As Americans await transit projects that take decades to build, we should use the Biden Administration's infrastructure law to speed up a forgotten transit project that could move hundreds of thousands of riders daily.

Growing up in New York City I was well aware of the Second Avenue Subway and the many stops and starts that have slowed that project, yet I never knew that there was a city that had been waiting even longer for their subway. Next year marks 110 years since the Roosevelt Boulevard Subway was first proposed in 1913, and some wonder if it could be built with Bipartisan Infrastructure Law money.

Do we need it? Yes!

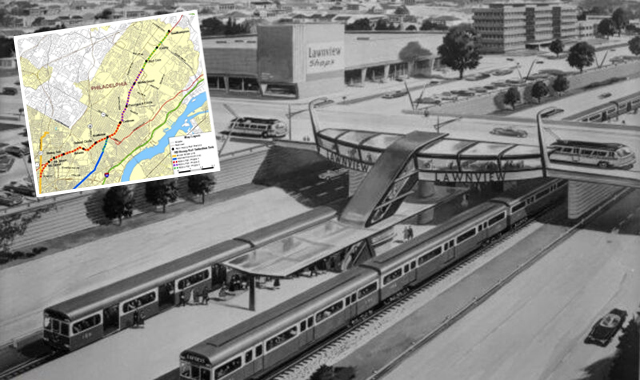

Roosevelt Boulevard is the tree-lined spine of Northeast Philadelphia that travels 14 miles through a mix of immigrant communities, dated shopping malls, and industrial businesses. It's also an exceptionally dangerous roadway. Unlike the rest of Philadelphia, some neighborhoods adjacent to Roosevelt are auto-centric, creating deadly walking conditions and poor transit options. Still, because of the population density in communities adjacent to Roosevelt Boulevard, a subway line has been proposed numerous times in the last century.

It was first proposed in 1913 by then-Director of City Transit A. Merritt Taylor. Taylor's plan for Philadelphia's Rapid Transit would have substantially boosted the development of Philadelphia's high-speed subway system. The 1913 plan called for the immediate construction of subway and elevated lines that would have made Philadelphia's system akin to Chicago, Boston and New York City's subway systems. One of the numerous lines mentioned in Taylor's plan was an elevated subway line up Roosevelt Boulevard.

The new line would have connected Northeast Philadelphia to the rest of the city and pushed for the development of the then-sparsely-populated area.

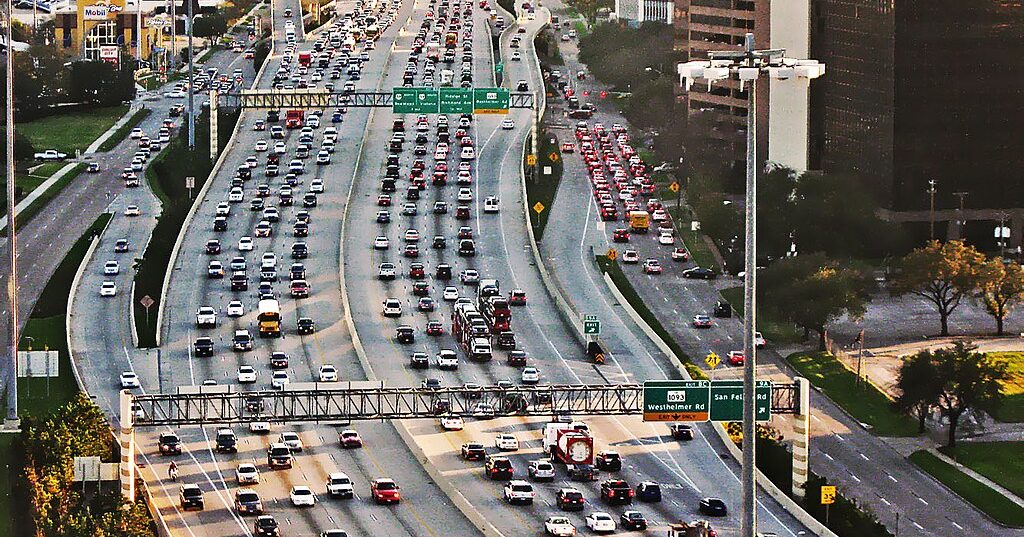

Out of the many lines proposed in Taylor's plan, only the Broad Street Subway and Market-Frankford Lines were built, leaving Northeast Philadelphia without subway service. Instead of becoming walkable like the rest of the city, segments of Northeast Philadelphia were built for improved car access. This trend increased in 1961 when the south end of Roosevelt Boulevard was connected to the Schuylkill Expressway (I-76) via the 3.5-mile Roosevelt Expressway; this led to a massive influx of new shopping malls, suburban-style homes and white flight to Northeast Philadelphia.

