Imagine you're out walking on a shared-use path in your city, and these vehicles blast through your periphery at 30 miles per hour. They have two wheels, quiet electric motors, and the people atop them are pedaling, though clearly, the battery is doing almost all of the work.

And they're going a little too fast for your comfort (hell, their riders are even wearing Daft Punk-style motorcycle helmets!). It's called a HyperScrambler 2 from Juiced Bikes. And in many jurisdictions, the pedals make it completely legal. So...

Now imagine you're on that same path, but then one of these things — a Delfast Top 3.0i — speeds by at 50 miles per hour, narrowly avoiding a parent with a stroller. Pedals, check; battery, check. But otherwise, that sucker sure seems like a motorcycle.

Now imagine this beast comes up on you from behind. Its riders max out at just 18 miles an hour — slower than some of the spandex-clad cyclists on manually-powered bikes, sure, and exactly the same speed as your city's shared e-scooters. Those vehicles, though, both weigh a whole lot less than than this 400 pound monster trike, and it's way too wide for the path, which means it could probably do some serious damage to a pedestrian in a crash.

Still, it's definitely a sustainable vehicle — yes, that's a solar panel on the roof — and its riders would probably be crushed themselves if they ever made contact with a Ford F-150. (Found via Electrek.)

What about this wacky unicycle that tops out at 18 miles per hour, but doesn't have any pedals? It's hard to find on the internet (again, thanks, Elektrek), but we did find a YouTube video of an AIHI Body Sense Single Wheel Balancing Vehicle:

What about this golf cart-looking-thing? At 18-miles-per-hour, it's basically an electric tuk-tuk — and it's priced to move at just $818 from Alibaba. But safe in a bike lane? Check out this video:

Maybe your tastes run to "scooter death machines," as Electrek referred to this FLJ machine, whose manufacturer claims it can do 56 to 62 miles per hour.

What about this 25-mile-per-hour scrunched-up four-wheeler straight out of a Richard Scarry kids book? It's cute, right? The manufacturer, SINOTECH, calls it (sadly) a "cheap Mini electric car with high quality" — and Alibaba is selling it for around $4,000.

These examples, nearly all of which come from Electrek's "Awesomely Weird Alibaba Electric Vehicle of the Week" column, are certainly extreme, but they represent an increasingly common set of problems facing city leaders: how to sort the sprawling world of electric vehicles into regulatory categories and legislate where each of them should travel, particularly in communities where there's little space for people on non-motorized modes, never mind people in miniature low-speed electric Hummers.

That problem became particularly acute earlier this year, when it was first reported that e-bikes were outselling electric vehicles in the U.S. following a 70-percent spike in imports from the year prior. In Europe, meanwhile, e-bikes are poised to outsell gas and battery-powered cars by the end of the decade, while China, whose government has aggressively supported e-bike adoption since the early 1990s, has a staggering 300 million e-bikes on the road.

That global surge, though, has not been met with strong, globally recognized standards for what an e-bike even is — never mind an e-trike, or an e-scooter, or any of the other electric micromobility options exploding on U.S. roads right now. And without it, advocates have struggled to advocate for emerging modes that experts say could play a critical role in weaning America off car dependency — and to do so in ways that would complement non-motorized modes, rather than threaten them.

The U.S., in some ways, has been particularly slow to get its arms around the micromobility revolution — or encourage it at anywhere near the scale it deserves. Even though it was technically invented way back in 1897, there wasn't even a legal definition of an e-bike until 2002, when Congress first enshrined a muddy definition into law that encompasses both two and three-wheeled vehicles with "fully operable pedals and an electric motor of less than 750 watts," but excludes vehicles that can go more than 20 miles per hour.

