An 11th-hour legal battle over the future of one of America's most talked-about highway teardowns is sparking a debate about what it really means to "reconnect communities" that were devastated by federal infrastructure investments — and it may offer a preview of similar fights on deck in other U.S. cities.

Environmental justice advocates in Syracuse were stunned last month when the state Supreme Court (which, despite the name, is not New York's highest court) ordered transportation officials to pause work on the I-81 viaduct project, which would replace an aging stretch of elevated highway near the city's downtown with a human-scaled street grid.

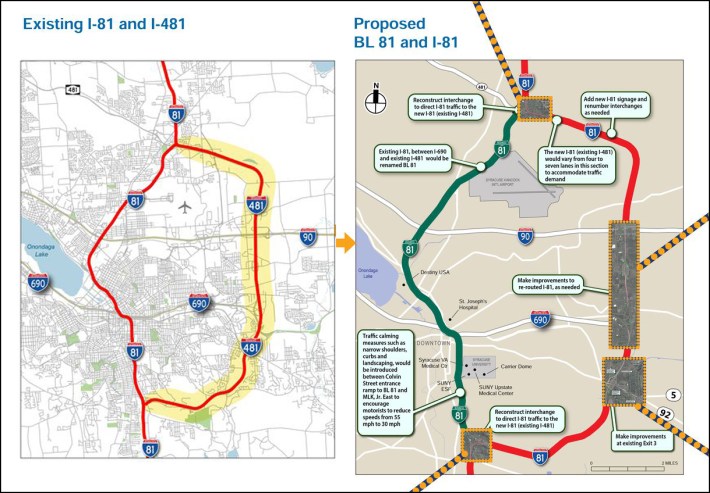

Nearly 14 years in the making — including nine years of environmental review — the proposed teardown had been celebrated by the likes of White House Infrastructure Czar Mitch Landrieu, who urged Mayor Ben Walsh in October to "very strongly and very aggressively ... become the model for the country" as other communities embark on similar projects. Under the newly established Reconnecting Communities as well as the Neighborhood Access and Equity programs, U.S. DOT is poised to funnel billions of dollars to help cities stitch together neighborhoods torn apart by the interstate highway system, particularly in the BIPOC and low-income areas that were overwhelmingly targeted for demolition.

In Syracuse, though, some residents of those communities are among the plaintiffs in a lawsuit seeking to halt the viaduct teardown, in hopes of replacing it with an even bigger highway — while others are among the loudest voices in the fight to bring the project back to life.

And national advocates think that other cities should anticipate similarly thorny conversations.

"It speaks to how complicated the issue of converting a highway is for all the parties involved," said Ben Crowther, advocacy manager for America Walks and one of the creators of the Freeway Fighters Network. "And it also speaks to a certain level of distrust that’s come about because of agencies like New York State DOT’s historic role in building highways, too."

'Constant roaring'

Despite their very different visions for its future, nearly everyone in Syracuse seems to agree that the history of I-81 is a disgrace.

Before the viaduct was plunged into its very heart, the 15th Ward was the epicenter of Black life in Syracuse — at one point, almost 90 percent of the city's African-American residents lived there — as well as a major haven for Jewish and immigrant populations in upstate New York. A staggering 1,300 of those families were forcibly displaced when highway construction began in the 1960s, ripping a hole in a tight-knit working class community which Syracuse University history professor Otey Scruggs once described as a place where "camaraderie ... blossomed from [everyone] knowing virtually everyone."

That sense of community was so strong that many Black Syracusians still refer to their neighborhood as the 15th Ward today, even as the landscape around them has transformed. Today, the communities west of the highway are still overwhelmingly Black, but the blocks to the east have grown wealthier and whiter, with large swaths devoted to university and hospital campuses. For people outside cars, destinations on the opposite side of the highway can only be accessed by crossing under the crumbling viaduct, which leaks so much when it rains that it's difficult to cross without getting drenched in highway runoff.

