Driver aggression is far from the only reason why people don't ride bikes, a new report finds — and if they paid more attention, policymakers could seize the opportunity to systemically address the most frequently ignored "personal" barriers to traveling on two wheels.

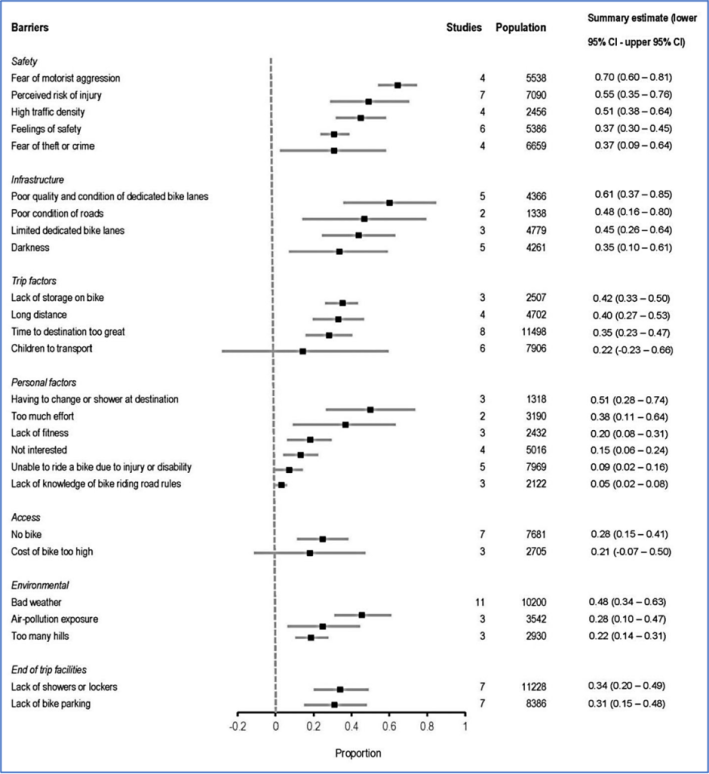

In perhaps the most comprehensive literature review on the topic to date, researchers at Monash University in Australia analyzed thousands of international studies of why people ride — or don't — and sifted it down to 45 essential papers. Unsurprisingly, "fear of motorist aggression" ranked at the top of the list of barriers for most riders, closely followed by "poor quality and condition of dedicated bike lanes" — including bike lanes whose "condition" was little more than a line of paint on the ground sprinkled with broken glass.

But beyond those obvious roadblocks lay a universe of under-studied factors shaping the ways that road users get around — many of which have important implications for policymakers, nonprofit partners, and even the bike industry.

The researchers found evidence, for instance, that some people don't ride because they simply weren't taught the rules of the road for people on bikes the same way many are for drivers — and may fear that knowledge gap could leave them in danger of either a crash or harassment by police, particularly for BIPOC.

Others knew about local bike laws, but found specific policies, like mandatory helmet requirements, so onerous that they'd be unlikely to ride unless those rules were struck down. And some reported that they were dissuaded by hilly routes — a barrier that could at least partly be surmounted by putting protected routes on flatter terrain when possible, and increasing public subsidies for hill-crushing e-bikes.

Those were just three of the 34 barriers and 12 enablers that the researchers included in their final ranking, but they say they wish they could have covered more.

"There were a lot of things we couldn’t include, because articles have word limits and there was just so much data," said Lauren Pearson, the lead author of the study. "And it varies a lot from group to group. Women, for instance, report that having to ride on the road is a much steeper barrier [than it is for people of other genders], and that's in part because they face less harassment from people inside passing motor vehicles; women with children, though, have different motivations for wanting the same thing. ... These wide-scale infrastructure measures can make the largest difference for the largest number of people, but how we implement them will impact different people in different ways."

Here are three overlooked, individual reasons people don't ride — and what we can do about them systemically.

1. Bikes not built for daily life

Buy a car at a U.S. auto dealership, and it's pretty likely it will come with a trunk, a lockable door, and a set of working headlights at no extra charge. Buy a bike at a U.S. shop, though, and basic storage, security, and illumination almost always cost more — and it may be putting people off pedaling completely.

Fear of bike theft, lack of on-bike storage, and fear of riding in darkness all ranked among the common reasons why people don't ride — and the need to transport children ranked especially highly, with 15 studies name-checking it as a significant barrier.

All those problems could be addressed, at least in part, by developing the market for all-inclusive, do-anything bikes with all the "accessories" — or more accurately, basics — integrated directly into the design, not to mention bringing down the cost of e-cargo bikes capable of carrying kids.

Considering how much money the federal government has poured into developing automotive technologies and bringing down the cost of automobile ownership over the years, maybe it's not so far-fetched to imagine that it might one day invest in creating a bike industry where something as simple as a fender to protect a rider from puddle splash-back isn't almost universally sold as a luxury add-on.

2. Bad weather, bad clothing

Policymakers can't control the weather — but they could help would-be bicyclists navigate the challenge of biking in even the worst conditions.

The Monash researchers found that the most common barrier to biking was bad weather, but respondents might be encouraged to ride by, for instance, mandating that developers in hot cities build showers at new workplaces, like the Ontario city of Kingston did in select locations last year. Snowy conditions, of course, are often synonymous with snow-clogged bike lanes and treacherous ice on the roads, but both can be mitigated with strong commitments to maintain cycling infrastructure in all four seasons, as cities like Holland, Mich. already do.

the lycra discourse happens every three months and it’s very silly each time

— hopeful and positive leftist (@emilymhorsman) September 28, 2022

- wear whatever you want to bike, you don’t need any particular clothes to do any particular riding

- being prescriptive in either direction is needless gatekeeping tied to different cultures of riding+

Governments don't usually get involved in helping commuters buy the right clothes to cycle comfortably in uncomfortable conditions, but the Monash study suggests that maybe they should consider it. (The cost of certain types of work apparel, after all, is already eligible for tax deductions, though usually not the clothes worn to get to work, never mind anywhere else.) Not owning "suitable clothing" for cycling was cited as a common barrier in four separate studies in the researchers' sample — and while few people really need a set of padded Lycra shorts or a bike-specific windbreaker to ride, a lot of people think they do, and some even skip riding completely when they don't have special gear. Policymakers and bike-supporting nonprofits should probably take note.

3. Negative perceptions of cyclists

Perhaps the trickiest biking barrier isn't on the road at all, but inside would-be riders' minds.

The researchers found that five studies cited "negative community perception of cyclists" among the reasons their respondents didn't bike — which study author Pearson says is, in part, a problem of public messaging.

"When people talk about 'cyclists,' there’s this quite negative community perception of that word," she added. "There’s been some really fantastic work done around imagery and wording that's found that the term 'cyclist' portrays an image of this strong, fearless, risk-averse person that people don't always relate to. But at the same time, studies show a lot of those people are thinking, 'Hey, I really love riding my bike; that word just doesn't describe me.'"

As policymakers work to physically elevate the status of people on bikes by putting them on separated paths above the grade of the road, the Monash study suggests they can elevate them socially, too, through smart public awareness campaigns that skip the "c" word and make it clear that cycling biking can truly be for everyone.