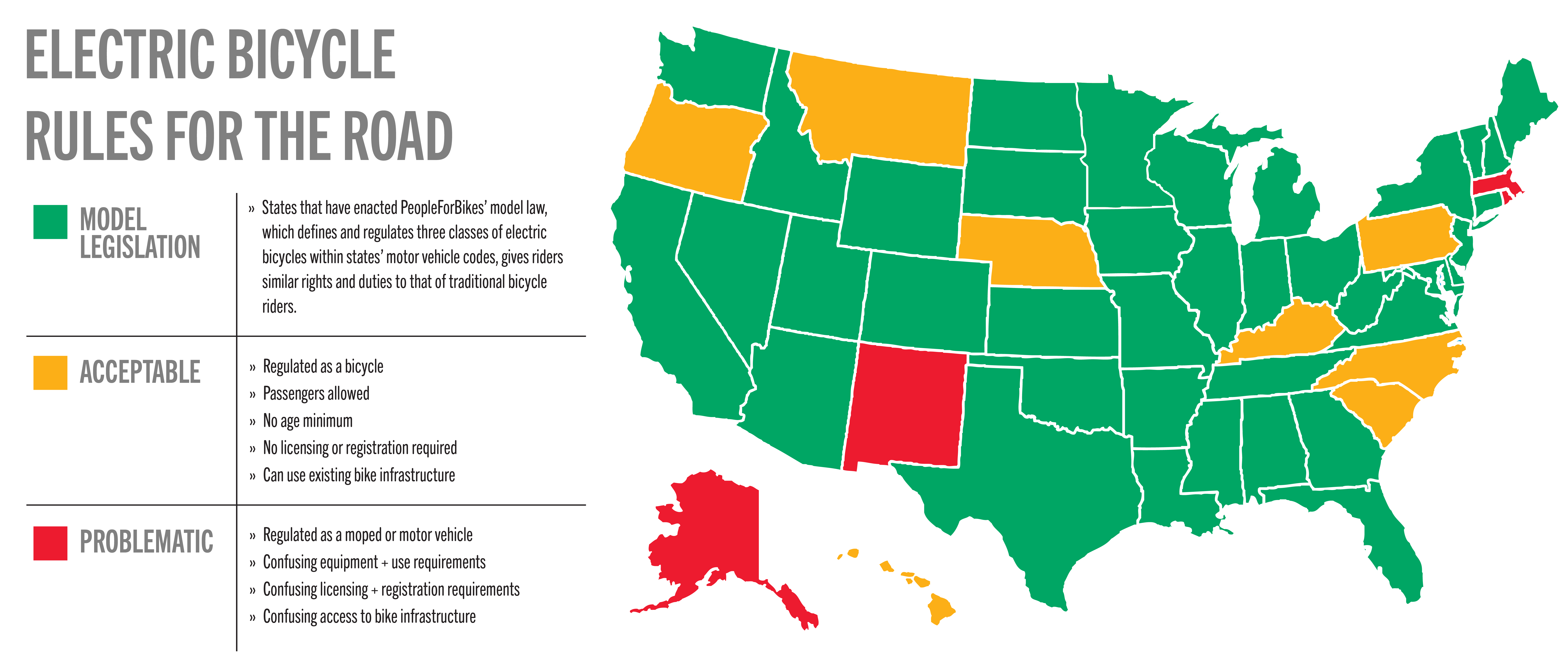

In the years since, the popular three-tiered e-bike classification system has been embraced by the bike industry and 38 states in accordance with model legislation from People for Bikes. Under that methodology, vehicles that can go up to a relatively-blistering 28 miles per hour are bikes — albeit only "class three" ones, which bars them from many bike lanes. Noa Banyan of People for Bikes adds, though, that "the majority of users are not accelerating to the motor's full potential in dense urban areas according to several studies of ridership trends," and that she typically only uses her own class three bike's higher speeds "when I'm stuck without a bike lane and trying to keep pace with cars going 20 to 25 miles per hour."

Meanwhile, neither of those definitions wholly encompasses all the micro-mobile vehicles a city would be wise to promote as an alternative to driving, particularly in their more unusual incarnations. Consider, for instance, the folding carbon-fiber YikeBike, which is solidly not a "bike" under either schema because it has no pedals, yet carries many of the same public benefits as traditional cycles, including a 15 miles per hour max speed that's relatively safe for pedestrians, an ultra-low max weight of 33 pounds, a zero-emissions battery that won't contribute to climate change, and a minuscule footprint that will never jam up a car lane.