"You actually cannot physically see over the highway [from the neighborhoods to the west]," said Lanessa Owens-Chaplin, director of Environmental Justice for the New York Civil Liberties Union. "As a kid, if you’re living in a community that has little to no opportunity, but you know it's right across the highway — that does something to you."

Owens-Chaplin, who is Black and who grew up in the shadow of I-81 herself, says that the racist impacts of the viaduct are more than symbolic. Studies from the NYCLU have found that the region is a hot spot for asthma, heart disease, and lead poisoning, thanks in part to the constant onslaught of gasoline fumes pouring down from the viaduct. She and her colleagues have has spent years going door to door amassing comments from those impacted most, some of whom live less than 500 feet from speeding traffic.

"We heard stories about people having to clean the outside of their windows all the time because of the soot," she added. "We heard about how scared they were with their kids playing right next to a major highway; we heard about how ugly they think it makes their community. They talked about living with the constant roaring [of cars]."

Urban renewal, Black removal

Some residents, though, fear the removal of I-81 may result in their own.

One of them is Onondaga County Legislator Charles Garland. While he represents one of the majority-Black districts that would be most directly impacted by the teardown, he's also a third-generation director of a local funeral home whose original building was torn down to make way for I-81. He's concerned that painful history will repeat itself once the viaduct is gone and gentrification sets in.

"They say it’s this utopian thing, where professors are going to be living alongside people on public assistance," adds Garland, who is also Black. "That sounds like a great thing, but it’s not going to happen."

Some of Garland's concerns stem not just from the viaduct project itself, but from an interwoven effort to reimagine public housing in the highway's wake.

Local officials hope to capitalize upon the teardown (and the grant funds attached to it) to embark upon an $800-million initiative to raze hundreds of aging housing projects built in the highway's shadow, and replace them with a mix of affordable and market-rate homes. Proponents of the plan say the effort will bring new opportunities to a neighborhood that's been locked into poverty for nearly 80 years, and that residents will be given the choice of another public housing unit in Syracuse, or a housing voucher that will allow them to move anywhere in the country.

Garland isn't buying it. He believes that the teardown will enable an historic land grab among the "eds and meds" institutions whose growth is physically constrained by the existing highway, and points out that both employers are already actively encouraging their disproportionately White employees to settle in the area.

And he claims that many locals share his concerns: in a survey he commissioned, just 18 percent of residents of the area near the highway said they supported its removal, compared to 39 percent who favored repairing it. Notably, though, that survey only included 138 people, compared to the more than 5,000 comments in support of the teardown that the NYCLU says it has collected so far.

In the suit that's brought the I-81 project to a pause, Garland and his co-plaintiffs in the Renew 81 for All coalition said that NYS DOT had violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act by failing to adequately consider the detrimental impacts of the project on racial minorities — the same legal argument, ironically, that's gotten highway expansions paused in other cities like Houston.

"Why does urban renewal always mean Black removal?" Garland wondered. "Why do people have to move from the communities they live in to go to better areas, rather than making the neighborhoods where they live right now better? ... When they come into our community, they say what they think we want to hear. But that’s not what they say to everyone else."

The 'Freedom Bridge'

Many supporters of the highway teardown agree with Renew 81 For All on one point, at least: that local leaders aren't doing enough to ensure that today's residents will have a guaranteed place in the 15th Ward once the grid is restored.

Owens-Chaplin emphasizes that the city must do more to "build a plan that goes above and beyond the federal requirements" to protect vulnerable communities, both by offering significant relocation assistance for those at particular risk of exposure to harmful pollutants during the construction phase, and by creating a community land trust for their benefit after the viaduct comes down.