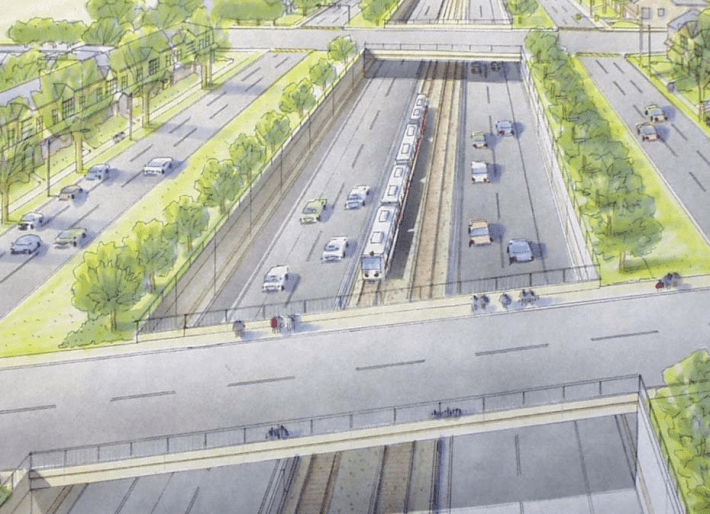

For some residents of the area, the idea of a subway on Roosevelt Boulevard was not attractive; they came to Northeast Philadelphia to escape urban life and get a piece of suburbia. A subway threatened to give access to the public, which residents believed would increase density and decrease home values. In 1960, the City of Philadelphia released its first Comprehensive Plan that proposed tracks for a new subway line in the center median of the proposed Northeast Expressway. Roosevelt Boulevard would have been largely destroyed in this planned expressway.

The 14.9 mile-long highway was estimated to cost $94 million. The subway line would cost an additional $94 million to construct. It almost looked like the subway would be built in the 1970s. Unfortunately, the project was dealt a lasting setback in 1977 when PennDOT halted funding for all unbuilt highways, killing both the expressway and subway. This was primarily due to Northeast Philadelphia residents opposing the destruction of Roosevelt Boulevard.

Over the next few decades, the demographics of Northeast Philadelphia started to change as Chinese, Vietnamese, Albanian and Latino immigrants moved in, many of them transit dependent. In the late 1990s, residents of Northeast Philadelphia, concerned about their quality of life and the livability of their neighborhoods, called for more significant transportation improvements for the Northeast.

Recent efforts

After decades of suburbanization, Northeast Philly was ready to head in a new direction. In response to these issues, the Roosevelt Boulevard Study was released in 2003. The study looked at Bus Rapid Transit, Light Rail, Enhanced Bus, and Heavy Rail alternatives for the corridor. The study's preferred alternative was a new modern subway/elevated line along Roosevelt Boulevard that would connect directly to the Broad Street Line's express tracks for rapid travel to Center City; it would have cost between $2.5 and $3.4 billion in 2000 dollars.

Ridership forecasts showed that a Roosevelt Boulevard subway line was the strongest nationwide. The line would have had a daily ridership of 124,500, taken 83,300 cars off the road, and produced over 12,929 hours in travel-time savings. Ultimately, the City of Philadelphia struggled to find funding for the subway alternative.

The region searched for a more affordable transportation option. In 2017, an enhanced bus route called the Boulevard Direct, serving Roosevelt Boulevard between Frankford Transportation Center and the Neshaminy Mall was launched in the fall of 2017. This new bus route provides frequent service with fewer stops but doesn't have any exclusive lanes or signal priority. The enhanced bus has not spurred transit-oriented development adjacent to its bus stops.

Next year marks the 110th anniversary of the proposed Roosevelt Boulevard Subway, and there is a renewed push to study the corridor again. Altogether, President Biden's Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the Federal Transit Administration's RAISE discretionary grants, and New Starts funding might make funding the subway line within the realm of possibility. Any federal grants would require a local match from PennDOT and the City of Philadelphia which could be a potential challenge for a region with many transportation needs. I hope that the legacy of this project, the 124,500 daily riders and the economic development potential can be reasons why this project would be able to obtain federal funding and other discretionary grants.

The Roosevelt Boulevard Subway is a significant infrastructure project — and it should be the kind of project that the Biden administration should fund: a transportation project that could better connect a disjointed region, reduce vehicle miles traveled and create thousands of jobs in a critical swing state. The federal government has considerably increased federal funding available for capital projects; however, most of that funding in southeastern Pennsylvania will go to repair/rebuild projects rather than rail system expansions.

So after nearly 110 years, Philadelphians are still waiting for the Roosevelt Boulevard subway, and in the near future, a train might come; but in the meantime, we are asking for President Biden to get the ball rolling so we can get Philadelphia moving. Build the Roosevelt Boulevard Subway.

Jay Arzu is a Ph.D. student in City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design and is the co-founder of the Collective Form, a walkable urbanism and community engagement platform. Connect with Arzu on LinkedIn.