"The human race is very creative, and we’re inventing stuff that regulatory legislative bodies aren’t keeping up with," said Ed Benjamin, chairman of the Light Electric Vehicle Association. "Sure, some of these vehicles only exist in a few hundred or a few thousand units, but a lot of them are a step in the right direction in terms of emissions and congestion. ... One of the best ways for us to get away from the internal combustion engine is to embrace vehicles that suit a person’s actual travel needs — and since so many of our trips are very short, these vehicles often fit the bill."

(Streetsblog NYC tried to capture all the different modes that it saw on the streets of the Big Apple for its first annual "Field Guide to Micro-Mobility" [PDF], but the editor there tells me the guide is already outdated!)

Whether a light electric vehicle fits a resident's needs, though, is separate from the question of whether the city has designed a place where the vehicle itself might fit — particularly when those vehicles that blur the line between traditional micromobility and micro-format electric vehicles.

Consider, for instance, the Carver cargo scooter — or, arguably more accurately, cargo moped — which would probably do some serious damage to a anyone on a bike path or sidewalk thanks to its windshield and 30 mile per hour max speed, but would be absolutely wrecked by a car, or even simply a faster motorcycle, on a roadway with a higher speed limit. Such vehicles, while still relatively rare, are already treated suspiciously by some regulators, including officials in Amsterdam, who banned "snorfiets" (which translates to "purring bicycle," or low-speed, pedalless mopeds) from entering bike lanes in 2019.

In a recent article for Micromobility Report, though, author Scott Green argued that perhaps cities should embrace mopeds, motorcycle and ultra-tiny cars as their own emerging category of "mini mobility" — even if not necessarily allowing them onto bike lanes outright. Green called the rise of even higher-speed mini-vehicles "a very positive development in the need for heightened sustainability, cleaner air and more liveable urban centres" — though he didn't offer any tips to policymakers about where such vehicles would be most safe driving on ultra-fast arterials with narrow sidewalks and no options in between, which are a common feature of American cities.

Nor did urban scholar David Zipper in a recent report from the National Safety Council, which counseled policymakers to stop writing regulations based on fuzzy form factors like "bikes," "scooters," and "cars" and start classifying vehicles by some combination of size, weight and maximum speed. Experts think those three variables can act as a rough proxy for how safe a mode is for the most vulnerable road users — and it could help regulators address the increased dangers of ever-larger pick-ups and SUVs and ever-faster mini-mobility options.

"I was just thinking about this the other day when I was walking on a [shared use path,] and over the span of about 10 minutes, two motorbikes went by," said Zipper in a recent webinar presenting the report. "These were gasoline-powered, and they were going 35, 40 miles an hour on a path withpeople teaching their children to ride a bike. It's just not safe."

Zipper acknowledged, though, that he can't predict how a city's infrastructure might be reorganized around such a classification system, calling it a "a very fruitful direction for future study." And while some communities do have dedicated lanes for mopeds motorcycles, none have yet piloted protected space for electric vehicles that are faster than a fully muscle-powered bike but slower than a Harley, never mind ones that meet more detailed safety specifications around weight, height, or front-end design.

Some experts, though, argue that the rise of hard-to-classify small electric vehicles doesn't demand that we reorganize our streetscapes to rigorously separate newly-named categories of modes. Instead, it may demand that we make all our city streets people-friendly, so that even the wildest mobility chimeras can co-exist in peace with pedestrians — and that means that megacars and mega-e-bikes will need to slow way down.

"If we give the car/truck/SUV lane a 35-mile-per-hour speed limit, we wouldn’t see the same sort of safety improvement we’d see if we lowered the speed limit to 20 mph across the whole road," said Ken McLeod, policy director for the League of American Bicyclists. "Let's just build lower speed streets, rather than fighting for inches of roadway for individual user groups. We all share the same safety concerns about large, heavy, fast vehicles — and whatever we can do to make people safer for people biking — and e-biking — will help everyone."

This story has been updated to clarify the definition of the three-tiered classification system for e-bikes, and to include additional comments from People for Bikes.