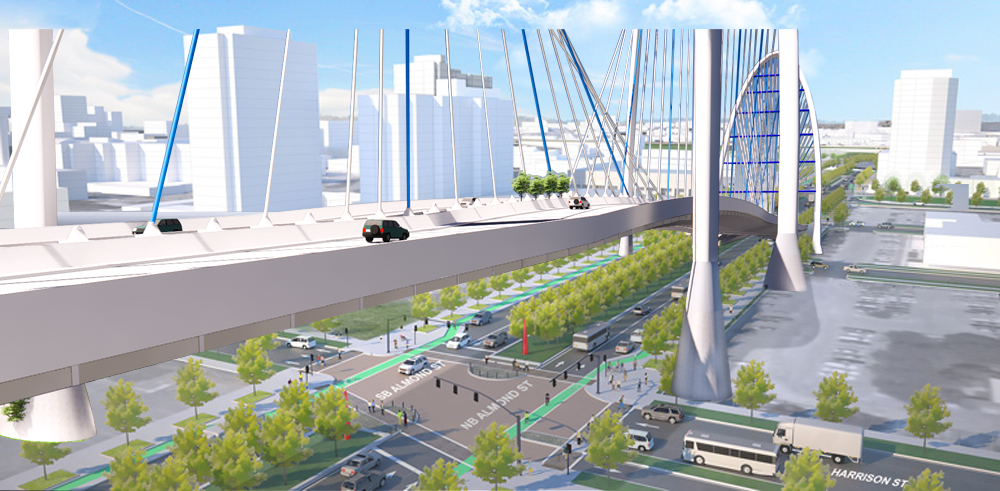

Some of Renew 81 For All's other arguments, though, are raising more eyebrows — and so is their counterproposal to replace the viaduct with a mammoth, seven-story tall "skybridge" instead.

Garland and his co-plaintiffs argue that the skybridge — which supporters prefer, controversially, to call the Harriet Tubman Memorial Freedom Bridge — would create space for a more meaningfully connected network of streets at ground level by eliminating all city exits, while still allowing through-traffic to bypass Syracuse's downtown from a lofty height of 68 feet.

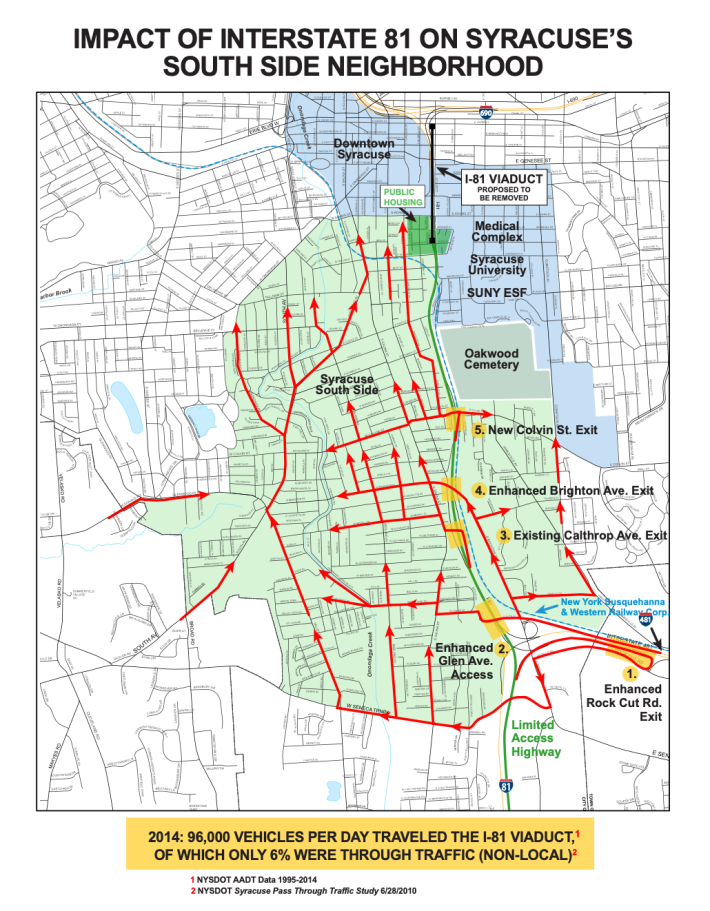

The coalition also claims the skybridge is a more equitable alternative to simply tearing down the viaduct, particularly for the descendants of BIPOC families who were forced out of the 15th Ward when it was built in the first place. Because of the way I-81's downtown exits would be sited if the viaduct came down, Garland says the predominantly Black neighborhoods on Syracuse's south side that absorbed many of those ousted residents would be suddenly flooded with ground-level car traffic and all the congestion, traffic violence, and pollution that comes with it.

