn't shift NHTSA's day-to-day work all that much. And considering the staggering financial costs of car crashes, it may even save the government money in the long run.

"Though widening the aperture in this way would increase the number and nature of beneficiaries of vehicle safety regulation, it would not require major changes to the actual work that NHTSA does or the expertise it uses to carry it out," he wrote. "The agency has the capacity to leverage the best evidence and technology to safeguard pedestrians, and should use it."