"That’s always been the formula; remove us from where we live, gentrify the area, then redirect the problems back into the communities [where we were relocated]," Garland said.

Transportation experts generally say, though, that highway teardowns virtually don't result in a ground-level carpocalypse, because motorists seek alternative routes that allow them to avoid the inconveniences of downtown traffic — or they find other ways to make their shortest journeys on modes other driving. While the New York State DOT anticipates that roughly 40,000 cars a day would flow through Black neighborhoods on the south side under the community grid plan, Owens-Chaplin emphasizes that's actually 60 percent less than the 100,000 cars that travel the viaduct now, which would translate to immediate health benefits for area residents.

She also says there is no evidence that the Tubman bridge plan would mitigate air pollution as its proponents claim it will — though it might have benefits for suburbanites and automotive interests.

In addition to BIPOC leaders like Garland, the group behind the lawsuit also includes the New York State Motor Truck Association and the overwhelmingly White towns of Dewitt and Salina to the city's east. And she suspects they may be less concerned with preventing ground-level traffic in Black neighborhoods than creating an even faster route to bypass communities of color.

"The cars that will be coming to the community [after the viaduct comes down] will [still] be coming to the community – to drop their kids off at school, to go to work, to go to to parks," Owens-Chaplin added. "I can’t be more frank; [supporters of the skybridge just] don’t want to drive through a Black neighborhood. They’re benefiting from historically racist practices, and they want to continue to benefit from historically racist practices."

Opponents of the teardown, though, see it another way — especially when viewed in the larger context of the project. Even as they remove the segment of I-81 downtown, NYS DOT actually plans to expand several segments of I-481 just outside the city's borders, which the agency (dubiously) argues is necessary to replace lost capacity, and which it says won't cause significant harm to the less-populated suburban regions to the city's east. Still, that could muddy the project's progressive image among sustainable transportation advocates who think America already has more than enough lanes.

"To some of us, [the viaduct teardown] looks like a way of simply spending a bunch of money to expand the interstate to enable more quick access out in the suburbs, at the expense of not only the taxpayers, but also the minority communities of Syracuse," said Dennis Grzezinski, a lawyer for Renew 81 For All coalition (and, notably, someone with a long reputation for opposing freeway expansions in other states). "Instead of this being a glowing example of a great [racial justice] project, this might be the rotten apple that might spoil the whole bushel."

'The speed of trust'

For now, the future of the I-81 project remains uncertain.

Garland and his co-plaintiffs quickly doubled down on their success at the State Supreme Court with a federal lawsuit, and remain hopeful they can ultimately convince NYS DOT to re-examine the Harriet Tubman bridge option. Owens-Chaplin is still confident that won't happen, and the viaduct teardown will continue as planned; she says these types of lawsuits are common, and her group is hopeful that a recent amicus brief they filed in support of the project will help sway the judge.

How long that might take, though, is still an unanswered question. And as communities across America consider the future of their own Reconnecting Communities projects, advocates are warning them to buckle up for a long haul — and prepare themselves for difficult conversations.

"At the end of the day, these projects should arise from a grassroots level, and the vision for what to do along a highway corridor needs to be informed by residents who are living there now," added Crowther. "There's no simple answer [for what that looks like], but the simplest answer might be that these projects need to move at the speed of trust ... Other communities that are thinking about undertaking Reconnecting Communities projects should learn some lessons here from what’s going on in Syracuse, and expect these sorts of challenges. It shouldn't take us by surprise."